Beetles reveal how to hide the body

2021-01-21

(Press-News.org) Not long after the sun goes down, pairs of burying beetles, or Nicrophorus orbicollis, begin looking for corpses.

For these beetles, this is not some macabre activity; it's house-hunting, and they are in search of the perfect corpse to start a family in. They can sense a good find from miles away, because carrion serves as a food source for countless members of nature's clean-up crew. But because these beetles want to live in these corpses, they don't want to share their discovery. As a result, burying beetles have clever ways of claiming their decaying prize all for themselves. In new research published in The American Naturalist, researchers from UConn and The University of Bayreuth have found these beetles recruit microbes to help throw rivals off the scent.

Immediately following the death of an organism, decomposition begins. The body's building processes cease, and microbes begin un-building and recycling the corpse. Proteins, composed of amino acid building blocks, are broken down and release egg-y, onion-y, and other well-recognized scents that signal death to some, and opportunity to others. For burying beetles, the scents mean one thing: "home, sweet home."

"Burying beetles are really unusual because of their parental care, which is uncommon in beetles, and carcass preparation is just one expression of their parental care," says lead author and UConn professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Stephen Trumbo.

The problem is, rival carrion feeders sense these same malodorous cues, and the researchers were interested to see how burying beetles contend with this problem.

"Of course, when the beetles find the carcass they are using these odor cues, these same cues are being given off while they begin to use this resource," says Trumbo.

Trumbo explains that the team became interested in this odor controlling behavior and explored the idea that perhaps the beetles were influencing the microbes somehow through the course of processing and preparing the carcass, which he says is one aspect of parental care that has not been considered before.

These experiments began with some puzzling fieldwork. The initial studies were centered about putting various compounds into tubes, poking small holes in the tubes, and placing the tubes next to a dead mouse to see if the compounds in the tubes influenced whether insects found the carcass. Trumbo explains that they started by using compounds known to attract carrion feeding insects and therefore expected those compounds to attract more insects than others,

"We knew a few of the compounds that animals use to find the dead animal, they're mainly sulfur-based compounds and we tested some of them and we weren't getting great results. The 'major compounds' did not have a great effect."

The team decided to let the beetles dig deeper into the question for them by exploring differences between human-prepared and beetle-prepared carcasses (see side bar). Samples of microbially-derived volatile chemicals given off during decomposition were collected and analyzed by colleagues in Germany using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. The differences seen with the beetle-prepared carcasses were surprising,

"We found a couple of compounds that really knocked scent down tremendously and these weren't known to be important before. So in a sense we let the beetles tell us what is important because the beetle is saying 'Ok I need to knock these odors down a lot'."

The researchers found a 20-fold reduction in a compound called methyl thiocyanate, an attractant, when the carcasses were prepared by beetle parents-to-be. They also found that these carcasses emitted an increased amount of dimethyl tri-sulfide (DMTS), a deterrent. In all, the burying beetle-prepared carrion not only emitted less of the attractant, but emitted more of the deterrent leading the researchers to conclude the beetles are actively deceiving their counterpart undertakers.

"We used to think the beetles were sterilizing the mouse with their preparation process, but that is not what they're doing at all, they're completely changing the microbial community and therefore the odors that are released. They are changing and in a sense controlling the more aggressive microbes," says Trumbo.

"The beetles are able to fool the rivals by manipulating the odor profile so they do not recognize the carcass. They put out information to misdirect rival individuals."

Burying beetles are resource specialists, meaning they need to have the right conditions to carry out their life cycle - so without flexibility in conditions, Trumbo says they engage in an active disinformation campaign to mislead rival carrion feeders. By ensuring they have the carcass all to themselves, the parents are better able to provide their young with enough food and safety from other insects who may want to eat their young, and therefore increase the likelihood their brood will make it to adulthood.

"We are finding all these elaborate details about our gut microbes and co-adaptation with gut microbes and specializations. Anytime you have a resource specialist, like the burying beetle, they are going to encounter a similar microbial community every time they find their resource, then they might have some really complex adaptations as well," says Trumbo.

Further work is needed to discern which microbes are recruited or controlled in the preparation process, but the results show that preparation alters the microbial-derived cues to mask the information from other beetles. Trumbo and his colleagues are now looking at cues in different species of burying beetles, and he says they have been approached by another research team hoping to help conserve the endangered species of American burying beetle, where conservationists may be able to use the chemical cues Trumbo's team found for conservation efforts.

"We know microbes are producing volatile chemicals that signal all sorts of things," says Trumbo. "These microbial volatiles are all over the place but we do not know much about how animals manipulate them. This is an interesting case of deception in the animal world."

INFORMATION:

Collaborators include Paula Philbrick of UConn and Sandra Steiger and Johannes Stökl of The University of Bayreuth. The research was supported by The University of Connecticut Research Foundation and by the German Research Foundation.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-21

The NFL playoffs are underway, and fans are finding ways to simulate tailgating during the COVID-19 pandemic. Football watch parties are synonymous with eating fatty foods and drinking alcohol. Have you ever wondered what all of that eating and drinking does to your body?

Researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine simulated a tailgating situation with a small group of overweight but healthy men and examined the impact of the eating and drinking on their livers using blood tests and a liver scan. They discovered remarkably differing responses in the subjects.

"Surprisingly, we found that in overweight men, after an afternoon of eating and drinking, how their bodies reacted to food and drink was not uniform," said Elizabeth Parks, PhD, professor of nutrition and ...

2021-01-21

University of Arizona researchers read between the lines of tree rings to reconstruct exactly what happened in Alaska the year that the Laki Volcano erupted half a world away in Iceland. What they learned can help fine-tune future climate predictions.

In June 1783, Laki spewed more sulfur into the atmosphere than any other Northern Hemisphere eruption in the last 1,000 years. The Inuit in North America tell stories about the year that summer never arrived. Benjamin Franklin, who was in France at the time, noted the "fog" that descended over much of Europe in the aftermath, and correctly reasoned that it led to an unusually cold winter on the continent.

Previous analyses of annual tree rings have shown that the entire 1783 growing season for the spruce ...

2021-01-21

A meteorite that fell in northern Germany in 2019 contains carbonates which are among the oldest in the solar system; it also evidences the earliest presence of liquid water on a minor planet. The high-resolution Ion Probe - a research instrument at the Institute of Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University - provided the measurements. The investigation by the Cosmochemistry Research Group led by Prof. Dr Mario Trieloff was part of a consortium study coordinated by the University of Münster with participating scientists from Europe, Australia and the USA.

Carbonates are ubiquitous rocks on Earth. They can be found in the mountain ranges of the Dolomites, the chalk cliffs on the island of Rügen, and in the coral reefs of the ...

2021-01-21

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive method of brain stimulation, in which electrodes are applied over certain places on the scalp, creating a weak electric field. It is currently used for a variety of purposes: from treating depression and pain syndromes to better acquisition of new words and even sports techniques.

During stimulation, the active electrode can transmit a positive or negative electrical charge. In the former case, this stimulation is called 'anodal'; in the latter one, it is called 'cathodal'. Researchers believe that anodal tDCS generally leads to depolarisation of neurons, which increases the likelihood of their excitation when new information arrives. Cathodal ...

2021-01-21

As the United States struggles to control record-breaking increases in COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations, the roll-out of two approved vaccines offers tremendous hope for saving lives and curbing the pandemic. To achieve success, however, experts estimate that at least 70 to 90 percent of the population must be inoculated to achieve herd immunity, but how can we ensure folks will voluntarily receive a vaccine?

Both vaccines require two injections. Pfizer-BioNTech's second dose must be given 21 days after the first and Moderna's second dose must be administered 28 days after the first. While public health and infectious disease experts have discussed strategies to enhance adherence, including the potential use of financial incentives, ...

2021-01-21

One more piece of the puzzle has fallen into place behind a new drug whose anti-cancer potential was developed at the University of Alberta and is set to begin human trials this year, thanks to newly published research.

"The results provide more justification and rationale for starting the clinical trial in May," said first author John Mackey, professor and director of oncology clinical trials in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry. "It's another exciting stepping stone to finding out if this is going to be a new cancer treatment."

The drug PCLX-001 is designed to selectively kill cancer cells by targeting enzymes ...

2021-01-21

Better grades thanks to your fellow students? A study conducted by the University of Zurich's Faculty of Business, Economics and Informatics has revealed that not only the grade point average, gender and nationality peers can influence your own academic achievement, but so can their personalities. Intensive contact and interaction with persistent fellow students improve your own performance, and this effect even endures in subsequent semesters.

Personality traits influence many significant outcomes in life, such as one's educational attainment, income, career achievements or health. Assistant Professor Ulf Zölitz of the University of Zurich's Department of Economics and Jacobs Center for Productive Youth Development has investigated how one's own personality affects fellow students.

The ...

2021-01-21

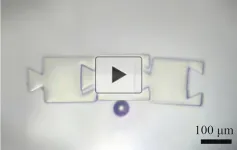

Robots are widely used to build cars, paint airplanes and sew clothing in factories, but the assembly of microscopic components, such as those for biomedical applications, has not yet been automated. Lasers could be the solution. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have used lasers to create miniature robots from bubbles that lift, drop and manipulate small pieces into interconnected structures. Watch a video of the bubble microrobots in action here.

As manufacturing has miniaturized, objects are now being constructed that are only a few hundred micrometers long, or about the thickness of a sheet of paper. But it is hard to position ...

2021-01-21

HOUSTON - (Jan. 20, 2021) - Once upon a time, seasons in Gale Crater probably felt something like those in Iceland. But nobody was there to bundle up more than 3 billion years ago.

The ancient Martian crater is the focus of a study by Rice University scientists comparing data from the Curiosity rover to places on Earth where similar geologic formations have experienced weathering in different climates.

Iceland's basaltic terrain and cool weather, with temperatures typically less than 38 degrees Fahrenheit, turned out to be the closest analog to ancient Mars. The study determined that temperature had the biggest impact on how rocks formed from sediment ...

2021-01-21

Since SARS-CoV-2 was identified in December 2019, researchers have worked feverishly to study the novel coronavirus. Although much knowledge has been gained, scientists still have a lot to learn about how SARS-CoV-2 interacts with the human body, and how the immune system fights it. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science have developed a mathematical model of SARS-CoV-2 infection that reveals a key role for the innate immune system in controlling viral load.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created tremendous socioeconomic problems and caused the death of almost 2 million people worldwide. Although vaccines ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Beetles reveal how to hide the body