INFORMATION:

Memory fail controlled by dopamine circuit, study finds

'Transient forgetting' mechanism revealed; pauses thought without abolishing long-term memories

2021-01-21

(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL - In a landmark neurobiology study, scientists from Scripps Research have discovered a memory gating system that employs the neurotransmitter dopamine to direct transient forgetting, a temporary lapse of memory which spontaneously returns.

The study adds a new pin to scientists' evolving map of how learning, memory and active forgetting work, says Scripps Research Neuroscience Professor Ron Davis, PhD.

"This is the first time a mechanism has been discovered for transient memory lapse," Davis says. "There's every reason to believe, because of conservation biology, that a similar mechanism exists in humans as well."

The study, "Dopamine-based mechanism for transient forgetting," appears Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Everyone has experienced transient forgetting. A name sits on the tip of our tongue, but resurfaces only after a meeting. We walk into a room and forget why we entered - until we leave. Annoying, to be sure. But does it represent a mental glitch, or is absentmindedness a feature of a normal brain? Was the elusive memory erased and somehow restored, or merely hidden for a time? Exactly how transient forgetting worked was unknown until now.

To derive an answer, Davis' team worked in the common fruit fly, a model favored by neurobiologists for decades due to its relatively simple brain structure, ease of study and translatability to more complex animals.

The team put their flies through a series of training exercises, teaching them to associate an odor with an unpleasant foot shock. They then watched as several interfering stimuli, such as a blue light or a puff of air, distracted the flies so they forgot the odor's negative association, temporarily. Interestingly, stronger stimulation led to longer lasting periods of forgetting.

Additional biochemical studies revealed a single pair of dopamine-releasing neurons in the flies, called PPL1-α2α'2, which directed the transient forgetting. Dopamine sent from other neurons didn't have the same effect. The neurons activated dopamine receptors called DAMB on axons extending from neurons in the memory-processing center of the fruit fly brain, called its mushroom body.

Activation of the transient forgetting circuit did not erase the flies' long-term memory recall, suggesting that transient forgetting doesn't affect permanent, consolidated memory traces, or engrams, that are acquired over time, Davis says.

Intriguingly, they found the flies' memory performance was restored after the transient forgetting period lifted, says the paper's first author, John Martin Sabandal, a Scripps Research graduate student, who worked with staff scientist Jacob Berry, PhD, at the team's lab in Jupiter, Florida.

"Could we perform better if certain memories are suppressed over others - could we learn or adapt to situations better? Nobody knows. Those are the type of questions that will be explored in the future," Sabandal says. "We found, provisionally, there is a potential memory reserve that is just unable to be expressed at a particular moment."

The mechanisms underlying long-term memory acquisition and consolidation have been thoroughly studied over the past 40 years, Davis says, but forgetting has been overlooked until recently. It's proving to be a fascinating field. In 2012 Davis' group found a mechanism directing permanent forgetting, finding it is an ongoing, active process, one apparently needed for healthy brain function.

"You can imagine that we have thousands of memories that occur every day in our lifetime, and the brain does not have the capability of remembering, or encoding, all of those memories. So there is a need to erase those memories that are irrelevant to our existence and our daily lives," Davis says.

Taken together, it's increasingly clear that much of what we think of as memory loss is not a result of broken connections or age-related decline, but an important feature, one necessary for survival, Davis says. Much more work lies ahead, he adds.

"We now know that there is a specific receptor in the memory center that receives the transient forgetting signal from dopamine. But we don't yet know what happens downstream. What does that receptor do to the physiology of the neuron that temporarily blocks memory retrieval? That's the major next goal, to understand how this block in retrieval occurs through the activation of this dopamine receptor," Davis says. "We are just at the very beginning of understanding how the brain causes transient forgetting."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The idea of an environmental tax is finally gaining strength

2021-01-21

An extra 290,000 pounds a year for lighting and cleaning because smog darkens and pollutes everything: with this cost estimate for the industrial city of Manchester, the English economist Arthur Cecil Pigou once founded the theory of environmental taxation. In the classic "The Economics of Welfare", the first edition of which was published as early as 1920, he proved that by allowing such "externalities" to flow into product prices, the state can maximise welfare. In 2020, exactly 100 years later, the political implementation of Pigou's insight has gained strength, important objections are being invalidated, and carbon pricing appears more efficient than regulations and bans according to a ...

Antarctica: the ocean cools at the surface but warms up at depth

2021-01-21

Scientists from the CNRS, CNES, IRD, Sorbonne Université, l'Université Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier and their Australian colleagues*, with the support of the IPEV, have provided a comprehensive analysis on the evolution of Southern Ocean temperatures over the last 25 years. The research team has concluded that the slight cooling observed at the surface hides a rapid and marked warming of the waters, to a depth of up to 800 metres. The study points to major changes around the polar ice cap where temperatures are increasing by 0.04°C per decade, which could have serious consequences for Antarctic ice. Warm water is also rising rapidly to the surface, at a rate of 39 metres per decade, i.e. between three and ten ...

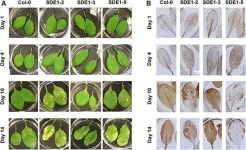

Novel effector biology research provides insights into devastating citrus greening disease

2021-01-21

Citrus greening disease, also known as Huanglongbing (HLB), is devastating to the citrus industry, causing unprecedented amounts of damage worldwide. There is no known cure. Since the disease's introduction to the United States in the early 2000s, research efforts have increased exponentially. However, there is still a lack of information about the molecular mechanism behind the disease.

"Getting into the molecular details behind what contributes to citrus greening symptom development and disease progression is key to finding sustainable solutions to combat the pathogen," explained plant pathologist Wenbo Ma. "We bring the community one step closer to understanding these mechanisms ...

Feral colonies provide clues for enhancing honey bee tolerance to pathogens

2021-01-21

Understanding the genetic and environmental factors that enable some feral honey bee colonies to tolerate pathogens and survive the winter in the absence of beekeeping management may help lead to breeding stocks that would enhance survival of managed colonies, according to a study led by researchers in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences.

Feralization occurs when previously domesticated organisms escape to the wild and establish populations in the absence of human influence, explained lead researcher Chauncy Hinshaw, doctoral candidate in plant pathology and environmental microbiology.

"In the case of honey bees, colonies that escape domestication and establish in the wild provide an opportunity to study how environmental and genetic factors ...

Well-built muscles underlie athletic performance in birds

2021-01-21

Muscle structure and body size predict the athletic performance of Olympic athletes, such as sprinters. The same, it appears, is true of wild seabirds that can commute hundreds of kilometres a day to find food, according to a recent paper by scientists from McGill and Colgate universities published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

The researchers studied a colony of small gulls, known as black-legged kittiwakes, that breed and nest in an abandoned radar tower on Middleton Island, Alaska. They attached GPS-accelerometers--Fitbit for birds -- ...

As oceans warm, large fish struggle

2021-01-21

Warming ocean waters could reduce the ability of fish, especially large ones, to extract the oxygen they need from their environment. Animals require oxygen to generate energy for movement, growth and reproduction. In a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, an international team of researchers from McGill, Montana and Radboud universities describe their newly developed model to determine how water temperature, oxygen availability, body size and activity affect metabolic demand for oxygen in fish.

The model is based on physicochemical principles that look at oxygen consumption and diffusion at the gill surface in relation to water temperature and body size. Predictions were compared against actual measurements from over 200 fish species where oxygen ...

Discovery of new praying mantis species from the time of the dinosaurs

2021-01-21

A McGill-led research team has identified a new species of praying mantis thanks to imprints of its fossilized wings. It lived in Labrador, in the Canadian Subarctic around 100 million years ago, during the time of the dinosaurs, in the Late Cretaceous period. The researchers believe that the fossils of the new genus and species, Labradormantis guilbaulti, helps to establish evolutionary relationships between previously known species and advances the scientific understanding of the evolution of the most 'primitive' modern praying mantises. The unusual find, described in a recently published study in Systematic ...

Methane emissions from abandoned oil and gas wells underestimated

2021-01-21

A recent McGill study published in Environmental Science and Technology finds that annual methane emissions from abandoned oil and gas (AOG) wells in Canada and the US have been greatly underestimated - by as much as 150% in Canada, and by 20% in the US. Indeed, the research suggests that methane gas emissions from AOG wells are currently the 10th and 11th largest sources of anthropogenic methane emission in the US and Canada, respectively. Since methane gas is a more important contributor to global warming than carbon dioxide, especially over the short term, the researchers believe that it is essential to gain a clearer understanding of methane ...

Scientists discover link between nicotine and breast cancer metastasis

2021-01-21

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - Jan. 20, 2021 - Breast cancer is the second most common cancer among women in the United States, and cigarette smoking is associated with a higher incidence of breast cancer spread, or metastasis, lowering the survival rate by 33% at diagnosis.

While cigarette smoking's link to cancer is well-known, the role of nicotine, a non-carcinogenic chemical found in tobacco, in breast-to-lung metastasis is an area where more research is needed.

Now, scientists at Wake Forest School of Medicine have found that nicotine promotes the spread of breast cancer cells into the lungs.

The study ...

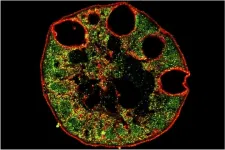

For some, GI tract may be vulnerable to COVID-19 infection

2021-01-21

No evidence so far indicates that food or drinks can transmit the virus that causes COVID-19, but new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that people with problems in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract may be vulnerable to infection after swallowing the virus.

Studying tissue from patients with a common disorder called Barrett's esophagus, the researchers found that although cells in a healthy esophagus cannot bind to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, esophageal cells from patients with Barrett's have receptors for the virus, and those cells can bind to and become infected by the virus that causes COVID-19.

The study is published online Jan. 20 in the journal Gastroenterology.

"There ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

[Press-News.org] Memory fail controlled by dopamine circuit, study finds'Transient forgetting' mechanism revealed; pauses thought without abolishing long-term memories