(Press-News.org) HAMILTON, ON, Jan. 21, 2020 -- McMaster University researchers have established in lab settings that a novel combination of two forms of immunotherapy can be highly effective for treating lung cancer, which causes more deaths than any other form of cancer.

The new treatment, yet to be tested on patients, uses one form of therapy to kill a significant number of lung tumor cells, while triggering changes to the tumor that enable the second therapy to finish the job.

The first therapy employs suppressed "natural killer" immune cells by extracting them from patients' tumours or blood and supercharging them for three weeks. The researchers condition the cells by expanding and activating them using tumour-like feeder cells to improve their effectiveness before sending them back into battle against notoriously challenging lung tumors.

The supercharged cells are very effective on their own, but in combination with another form of treatment called checkpoint blockade therapy, create a potentially revolutionary treatment.

"We've found that re-arming lung cancer patients' natural killer immune cells acts as a triple threat against lung cancer," explains Sophie Poznanski, the McMaster PhD student and CIHR Vanier Scholar who is lead author of a paper published today in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer.

"First, these highly activated cells are able to kill tumour cells efficiently. Second, in doing so, they also reactivate tumour killing by exhausted immune cells within the patients' tumours. And third, they release factors that sensitize patients' tumours to another immunotherapy called immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

"As a result, we've found that the combination of these two therapies induces robust tumour destruction against patient tumours that are initially non-responsive to therapy."

Previous breakthroughs in checkpoint blockade therapy had earned Japanese researcher Tasuku Honjo and American immunologist James Allison the 2018 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology.

Checkpoint blockade therapy works by unlocking cancer's defence against the body's natural immune response. The therapy can be highly effective in resolving even advanced cases of lung cancer - but it only works in about 10 per cent of patients who receive it.

The research team, featuring 10 authors in total, has shown that the supercharged immune cells, when deployed, release an agent that breaks down tumors' resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy, allowing it to work on the vast majority of lung-cancer patients whose tumors would otherwise resist the treatment.

Once activated, the natural killer cells are able to secrete inflammatory factors that help enhance the target of the blockchain that the other immunotherapy treats.

"We needed to find a one-two punch to dismantle the hostile lung tumor environment," says Ali Ashkar, a professor of Medicine and a Canada Research Chair who is Poznanski's research supervisor and the corresponding author on the paper. "Not only is this providing a new treatment for hard-to-treat lung cancer tumors with the natural killer cells, but that treatment also converts the patients who are not responsive to PD1-blockade therapy into highly responsive candidates for this effective treatment".

Such progress is possible because of the close collaboration among clinical practitioners and lab-based researchers at McMaster and its partner institutions, Ashkar says.

He said the team's clinical practitioners, who work with cancer patients every day, provided critical wisdom and collected vital samples from patients at St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton. Ashkar says those clinicians' insights and the samples were integral to the research.

Co-author Yaron Shargall, a professor in and Chief of the Division of Thoracic Surgery at McMaster's Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine and a thoracic surgeon at St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton, says the promising outcome is the result of close links between basic science and clinical medicine.

"It was successful mostly due to the facts that the two groups have spent long hours together, discussing potential ways of combining forces and defining a linkage between a highly specific basic science technology and a very practical clinical, day-to-day dilemmas," he said. "This led to a flawless collaboration which resulted in a very elegant, potentially practice-changing, study."

The researchers are now working to organize a human clinical trial of the combined therapies, a process that could be under way within months, since both immunotherapies have already been approved for individual use.

INFORMATION:

A new study exploring the impact of repeated sleep loss during a simulated working week has found that consuming caffeinated coffee during the day helps to minimize reductions in attention and cognitive function, compared to decaffeinated coffee1.

While this effect occurred in the first three-to-four days of restricted sleep, by the fifth and final day, no difference was seen between caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee drinkers. This therefore suggests that the beneficial effects of coffee for people with restricted sleep are temporary1.

It is estimated that over 30% of adult Western populations sleep less than the recommended seven to eight hours on weekday nights and 15% regularly sleep less than six hours2,3. This can ...

A modelling study suggests that demand for cancer surgery will rise by 52% - equal to 4.7 million procedures - between 2018 and 2040, with the greatest relative increase in low-income countries, which already have substantially lower staffing levels than high-income countries.

A separate observational study comparing global cancer surgery outcomes also suggests that patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are four times more likely to die from colorectal or gastric cancer (odds of 4.59 and 3.72, respectively) than those in high-income countries (HICs) currently, and that poor provision of care ...

Since the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, it has quickly become apparent that children are extremely unlikely to suffer severe COVID-19 illness. Nevertheless, children have had to adjust to the new world of medical staff dressed in personal protective equipment (PPE) in the same way as all other patients. A new study from one of the UK's leading children's hospitals -Alder Hey Children's Hospital in Liverpool - shows that children are not scared by PPE, and can in fact feel reassured by it.

The study was conducted by Drs Charlotte Berwick, Jacinth Tan, Ijeoma Okonkwo and their ...

The sight of healthcare workers wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect against transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is something the world has become accustomed to. However, a new study analysing the impact of PPE staff shows that the number and variety of issues they experience increases as their time in PPE without a break increases, ranging from tiredness and headaches in the first hour to nausea, vomiting and dizziness as they head towards four hours continuously in PPE.

The study is by Dr Tom Hutley, Dr Lynsey Woodward and Mr Joshua Berrington based at the University Hospitals Dorset NHS Foundation Trust, Bournemouth, UK, and was presented at the Winter Scientific ...

The results of a randomised clinical trial with the longest follow up to date show that metabolic surgery is more effective than medications and lifestyle interventions in the long-term control of severe type 2 diabetes.

The study, published today in The Lancet, also shows that over one-third of surgically-treated patients remained diabetes-free throughout the 10-year period of the trial. This demonstrates, in the context of the most rigorous type of clinical investigation, that a "cure" for type 2 diabetes can be achieved.

Researchers from King's College London and the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy report the 10-year outcomes of a trial that compared metabolic surgery with conventional medical and lifestyle interventions in patients ...

Food insecurity spiked among residents living in two predominantly African American neighborhoods during the first weeks of the coronavirus pandemic, far outpacing food insecurity observed among the general U.S. population during the same period, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

Following residents of two Pittsburgh low-income African American neighborhoods characterized as food deserts since 2011, the study found that the pandemic increased the number of people facing food insecurity by nearly 80%.

Similar to United States national trends, food insecurity among residents had been improving consistently since 2011. ...

When drought caused devastating crop losses in Malawi in 2015-2016, farmers in the southeastern African nation did not initially fear for the worst: the government had purchased insurance for such a calamity. But millions of farmers remained unpaid for months because the insurer's model failed to detect the extent of the losses, and a subsequent model audit moved slowly. Quicker payments would have greatly reduced the shockwaves that rippled across the landlocked country.

While the insurers fixed the issues resulting in that error, the incident remains a cautionary tale about the potential failures of agricultural ...

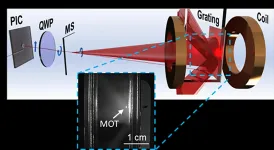

It's cool to be small. Scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have miniaturized the optical components required to cool atoms down to a few thousandths of a degree above absolute zero, the first step in employing them on microchips to drive a new generation of super-accurate atomic clocks, enable navigation without GPS, and simulate quantum systems.

Cooling atoms is equivalent to slowing them down, which makes them a lot easier to study. At room temperature, atoms whiz through the air at nearly the speed of sound, some 343 meters per second. The rapid, randomly moving atoms have only fleeting interactions ...

Black women have higher recurrence and mortality rates than non-Hispanic white women for certain types of breast cancer, according to a University of Illinois Chicago researcher's study published recently in JAMA Oncology.

Dr. Kent Hoskins, associate professor in the UIC College of Medicine's division of hematology/oncology, and co-leader of the Breast Cancer Research group in the University of Illinois Cancer Center, published the study, "Association of race/ethnicity and the 21-gene Recurrence Score with breast cancer-specific mortality among US women" in the Jan. 21 online issue.

Hoskins and the research team sought to discover if breast cancer-specific mortality among women with estrogen ...

Simon Fraser University researchers have found evidence that large ambush-predatory worms--some as long as two metres--roamed the ocean floor near Taiwan over 20 million years ago. The finding, published today in the journal Scientific Reports, is the result of reconstructing an unusual trace fossil that they identified as a burrow of these ancient worms.

According to the study's lead author, SFU Earth Sciences PhD student, Yu-Yen Pan, the trace fossil was found in a rocky area near coastal Taiwan. Trace fossils are part of a research field known as ichnology. "I was fascinated by this monster burrow at first glance," she says. "Compared to other trace fossils which are usually only a few tens of centimetres ...