(Press-News.org) DALLAS - Jan. 11, 2021 - A set of biomarkers not traditionally associated with cell fate can accurately predict how genetically identical cells behave differently under stress, according to a UT Southwestern study. The findings, published by Cell Reports as a Dec. 1 cover story, could eventually lead to more predictable responses to pharmaceutical treatments.

Groups of the same types of cells exposed to the same stimuli often display different responses. Some of these responses have been linked to slight differences in genetics between individual cells. However, even genetically identical cells can diverge in behavior.

One example can be found in budding yeast, or yeast that are actively dividing. When these microorganisms are deprived of glucose - the sugar molecules they use for energy - all cells stop dividing. However, when this nutrient becomes available again, some cells start dividing once more while others no longer divide but remain alive, even in batches of yeast that are genetic clones. What drives the differences in behavior between these re-dividing "quiescent" cells and never-dividing "senescent" cells has been a mystery, say study leaders N. Ezgi Wood, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at UTSW, and Mike Henne, Ph.D., assistant professor of cell biology and biophysics at UTSW.

Previous studies of behavioral differences in genetically identical cells have focused on genes that decide cell fate. However, Wood, Henne, and their colleagues took a different tact: They looked at the behavior of other biomarkers associated with basic cell maintenance, such as cell cycling, stress response, intracellular communication, and nutrient signaling.

The researchers note that the role each of these factors plays in deciding cell fate is not yet clear. Learning more about the factors that prompt cells to act differently could eventually steer researchers in new directions. For example, the knowledge could be useful in helping cells uniformly respond to cancer chemotherapies or antibiotics, areas in which cells often take divergent paths.

"How two identical cells side by side take different paths is a very basic biological question - we see it from bacteria to mammalian cells," Wood says. "Our results show that factors not traditionally associated with cell fate can, in fact, play an important role in this process, and gets us closer to answering the question of why this phenomenon takes place and how we might control it."

To explore these questions, researchers genetically modified yeast cells so that five different protein markers associated with these maintenance tasks glowed with different colors inside the cell when they were present. They then set up an experiment in which these cells lived in a microfluidics chamber that was continuously flushed with liquid media. For two hours, this media was rich with the nutrients that these cells needed to survive and multiply, including glucose. Then, for the next 10 hours, the researchers cut off the glucose supply, starving the cells. At the end of this period, they reintroduced glucose, allowing the cells to recover. During this 16-hour cycle, a camera continuously monitored individual cells, looking for differences between those that became quiescent or senescent when glucose was available again.

When they reviewed the camera footage, researchers quickly saw that despite the cells growing in an asynchronized fashion, or at different points in their cell cycles, starvation stopped the cell cycle. A closer look showed that a protein inhibitor of the cell cycle known as Whi5 tended to collect in the nuclei of quiescent cells during starvation, while Whi5 in senescent cells disappeared altogether.

Similarly, the two populations exhibited differences in the proteins Msn2 and Rtg1 that are associated with stress response. Although these proteins collected in the nuclei of all the cells when they were starved, they had a sustained presence in the nuclei of senescent cells even after glucose returned, yet largely exited the nuclei of quiescent cells when starvation ended.

The researchers found another useful marker for separating these two populations in the nucleus-vacuole junction (NVJ), an interface that connects the nucleus to the vacuole, the small digestive organelle that cells use to sequester waste products. While quiescent cells tended to enlarge their NVJs during starvation, senescent cells did not.

Although each of these findings gave clues to which path cells would take after starvation started, none showed any predictive powers before starvation took place. But when the researchers examined Rim15, a protein that plays a key role in nutrient signaling, they found that cells with elevated Rim15 before starvation tended to become quiescent while those with lower concentrations of this protein were more likely to become senescent.

On their own, none of these factors served as an accurate predictor of cell fate. But when Wood, Henne, and their colleagues performed a statistical analysis incorporating all of them, they were able to accurately predict which cells became quiescent and which became senescent with an accuracy of nearly 90 percent before they reintroduced glucose. In fact, they say, cells seem to reach a "decision point" where it's unlikely that they'll change their direction about four hours into starvation.

INFORMATION:

Other UTSW researchers who contributed to this study include Piya Kositangool, Hanaa Hariri, and Ashley J. Marchand. Henne is a W.W. Caruth, Jr. Scholar in Biomedical Research and a member of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center.

This research was funded by grants from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR150058), The Welch Foundation (I-1873), National Institutes of Health NIGMS (GM119768), the Ara Parseghian Fund (APMRF2020), and UTSW Endowed Scholars Program.

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution's faculty has received six Nobel Prizes, and includes 23 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 17 members of the National Academy of Medicine, and 13 Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigators. The full-time faculty of more than 2,500 is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide care in about 80 specialties to more than 105,000 hospitalized patients, nearly 370,000 emergency room cases, and oversee approximately 3 million outpatient visits a year.

As the planet continues to warm, the twin challenges of diminishing water supply and growing energy demand are intensifying. But because water and energy are inextricably linked, as we try to adapt to one challenge - say, by getting more water via desalination or water recycling - we may be worsening the other challenge by choosing energy-intensive processes.

So, in adapting to the consequences of climate change, how can we be sure that we aren't making problems worse?

Now, researchers at the Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), UC Berkeley, and UC Santa Barbara have developed a science-based analytic framework to evaluate such complex connections between water and energy, and options for adaptations in response to an evolving ...

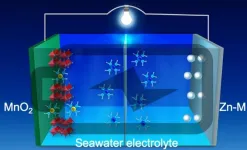

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Researchers in the Oregon State University College of Engineering have developed a battery anode based on a new nanostructured alloy that could revolutionize the way energy storage devices are designed and manufactured.

The zinc- and manganese-based alloy further opens the door to replacing solvents commonly used in battery electrolytes with something much safer and inexpensive, as well as abundant: seawater.

Findings were published today in Nature Communications.

"The world's energy needs are increasing, but the development of next-generation electrochemical energy storage systems with high energy density and long cycling life ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - Biomarkers in human sperm have been identified that can indicate a propensity to father children with autism spectrum disorder. These biomarkers are epigenetic, meaning they involve changes to molecular factors that regulate genome activity such as gene expression independent of DNA sequence, and can be passed down to future generations.

In a study published in the journal Clinical Epigenetics on Jan. 7, researchers identified a set of genomic features, called DNA methylation regions, in sperm samples from men who were known to have autistic children. Then in a set of blind tests, the researchers were able to use the presence of these features to determine whether other men had fathered autistic children with 90% ...

New research shows people who pursue meaningful activities - things they enjoy doing - during lockdown feel more satisfied than those who simply keep themselves busy.

The study, published in PLOS ONE, shows you're better off doing what you love and adapting it to suit social distancing, like swapping your regular morning walk with friends for a zoom exercise session.

Simply increasing your level of activity by doing mindless busywork will leave you unsettled and unsatisfied.

Co-lead researcher Dr Lauren Saling from RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia said while novelty lockdown activities - like baking or painting - have their place, trying to continue what you enjoyed before lockdown can be more rewarding.

"Busyness might be distracting but it won't necessarily be fulfilling," ...

COVID-19 infections are once again rising at an alarming rate in San Francisco's Latinx community, predominantly among low-income essential workers, according to results of a massive community-based testing blitz conducted before and after the Thanksgiving holiday by Unidos En Salud -- a volunteer-led partnership between the Latino Task Force for COVID-19 (LTF), UC San Francisco , the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub (CZ Biohub), and the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH).

Unidos En Salud launched their "Healthy Holidays" initiative the weekend before Thanksgiving (Nov. 22-24) in San Francisco's Mission District, where they have been perfecting their community-based surveillance testing ...

The genetic material of plants, animals and humans is well protected in the nucleus of each cell and stores all the information that forms an organism. For example, information about the size or color of flowers, hair or fur is predefined here. In addition, cells contain small organelles that contain their own genetic material. These include chloroplasts in plants, which play a key role in photosynthesis, and mitochondria, which are found in all living organisms and represent the power plants of every cell. But is the genetic material actually permanently stored within one cell? No! As so far known, the genetic material can migrate from cell to cell and thus even be exchanged between different organisms. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology (MPI-MP) ...

We are fascinated by machines that can control cars, compose symphonies, or defeat people at chess, Go, or Jeopardy! While more progress is being made all the time in Artificial Intelligence (AI), some scientists and philosophers warn of the dangers of an uncontrollable superintelligent AI. Using theoretical calculations, an international team of researchers, including scientists from the Center for Humans and Machines at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, shows that it would not be possible to control a superintelligent AI. The study was published in the Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research.

Suppose someone ...

When an accident occurs, the reactions of bystanders are important. Researchers have studied whether laypeople realise the severity of the situation when someone in their proximity begins to bleed, and whether they can estimate how much the person is bleeding. The results show a discrepancy related to the victim's gender: for a woman losing blood, both blood loss and life-threatening injuries were underestimated. The study has been published in the scientific journal PLoS One.

Researchers from Linköping University and Old Dominion University in the United States wanted to study the ability of laypeople to visually assess blood loss, and what influences them when judging the severity of an injury.

"Laypeople's ...

Recent years have provided substantial research displaying the effect of genetic mu-tations on the development of autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Based on those studies, researchers have focused attention on the commonalities be-hind those mutations and how they impact on the functioning of the brain. A study conducted by Professor Sagiv Shifman from the Life Sciences Institute at the He-brew University of Jerusalem and the Center for Autism Research has found that genes associated with autism tend to be involved in the regulation of other genes and to operate preferentially in three areas of the brain; the cortex, the striatum, and the cerebellum.

The cerebellum ...

Rice is the staple food of about half the world's population. The cultivation of the rice plant is very water-intensive and, according to the German aid organization Welthungerhilfe, around 15 per cent of rice is grown in areas with a high risk of drought. Global warming is therefore becoming increasingly problematic for rice cultivation, leading more and more often to small harvests and hunger crises. Crop failures caused by plant pathogens further aggravate the situation. Here, conventional agriculture is trying to counteract this with pesticides, which are mostly used as a precautionary measure in rice cultivation. The breeding of resistant plants is the only alternative to these environmentally harmful ...