Scientists make pivotal discovery on mechanism of Epstein-Barr virus latent infection

Previously unknown enzymatic function of EBNA1 viral protein may instruct new approaches for EBV-associated cancer

2021-01-21

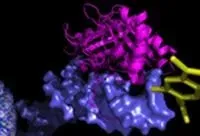

(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA -- (Jan. 21, 2021) -- Researchers at The Wistar Institute have discovered a new enzymatic function of the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) protein EBNA1, a critical factor in EBV's ability to transform human cells and cause cancer. Published in Cell, this study provides new indications for inhibiting EBNA1 function, opening up fresh avenues for development of therapies to treat EBV-associated cancers.

EBV establishes life-long, latent infection in B lymphocytes, which can contribute to development of different cancer types, including Burkitt's lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and Hodgkin's lymphoma.

The Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA1) serves as an attractive therapeutic target for these cancers because it is expressed in all EBV-associated tumors, performs essential activities for tumorigenesis and there are no similar proteins in the human body.

"We discovered an enzymatic activity of EBNA1 that was never described before, despite the intense research efforts to characterize this protein," said Paul M. Lieberman, Ph.D., Hilary Koprowski, M.D., Endowed Professor, leader of the Gene Expression & Regulation Program at Wistar, and corresponding author of the study. "We found that EBNA1 has the cryptic ability to cross-link and nick a single strand of DNA at the terminal stage of DNA replication. This may have important implications for other viral and cellular DNA binding proteins that have similar cryptic enzyme-like activities."

Lieberman and colleagues also found that one specific EBNA1 amino acid called Y518 is essential for this process to occur and, consequently, for viral DNA persistence in the infected cells.

They created a mutant EBNA1 protein in which the critical amino acid was substituted with another and showed that this mutant could not form covalent binding with DNA and perform the endonuclease activity responsible for generating single strand cuts.

In latently infected cells, the EBV genome is maintained as a circular DNA molecule, or episome, that is replicated by cellular enzymes along with the cell's chromosomes. When the cell divides, the two episomal genomes segregate into the two daughter cells.

While it was known that EBNA1 mediates replication and partitioning of the episome during division of the host cell, the exact mechanism was not clear. The new study sheds light on the process and describes how the newly discovered enzymatic activity of EBNA1 is required to complete replication of the viral genome and maintenance of the episomal form.

"Our findings suggest that one could create small molecules to 'trap' the protein bound to DNA and potentially block replication termination and episome maintenance, similar to known inhibitors of topoisomerases," said Jayaraju Dheekollu, Ph.D., first author on the study and staff scientist in the Lieberman Lab. "Such inhibitors may be used to inhibit EBV-induced transformation and treat EBV-associated malignancies."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors: Andreas Wiedmer, Kasirajan Ayyanathan, Julianna S. Deakyne, and Troy E. Messick from The Wistar Institute. K.A. is currently employed at University of Pennsylvania and J.S.D. is currently employed at GlaxoSmithKline.

Work supported by: National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants RO1 CA093606, RO1 423 DE017336, P30 CA010815, and T32 CA09171. Core support for The Wistar Institute was provided by the Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA010815.

Publication information: Cell Cycle-Dependent EBNA1-DNA Cross-Linking Promotes Replication Termination at oriP and Viral Episome Maintenance, Cell (2021). Online publication.

The Wistar Institute is an international leader in biomedical research with special expertise in cancer, immunology, infectious disease research, and vaccine development. Founded in 1892 as the first independent nonprofit biomedical research institute in the United States, Wistar has held the prestigious Cancer Center designation from the National Cancer Institute since 1972. The Institute works actively to ensure that research advances move from the laboratory to the clinic as quickly as possible. wistar.org.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-21

Two out of five individuals delayed or missed medical care in the early phase of the pandemic--from March through mid-July 2020--according to a new survey from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The survey of 1,337 U.S. adults found that 544, or 41 percent, delayed or missed medical care during the survey period. Among the 1,055 individuals who reported needing medical care, 29 percent (307 respondents), indicated fear of transmission of COVID-19 as the main reason. Seven percent (75 respondents) reported financial concerns as the main reason for delaying ...

2021-01-21

Researchers from the University Hospitals in Zurich and Basel, ETH Zurich, University of Zurich and the pharmaceutical company Roche have set out to improve cancer diagnostics by developing a platform of state-of-the-art molecular biology methods. The "Tumor Profiler" project aims to derive the comprehensive molecular profile of tumours in cancer patients, which has the potential to predict the efficacy of a host of new cancer medications. It will therefore make it possible to offer treating physicians personalised and improved therapy recommendations.

Three years ago, the researchers began a large-scale clinical study involving ...

2021-01-21

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- When sheets of two-dimensional nanomaterials like graphene are stacked on top of each other, tiny gaps form between the sheets that have a wide variety of potential uses. In research published in the journal Nature Communications, a team of Brown University researchers has found a way to orient those gaps, called nanochannels, in a way that makes them more useful for filtering water and other liquids of nanoscale contaminants.

"In the last decade, a whole field has sprung up to study these spaces that form between 2-D nanomaterials," said Robert Hurt, a professor in Brown's School of Engineering and coauthor of the ...

2021-01-21

TROY, N.Y. -- Warnings about misinformation are now regularly posted on Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms, but not all of these cautions are created equal. New research from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute shows that artificial intelligence can help form accurate news assessments -- but only when a news story is first emerging.

These findings were recently published in Computers in Human Behavior Reports by an interdisciplinary team of Rensselaer researchers. They found that AI-driven interventions are generally ineffective when used to flag issues with stories on frequently covered ...

2021-01-21

Among the materials known as perovskites, one of the most exciting is a material that can convert sunlight to electricity as efficiently as today's commercial silicon solar cells and has the potential for being much cheaper and easier to manufacture.

There's just one problem: Of the four possible atomic configurations, or phases, this material can take, three are efficient but unstable at room temperature and in ordinary environments, and they quickly revert to the fourth phase, which is completely useless for solar applications.

Now scientists at Stanford ...

2021-01-21

Delivering a minor electric shock into a stream to reveal any fish lurking nearby may be the gold standard for detecting fish populations, but it's not much fun for the trout.

Scientists at Oregon State University have found that sampling stream water for evidence of the presence of various species using environmental DNA, known as eDNA, can be more accurate than electrofishing, without disrupting the fish.

"It's revolutionizing the way we do fish ecology work," said Brooke Penaluna, a research fish biologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service who also has an appointment in OSU's Department ...

2021-01-21

If you believe you are capable of becoming the healthy, engaged person you want to be in old age, you are much more likely to experience that outcome, a recent Oregon State University study shows.

"How we think about who we're going to be in old age is very predictive of exactly how we will be," said Shelbie Turner, a doctoral student in OSU's College of Public Health and Human Sciences and co-author on the study.

Previous studies on aging have found that how people thought about themselves at age 50 predicted a wide range of future health outcomes up to 40 years later -- cardiovascular events, memory, balance, will to live, hospitalizations; even mortality.

"Previous ...

2021-01-21

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - A 72-year-old woman was hospitalized with severe COVID-19 disease, 33 days after the onset of symptoms. She was suffering a prolonged deteriorating illness, with severe pneumonia and a high risk of death, and she was unable to mount her own immune defense against the SARS-CoV-2 virus because of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which compromises normal immunoglobulin production.

But when physicians at the University of Alabama at Birmingham recommended a single intravenous infusion of convalescent blood plasma from her son-in-law -- who had recovered from COVID-19 disease ...

2021-01-21

Microscopy is the workhorse of contemporary life science research, enabling morphological and chemical inspection of living tissue with ever-increasing spatial and temporal resolution. Even though modern microscopes are genuine marvels of engineering, minute deviations from ideal imaging conditions will still lead to optical aberrations that rapidly degrade imaging quality. A mismatch between the refractive indices of the sample and its immersion medium, deviations in the thickness of sample holders or cover glasses, the effects of aging on the instrument--such deviations ...

2021-01-21

Contemporary robots can move quickly. "The motors are fast, and they're powerful," says Sabrina Neuman.

Yet in complex situations, like interactions with people, robots often don't move quickly. "The hang up is what's going on in the robot's head," she adds.

Perceiving stimuli and calculating a response takes a "boatload of computation," which limits reaction time, says Neuman, who recently graduated with a PhD from the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). Neuman has found a way to fight this mismatch between a robot's "mind" and body. The method, called robomorphic computing, uses a robot's physical layout and intended applications ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists make pivotal discovery on mechanism of Epstein-Barr virus latent infection

Previously unknown enzymatic function of EBNA1 viral protein may instruct new approaches for EBV-associated cancer