Supercomputer simulations have helped solve the mystery of how actin filaments polymerize, or chain together. This fundamental research could be applied to treatments to stop cancer spread, develop self-healing materials, and more.

"The major findings of our paper explain a property of actin filaments that has been known for about 50 years or so," said Vilmos Zsolnay, co-author of a study published in November 2020 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

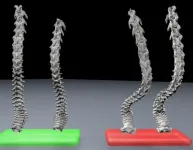

Researchers have known for decades that one end of the actin filament is very different from the other end, and that this polarization is needed for the actin filament to function like it needs to. The mystery has been how the filaments used this polarization to grow, shrink, and bind.

"One end of the actin filament elongates much, much faster than the other at a physiological actin protein concentration," Zsolnay said. "What our study shows is that there is a structural basis for the different polymerization kinetics." Vilmos Zsolnay is a graduate student in the Department of Biophysical Sciences at the University of Chicago, developing simulations in the group of Gregory Voth.

"Actin filaments are what give the cell its shape and many other properties," said Voth, the corresponding author of the study and the Haig P. Papazian Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago. Over time, a cell's shape changes in a dynamic process.

"When a cell wants to move forward, for instance, it will polymerize actin in a particular direction. Those actin filaments then push on the cell membrane, which allow the cell to move in a particular direction." Voth said. What's more, other proteins in the cell help align the actin ends that polymerize, or build up more quickly to push in the exact same direction, directing the cell's path.

"We find that one end of the filament has a very loose connection between actin subunits," Zsolnay said. "That's the fast end. The loose connection within the actin polymer allows incoming actin monomers to have access to a binding site, such that it can make a new connection quickly and the polymerization reaction can continue." He contrasted this to the slow end with very tight connections between actin subunits that block an incoming monomer's ability to polymerize onto that end.

Zsolnay developed the study's all-atom molecular dynamics simulation with the Voth Group on the Midway2 computing cluster at the University of Chicago Research Computing Center. He used GROMACS and NAMD software to investigate the equilibrium conformations of the subunits at the filament ends. "This was one of my first projects using a high performance computing cluster," he said.

XSEDE, the NSF-funded Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, then awarded the scientists allocations on the Stampede2 supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center. "It was very straightforward to test the code on our local cluster here, and then drop a couple of files onto the machines at Stampede2 to start running again within a day," Zsolnay said.

"The high performance computing clusters of Stampede2 are really what allowed this work to take place," he added. "They were able to reach the time and length scales in our simulations that we were interested in. Without the resources provided by XSEDE, we would not have been able to analyze as large of a dataset or have had as much confidence in our findings."

They ran nine simulations, each of roughly a million atoms propagated for about a microsecond. "There are three nucleotide states that we were interested in - the ATP, the ADP plus the gamma phosphate, and once phosphate is released, it's in an ADP nucleotide state." Zsolnay said.

The simulations showed the smoking gun of the mystery - distinct equilibrium conformations between the barbed end and the pointed end subunits, which led to meaningful differences in the contacts between neighboring actin monomer subunits.

An actin monomer in solution has a conformation that's a little wider than when it's part of a longer actin polymer. The previous model, said Zsolnay, assumed that the wide shape transitions into the flattened shape once it polymerizes, almost discretely.

"What we saw when we started the filament with all of the subunits in the flattened state, the ones at the end relaxed to resemble the monomeric state characterized by a wider shape," Zsolnay explained. "At both of the ends, that same mechanism of the widening of the actin molecule led to very different contacts between subunits." At the fast, barbed end there was a separation between the two molecules. Whereas at the pointed end, there was a very tight connection between them.

Research into actin filaments could find wide-ranging applications, such as improving therapeutics. "What's in the news right now is coronavirus," Voth said, referring to the role of the innate immune system. It involves white blood cells called neutrophils that gobble up bacteria or other pathogens in one's blood stream. "What's critical to their ability to sniff out and seek pathogens is their ability to move through an environment and find the pathogens wherever they are. In the immune response, it's very important," he added

And then there's metastatic cancer, where one or a couple of tumor cells will start to migrate, spreading to other parts of the body. "If you could disrupt that in some way, or make it so that it's not as reliable for your cancerous cells, then you could make a cancer treatment based off of that information," Voth said.

"One angle that Prof. Voth and I find particularly interesting is from a materials science standpoint," said Zsolnay. The amino acids in the actin molecule are roughly the same throughout plants, animals, and yeasts. "That gives a hint to us that there's something special about the material properties of actin molecules that can't be reproduced using a different set of amino acids," he added.

This understanding could help advance development of biomimetic materials that repair themselves. "You can imagine, in the future, a new type of material that heals itself. For instance, if a bucket gets a hole in it, the material could sense that a wound has occurred and heal itself, just like human tissue would," Zsolnay added.

Said Voth: "People are really very keen on biomimetic materials - things that behave like these polymers. Our work is explaining a critical thing, which is the polarization of actin filaments."

INFORMATION:

The study, "Structural basis for polarized elongation of actin filaments," was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, November of 2020. The study authors are Vilmos Zsolnay, Harshwardhan H. Katkar, and Gregory A. Voth of the University of Chicago; Steven Z. Chou, Thomas D. Pollard of Yale University. Study funding came from the Department of Defense Army Research Office through Multidisciplinary Research Initiative Grant W911NF1410403; and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under Award R01GM026338.