(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - An unfortunate truth about the use of mechanical ventilation to save the lives of patients in respiratory distress is that the pressure used to inflate the lungs is likely to cause further lung damage.

In a new study, scientists identified a molecule that is produced by immune cells during mechanical ventilation to try to decrease inflammation, but isn't able to completely prevent ventilator-induced injury to the lungs.

The team is working on exploiting that natural process in pursuit of a therapy that could lower the chances for lung damage in patients on ventilators. Delivering high levels of the helpful molecule with a nanoparticle was effective at fending off ventilator-related lung damage in mice on mechanical ventilation.

"Our data suggest that the lungs know they're not supposed to be overinflated in this way, and the immune system does its best to try to fix it, but unfortunately it's not enough," said Dr. Joshua A. Englert, assistant professor of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and co-lead author of the study. "How can we exploit this response and take what nature has done and augment that? That led to the therapeutic aims in this study."

The work builds upon findings from the lab of co-lead author Samir Ghadiali, professor and chair of biomedical engineering at Ohio State, who for years has studied how the physical force generated during mechanical ventilation activates inflammatory signaling and causes lung injury.

Efforts in other labs to engineer ventilation systems that could reduce harm to the lungs haven't panned out, Ghadiali said.

"We haven't found ways to ventilate patients in a clinical setting that completely eliminates the injurious mechanical forces," he said. "The alternative is to use a drug that reduces the injury and inflammation caused by mechanical stresses."

The research is published today (Jan. 12, 2021) in Nature Communications.

Though a therapy for humans is years away, the progress comes at a time when more patients than ever before are requiring mechanical ventilation: Cases of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have skyrocketed because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. ARDS is one of the most frequent causes of respiratory failure that leads to putting patients on a ventilator.

"Before COVID, there were several hundred thousand cases of ARDS in the United States each year, most of which required mechanical ventilation. But in the past year there have been 21 million COVID-19 patients at risk," said Englert, a physician who treats ICU patients.

The immune response to ventilation and the inflammation that comes with it can add to fluid build-up and low oxygen levels in the lungs of patients already so sick that they require life support.

The molecule that lessens inflammation in response to mechanical ventilation is called microRNA-146a (miR-146a). MicroRNAs are small segments of RNA that inhibit genes' protein-building functions - in this case, turning off the production of proteins that promote inflammation.

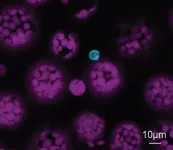

The researchers found that immune cells in the lungs called alveolar macrophages - whose job is to protect the lungs from infection - activate miR-146a when they're exposed to pressure that mimics mechanical ventilation. This action makes miR-146a part of the innate, or immediate, immune response launched by the body to begin its fight against what it is perceiving as an infection - the mechanical ventilation.

"This means an innate regulator of the immune system is activated by mechanical stress. That makes me think it's there for a reason," Ghadiali said. That reason, he said, is to help calm the inflammatory nature of the very immune response that is producing the microRNA.

The research team confirmed the moderate increase of miR-146a levels in alveolar macrophages in a series of tests on cells from donor lungs that were exposed to mechanical pressure and in mice on miniature ventilators. The lungs of genetically modified mice that lacked the microRNA were more heavily damaged by ventilation than lungs in normal mice - pointing to miR-146a's protective role in lungs during mechanical breathing assistance. Finally, the researchers examined cells from lung fluid of ICU patients on ventilators and found miR-146a levels in their immune cells were increased as well.

The problem: The expression of miR-146a under normal circumstances isn't high enough to stop lung damage from prolonged ventilation.

The intended therapy would be introducing much higher levels of miR-146a directly to the lungs to ward off inflammation that can lead to injury. When overexpression of miR-146a was prompted in cells that were then exposed to mechanical stress, inflammation was reduced.

To test the treatment in mice on ventilators, the team delivered nanoparticles containing miR-146a directly to mouse lungs - which resulted in a 10,000-fold increase in the molecule that reduced inflammation and kept oxygen levels normal. In the lungs of ventilated mice that received "placebo" nanoparticles, the increase in miR-146a was modest and offered little protection.

From here, the team is testing the effects of manipulating miR-146a levels in other cell types - these functions can differ dramatically, depending on each cell type's job.

"In my mind, the next step is demonstrating how to use this technology as a precision tool to target the cells that need it the most," Ghadiali said.

INFORMATION:

The collaborative work by researchers in engineering, pulmonary medicine and drug delivery was conducted at Ohio State's Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute (DHLRI), where Englert and Ghadiali have labs and teamed with Ohio State graduate students and co-first authors Christopher Bobba from the MD/PhD training program and Qinqin Fei from the College of Pharmacy to lead the studies.

Additional Ohio State co-authors include DHLRI investigators Vasudha Shukla, Hyunwook Lee, Pragi Patel, Mark Wewers, John Christman and Megan Ballinger; Carleen Spitzer and MuChun Tsai of the College of Medicine; and Robert Lee of the College of Pharmacy. Rachel Putman of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston also worked on the study.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense, and an Ohio State Presidential Fellowship.

Contacts:

Joshua Englert, Joshua.Englert@osumc.edu

Samir Ghadiali, Ghadiali.1@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, Caldwell.151@osu.edu

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, January 12, 2020: New research from NYU Abu Dhabi's Laboratory of Neural Systems and Behavior for the first time used an animal model to demonstrate how abnormal sleep architecture can be a predictor of stress vulnerability. These important findings have the potential to inform the development of sleep tests that can help identify who may be susceptible -- or resilient -- to future stress.

In the study, Abnormal Sleep Signals Vulnerability to Chronic Social Defeat Stress, which appears in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience, NYUAD Assistant Professor of Biology Dipesh Chaudhury and Research Associate Basma Radwan describe their development of a mouse ...

ORLANDO, Fla. -- A new national survey by the Orlando Health Heart & Vascular Institute finds many Americans would delay doctor's appointments and even emergency care when COVID-19 rates are high. The survey found 67 percent of Americans are more concerned about going to medical appointments when COVID-19 rates are high in their area and nearly three in five (57 percent) are hesitant to go to the hospital even for an emergency.

In a time when every trip out of the house and every person we come in contact with poses a threat of contracting COVID-19, ...

WASHINGTON - Computer-based artificial intelligence can function more like human intelligence when programmed to use a much faster technique for learning new objects, say two neuroscientists who designed such a model that was designed to mirror human visual learning.

In the journal Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, Maximilian Riesenhuber, PhD, professor of neuroscience, at Georgetown University Medical Center, and Joshua Rule, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar at UC Berkeley, explain how the new approach vastly improves the ability of AI software to quickly learn new visual ...

The Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) has announced that the research team led by Dr. Kim Kyoung-Whan at the Center for Spintronics has proposed a new principle about spin memory devices, which are next-generation memory devices. This breakthrough presents new applicability that is different from the existing paradigm.

Conventional memory devices are classified into volatile memories, such as RAM, that can read and write data quickly, and non-volatile memories, such as hard-disk, on which data are maintained even when the power is off. In recent years, related academic and industrial fields have been combining their advantages to accelerate the development of next-generation memory that is fast and capable of maintaining data even when the power is off.

A spin memory ...

The leaf vasculature of plants plays a key role in transporting solutes from where they are made - for example from the plant cells driving photosynthesis - to where they are stored or used. Sugars and amino acids are transported from the leaves to the roots and the seeds via the conductive pathways of the phloem.

Phloem is the part of the tissue in vascular plants that comprises the sieve elements - where actual translocation takes place - and the companion cells as well as the phloem parenchyma cells. The leaf veins consist of at least seven distinct cell types, with specific roles in transport, metabolism and signalling.

Little is known about ...

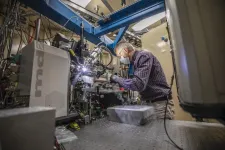

A team of HIV researchers, cellular biologists, and biophysicists who banded together to support COVID-19 science determined the atomic structure of a coronavirus protein thought to help the pathogen evade and dampen response from human immune cells. The structural map - which is now published in the journal PNAS, but has been open-access for the scientific community since August - has laid the groundwork for new antiviral treatments tailored specifically to SARS-CoV-2, and enabled further investigations into how the newly emerged virus ravages the human body.

"Using X-ray crystallography, we built an ...

A new study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found a 25% increase in food insufficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Food insufficiency, the most extreme form of food insecurity, occurs when families do not have enough food to eat. Among the nationally representative sample of 63,674 adults in the US, Black and Latino Americans had over twice the risk of food insufficiency compared to White Americans.

"People of color are disproportionately affected by both food insufficiency and COVID-19," said Jason Nagata, MD, MSc, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco and lead author on the study. "Many of these individuals have experienced job loss and higher rates of poverty during the ...

During April 2020, while the UK was in full lockdown, there was a drop of more than a third in the number of people seeking help for mental illness or self-harm according to research involving 14 million people registered at general practices across the four nations of the UK which was published today in The Lancet Public Health*.

The research, 'Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care-recorded mental illness and self-harm episodes in the UK: a population-based cohort study', was conducted by the National Institute for Health Research Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre (NIHR GM PSTRC). The Centre is a partnership between The University of Manchester and Salford Royal NHS Foundation ...

In a surprising discovery, Princeton physicists have observed an unexpected quantum behavior in an insulator made from a material called tungsten ditelluride. This phenomenon, known as quantum oscillation, is typically observed in metals rather than insulators, and its discovery offers new insights into our understanding of the quantum world. The findings also hint at the existence of an entirely new type of quantum particle.

The discovery challenges a long-held distinction between metals and insulators, because in the established quantum theory of materials, insulators were not thought to be able to ...

Reston, Virginia--Physicians who follow artificial intelligence (AI) advice may be considered less liable for medical malpractice than is commonly thought, according to a new study of potential jury candidates in the U.S. Published in the January issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine (JNM). The study provides the first data related to physicians' potential liability for using AI in personalized medicine, which can often deviate from standard care.

"New AI tools can assist physicians in treatment recommendations and diagnostics, including the interpretation of medical images," remarked Kevin Tobia, JD, PhD, ...