(Press-News.org) The asteroid impact 66 million years ago that ushered in a mass extinction and ended the dinosaurs also killed off many of the plants that they relied on for food. Fossil leaf assemblages from Patagonia, Argentina, suggest that vegetation in South America suffered great losses but rebounded quickly, according to an international team of researchers.

"Every mass extinction event is like a reset button, and what happens after that reset depends on which organisms survive and how they shape the biosphere," said Elena Stiles, a doctoral student at the University of Washington who completed the research as part of her master's thesis at Penn State. "All the biodiversity that we observe today is related to the organisms that made it past the last big reset 66 million years ago."

Stiles and her colleagues examined more than 3,500 leaf fossils collected at two sites in Patagonia to identify how many species from the geologic period known as the Cretaceous survived the mass extinction event into the Paleogene period. Although plant families in the region fared well, the scientists found a surprising species-level extinction rate that may have reached as high as 92% in Patagonia, higher than previous studies have estimated for the region.

"There's this idea that the Southern Hemisphere got off easier from the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction than the Northern Hemisphere because we keep finding plant and animal groups that no one thought survived," said Peter Wilf, professor of geosciences at Penn State and associate in the Earth and Environmental Systems Institute. "We went into this study expecting that Patagonia was a refuge, and instead we found a complex story of extinction and rebound."

Researchers from Penn State; the Museo Paleontologico Egidio Feruglio (MEF), Chubut, Argentina; Universidad Nacional del Comahue INIBIOMA, Rio Negro, Argentina; and Cornell University had been collecting the fossils for years from the two sites, in what is now Chubut province. Unlike North America, where the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary is well known from many sites in the western United States, the fossil record from this period is fragmented across the Southern Hemisphere, a result of rapidly changing ancient environments.

"Most of the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary interval known from the Southern Hemisphere is marine," said Ari Iglesias, a researcher at Universidad Nacional del Comahue INIBIOMA. "We were interested in obtaining the continental record, what happened on land. So, in this study we tried to get as close to the K-Pg boundary as possible, and we reached it in a small area in Chubut province. There we found floras right before the K-Pg boundary, or Maastrichtian floras, and right after the K-Pg boundary, so Danian age floras."

The assemblages that the team obtained constitute the most complete collection of late Cretaceous and early Paleogene fossil floras in the Southern Hemisphere, added Iglesias.

The researchers studied the assemblages for survivor pairs -- plants that grew in both the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods -- and found few species-level matches. They then compared their findings to previous pollen and insect herbivory studies from the same area and to North American fossil records. Their study, which is the first of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere, appears in the journal Paleobiology.

"The 92% extinction estimate we get when we consider fossil leaf species across the K-Pg boundary should be taken as a maximum" Stiles said. "We were surprised to find such high extinction levels compared with the 60% extinction rate seen in North America. Nonetheless, we observed a sharp drop in plant species diversity and a high species-level extinction."

Ecosystem recovery likely took millions of years, added Stiles, which is a small fraction of Earth's nearly 4.5-billion-year history.

Stiles also led a novel morphospace analysis to identify changes in leaf shape from the Cretaceous to the Paleogene, as such changes could provide clues to the kinds of environmental and climatic occurrences that took place across the boundary interval. She studied each leaf fossil for nearly 50 features, including shape, size and venation patterns.

The analysis showed a higher diversity of leaf forms in the Paleogene, which surprised the researchers given the high species-level extinction and drop in number of species at the end of the Cretaceous. They also found an increase in the proportion of leaf shapes typically found in cooler environments, which suggests that climatic cooling occurred after the end-Cretaceous extinction event.

The researchers' findings, combined with those of previous studies, suggest that despite the high species-level extinction at the end of the Cretaceous, South American plant families largely survived and grew more diverse during the Paleogene. Among the survivors were the laurel family, which today includes plants such as bay leaves and avocados, and the rose family, which includes fruit like raspberries and strawberries.

"Plants are often overlooked in these big events in geologic history," Stiles said. "But really, because plants are the primary producers on terrestrial landscapes and sustain all other life forms on Earth, we should be paying closer attention to the plant fossil record. It can tell us how the landscape changed and how those changes affected different groups of organisms."

INFORMATION:

Other contributors included Maria Gandolfo, Cornell University; and Ruben Cuneo, MEF.

The Geological Society of America, Mid-American Paleontological Society, National Science Foundation and Penn State, through a Charles E. Knopf, Sr. Memorial Scholarship and the Paul D. Krynine Memorial Fund, supported this research.

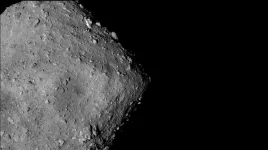

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Last month, Japan's Hayabusa2 mission brought home a cache of rocks collected from a near-Earth asteroid called Ryugu. While analysis of those returned samples is just getting underway, researchers are using data from the spacecraft's other instruments to reveal new details about the asteroid's past.

In a study published in Nature Astronomy, researchers offer an explanation for why Ryugu isn't quite as rich in water-bearing minerals as some other asteroids. The study suggests that the ancient parent body from which Ryugu was formed had likely dried out in some kind of heating event before Ryugu came into being, which left Ryugu itself drier than expected.

"One of the ...

Repeated intravenous (IV) ketamine infusions significantly reduce symptom severity in individuals with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the improvement is rapid and maintained for several weeks afterwards, according to a study conducted by researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The study, published September XX in the American Journal of Psychiatry, is the first randomized, controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic PTSD and suggests this may be a promising treatment for PTSD patients.

"Our findings provide insight into the treatment efficacy of repeated ketamine ...

As the world grows increasingly globalized, one of the ways that countries have come to rely on one another is through a more intricate and interconnected food supply chain. Food produced in one country is often consumed in another country -- with technological advances allowing food to be shipped between countries that are increasingly distant from one another.

This interconnectedness has its benefits. For instance, if the United States imports food from multiple countries and one of those countries abruptly stops exporting food to the United States, there are still other countries that can be relied on ...

SAN ANTONIO and CHICAGO - An article published Jan. 5 in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association cites decades of published scientific evidence to make a compelling case for SARS-CoV-2's expected long-term effects on the brain and nervous system.

Dementia researchers from The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio) are the first and senior authors of the report and are joined by coauthors from the Alzheimer's Association and Nottingham and Leicester universities in England.

"Since the flu pandemic of 1917 and 1918, many of the flulike diseases have been associated with brain disorders," said lead author ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Self-control, the ability to contain one's own thoughts, feelings and behaviors, and to work toward goals with a plan, is one of the personality traits that makes a child ready for school. And, it turns out, ready for life as well.

In a large study that has tracked a thousand people from birth through age 45 in New Zealand, researchers have determined that people who had higher levels of self-control as children were aging more slowly than their peers at age 45. Their bodies and brains were healthier and biologically younger.

In interviews, the higher self-control group also showed they may be better equipped to handle the health, financial and social challenges of later life as well. The researchers used structured interviews and credit checks ...

NEW YORK, NY (1/5/2021) - Subtle changes in speech and language can be an early warning sign of Alzheimer's -- sometimes appearing long before other more serious symptoms. The challenge is recognizing these changes and determining what may signal Alzheimer's or other neurodegenerative disorders. In a commentary in END ...

One sweaty, huffing, exercising person emits as many chemicals from their body as up to five sedentary people, according to a new University of Colorado Boulder study. And notably, those human emissions, including amino acids from sweat or acetone from breath, chemically combine with bleach cleaners to form new airborne chemicals with unknown impacts to indoor air quality.

"Humans are a large source of indoor emissions," said Zachary Finewax, CIRES research scientist and lead author of the new study out in the current edition of Indoor Air. "And chemicals in indoor air, whether from our bodies or cleaning products, don't just disappear, they linger and travel around spaces like gyms, reacting with other chemicals."

In 2018, the CU Boulder ...

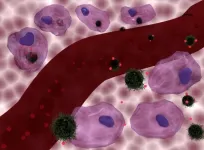

Heating up cancer cells while targeting them with chemotherapy is a highly effective way of killing them, according to a new study led by UCL researchers.

The study, published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B, found that "loading" a chemotherapy drug on to tiny magnetic particles that can heat up the cancer cells at the same time as delivering the drug to them was up to 34% more effective at destroying the cancer cells than the chemotherapy drug without added heat.

The magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles that carry the chemotherapy drug shed heat when exposed to an alternating magnetic field. This means that, once the nanoparticles have accumulated in the tumour area, an alternating magnetic field can be applied from outside the ...

Researchers in Japan have made the first observations of biological magnetoreception - live, unaltered cells responding to a magnetic field in real time. This discovery is a crucial step in understanding how animals from birds to butterflies navigate using Earth's magnetic field and addressing the question of whether weak electromagnetic fields in our environment might affect human health.

"The joyous thing about this research is to see that the relationship between the spins of two individual electrons can have a major effect on biology," said Professor Jonathan Woodward from the University of Tokyo, who conducted the research with doctoral ...

Two studies from the University of Copenhagen show that Danes aren't quite as good as Chinese at discerning bitter tastes. The research suggests that this is related to anatomical differences upon the tongues of Danish and Chinese people.

For several years, researchers have known that women are generally better than men at tasting bitter flavours. Now, research from the University of Copenhagen suggests that ethnicity may also play a role in how sensitive a person is to the bitter taste found in for example broccoli, Brussels sprouts and dark chocolate. By letting test subjects taste the bitter substance PROP, two studies demonstrate that Danish and Chinese people experience this basic taste differently. The reason seems to be related to an anatomical difference upon ...