(Press-News.org) When the Thomas Fire raged through Ventura and Santa Barbara counties in December 2017, Danielle Touma, at the time an earth science researcher at Stanford, was stunned by its severity. Burning for more than a month and scorching 440 square miles, the fire was then considered the worst in California's history.

Six months later the Mendocino Complex Fire upended that record and took out 717 square miles over three months. Record-setting California wildfires have since been the norm, with five of the top 10 occurring in 2020 alone.

The disturbing trend sparked some questions for Touma, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at UC Santa Barbara's Bren School for Environmental Science & Management.

"Climate scientists knew that there was a climate signal in there but we really didn't understand the details of it," she said of the transition to a climate more ideal for wildfires. While research has long concluded that anthropogenic activity and its products -- including greenhouse gas emissions, biomass burning, industrial aerosols (a.k.a. air pollution) and land-use changes -- raise the risk of extreme fire weather, the specific roles and influences of these activities was still unclear.

Until now. In the first study of its kind, Touma, with fellow Bren School researcher Samantha Stevenson and colleagues Flavio Lehner of Cornell University and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), and Sloan Coats from the University of Hawaii, have quantified competing anthropogenic influences on extreme fire weather risk in the recent past and into the near future. By disentangling the effects of those man-made factors the researchers were able to tease out the roles these activities have had in generating an increasingly fire-friendly climate around the world and the risk of extreme fire weather in decades to come.

Their work appears in the journal Nature Communications.

"By understanding the different pieces that go into these scenarios of future climate change, we can get a better sense of what the risks associated with each of those pieces might be, because we know there are going to be uncertainties in the future," Stevenson said. "And we know those risks are going to be expressed unequally in different places too, so we can be better prepared for which parts of the world might be more vulnerable."

Warm, Dry and Windy

"To get a wildfire to ignite and spread, you need suitable weather conditions -- you need warm, dry and windy conditions," Touma said. "And when these conditions are at their most extreme, they can cause really large, severe fires."

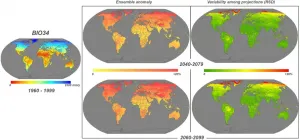

Using state-of-the-art climate model simulations available from NCAR, the researchers analyzed the climate under various combinations of climate influences from 1920-2100, allowing them to isolate individual effects and their impacts on extreme fire weather risk.

According to the study, heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions (which started to increase rapidly by mid-century) are the dominant contributor to temperature increases around the globe. By 2005, emissions raised the risk of extreme fire weather by 20% from preindustrial levels in western and eastern North America, the Mediterranean, Southeast Asia and the Amazon. The researchers predict that by 2080, greenhouse gas emissions are expected to raise the risk of extreme wildfire by at least 50% in western North America, equatorial Africa, Southeast Asia and Australia, while doubling it in the Mediterranean, southern Africa, eastern North America and the Amazon.

Meanwhile, biomass burning and land-use changes have more regional impacts that amplify greenhouse gas-driven warming, according to the study -- notably a 30% increase of extreme fire weather risk over the Amazon and western north America during the 20th century caused by biomass burning. Land use changes, the study found, also amplified the likelihood of extreme fire weather in western Australia and the Amazon.

Protected by Pollution?

The role of industrial aerosols has been more complex in the 20th century, actually reducing the risk of extreme fire weather by approximately 30% in the Amazon and Mediterranean, but amplifying it by at least 10% in southeast Asia and Western North America, the researchers found.

"(Industrial aerosols) block some of the solar radiation from reaching the ground," Stevenson said. "So they tend to have a cooling effect on the climate.

"And that's part of the reason why we wanted to do this study," she continued. "We knew something had been compensating in a sense for greenhouse gas warming, but not the details of how that compensation might continue in the future."

The cooling effect may still be present in regions such as the Horn of Africa, Central America and the northeast Amazon, where aerosols have not been reduced to pre-industrial levels. Aerosols may still compete with greenhouse gas warming effects in the Mediterranean, western North America and parts of the Amazon, but the researchers expect this effect to dissipate over most of the globe by 2080, due to cleanup efforts and increased greenhouse gas-driven warming. Eastern North America and Europe are likely to see the warming and drying due to aerosol reduction first.

Southeast Asia meanwhile, "where aerosols emissions are expected to continue," may see a weakening of the annual monsoon, drier conditions and an increase in extreme fire weather. risk.

"Southeast Asia relies on the monsoon, but aerosols cause so much cooling on land that it actually can suppress a monsoon," Touma said. "It's not just whether you have aerosols or not, it's the way the regional climate interacts with aerosols."

The researchers hope that the detailed perspective offered by their study opens the door to more nuanced explorations of the Earth's changing climate.

"In the broader scope of things, it's important for climate policy, like if we want to know how global actions will affect the climate," Touma said. "And it's also important for understanding the potential impacts to people, such as with urban planning and fire management."

INFORMATION:

DARIEN, IL - Editors of the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine have identified some of the most significant articles in the publication's history, publishing new commentaries on them in a special 15th anniversary collection. The 15 commentaries from associate editors and members of the journal's editorial board describe the impact of the selected articles both at the time of their publication and today.

"The collection highlights some of the most influential publications in clinical sleep research over the past 15 years," JCSM Editor-in-Chief Dr. Nany Collop said. "These studies underscore the remarkable ...

By feeding arctic ground squirrels special diets, researchers have found that omega-3 fatty acids, common in flax seed and fish oil, help keep the animals warmer in deep hibernation.

A University of Alaska Fairbanks-led study fed ground squirrels either a diet high in omega-3s or a normal laboratory diet, and measured how the animals hibernated afterward. Researchers found that the omega-3 diet helped the animals hibernate a little warmer than normal without negatively affecting hibernation. The omega-3 diets also increased the amount of a heat-producing fat, called brown adipose tissue, the animals pack on.

The discovery could add more understanding ...

DURHAM, N.H.-- Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), a rare form of lymphoma, does not have any known cure and only one FDA-approved treatment making it challenging to treat patients. Researchers at the University of New Hampshire took the novel approach of targeting specific cell proteins that control DNA information using inhibitors, or drugs, that were effective in reducing the growth of the cancer cells and when combined with a third drug were even more successful in killing the WM cancer cells which could lead to more treatment options.

"This is the first study to report the promising results ...

Astronomers are winding back the clock on the expanding remains of a nearby, exploded star. By using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, they retraced the speedy shrapnel from the blast to calculate a more accurate estimate of the location and time of the stellar detonation.

The victim is a star that exploded long ago in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to our Milky Way. The doomed star left behind an expanding, gaseous corpse, a supernova remnant named 1E 0102.2-7219, which NASA's Einstein Observatory first discovered in X-rays. Like detectives, researchers sifted through archival images taken by Hubble, analyzing visible-light observations made 10 years apart.

The research team, led by John Banovetz and Danny Milisavljevic ...

In addition to a skin rash, many eczema sufferers also experience chronic itching, but sometimes that itching can become torturous. Worse, antihistamines -- the standard treatment for itching and allergy -- often don't help.

New research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that allergens in the environment often are to blame for episodes of acute itch in eczema patients, and that the itching often doesn't respond to antihistamines because the itch signals are being carried to the brain along a previously unrecognized pathway that current drugs don't target.

The new findings, published ...

The sun is the only star in our system. But many of the points of light in our night sky are not as lonely. By some estimates, more than three-quarters of all stars exist as binaries -- with one companion -- or in even more complex relationships. Stars in close quarters can have dramatic impacts on their neighbors. They can strip material from one another, merge or twist each other's movements through the cosmos.

And sometimes those changes unfold over the course of a few generations.

That is what a team of astronomers from the University of Washington, Western Washington University and the University ...

There's a 7-fold unexplained variation in rates of euthanasia across The Netherlands, reveals an analysis of health insurance claims data, published online in the journal BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care.

It's not clear if these differences relate to underuse, overuse, or even misuse, say the researchers.

The Netherlands was the first country in the world to legalise euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, introducing preliminary legislation in 1994, followed by a fully fledged law in 2002. The practice has been tolerated, however, since 1985.

Official data show that the number of euthanasia cases has risen more or less continuously since 2006, reaching 6361 in 2019. These cases ...

Climate change impacts, affecting primarily ecosystems' functions and consequently human sectors, have become a crucial topic. Observed and expected variations in climate conditions can in fact undermine the ecosystems' ecological equilibrium: average climate patterns, mainly represented by intra-annual (monthly to seasonal) temperature and precipitation cycle, directly influence the distribution, abundance and interactions of biological species.

During the long history of scientific research on the relationships between climate and Earth's communities, ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Use of the diabetes drug metformin -- before a diagnosis of COVID-19 -- is associated with a threefold decrease in mortality in COVID-19 patients with Type 2 diabetes, according to a racially diverse study at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Diabetes is a significant comorbidity for COVID-19.

"This beneficial effect remained, even after correcting for age, sex, race, obesity, and hypertension or chronic kidney disease and heart failure," said Anath Shalev, M.D., director of UAB's Comprehensive Diabetes Center and leader of the study.

"Since similar results have now been obtained in different populations from around the world -- including China, France and a UnitedHealthcare analysis -- this suggests that the ...

Ignoring a colleague's greeting or making a sarcastic comment in the workplace may actually do more harm than intended, according to West Virginia University research.

Perceived low-grade forms of workplace mistreatment, such as avoiding eye contact or excluding a coworker from conversation, can amplify suicidal thoughts in employees with mood disorders, based on a study by Kayla Follmer, assistant professor of management, and Jake Follmer, assistant professor of educational psychology.

"We know from prior research that minor forms of workplace mistreatment reduce employee engagement," Kayla Follmer said. "But our paper provided an explanation for ...