(Press-News.org) Much of the earth's carbon is trapped in soil, and scientists have assumed that potential climate-warming compounds would safely stay there for centuries. But new research from Princeton University shows that carbon molecules can potentially escape the soil much faster than previously thought. The findings suggest a key role for some types of soil bacteria, which can produce enzymes that break down large carbon-based molecules and allow carbon dioxide to escape into the air.

More carbon is stored in soil than in all the planet's plants and atmosphere combined, and soil absorbs about 20% of human-generated carbon emissions. Yet, factors that affect carbon storage and release from soil have been challenging to study, placing limits on the relevance of soil carbon models for predicting climate change. The new results help explain growing evidence that large carbon molecules can be released from soil more quickly than is assumed in common models.

"We provided a new insight, which is the surprising role of biology and its linkage to whether carbon remains stored" in soil, said coauthor Howard Stone, the Donald R. Dixon '69 and Elizabeth W. Dixon Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

In a paper published Jan. 27 in Nature Communications, the researchers, led by former postdoctoral fellow Judy Q. Yang, developed "soil on a chip" experiments to mimic the interactions between soils, carbon compounds and soil bacteria. They used a synthetic, transparent clay as a stand-in for clay components of soil, which play the largest role in absorbing carbon-containing molecules.

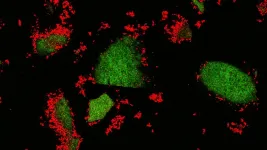

The "chip" was a modified microscope slide, or a microfluidic device, containing silicone-walled channels half a centimeter long and several times the width of a human hair (about 400 micrometers). Inlet and outlet tubes at each end of the channels allowed the researchers to inject the synthetic clay solution, followed by suspensions containing carbon molecules, bacteria or enzymes.

After coating the channels with the see-through clay, the researchers added fluorescently labeled sugar molecules to simulate carbon-containing nutrients that leak from plants' roots, particularly during rainfall. The experiments enabled the researchers to directly observe carbon compounds' locations within the clay and their movements in response to fluid flow in real time.

Both small and large sugar-based molecules stuck to the synthetic clay as they flowed through the device. Consistent with current models, small molecules were easily dislodged, while larger ones remained trapped in the clay.

When the researchers added Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common soil bacterium, to the soil-on-a-chip device, the bacteria could not reach the nutrients lodged within the clay's small pores. However, the enzyme dextranase, which represents enzymes released by certain soil bacteria, could break down the nutrients within the synthetic clay and make smaller sugar molecules available to fuel bacterial metabolism. In the environment, this could lead large amounts of CO2 to be released from soil into the atmosphere.

Researchers have often assumed that larger carbon compounds are protected from release once they stick to clay surfaces, resulting in long-term carbon storage. Some recent field studies have shown that these compounds can detach from clay, but the reason for this has been mysterious, said lead author Yang, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton and is now an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota.

"This is a very important phenomenon, because it's suggesting that the carbon sequestered in the soil can be released [and play a role in] future climate change," said Yang. "We are providing direct evidence of how this carbon can be released -- we found out that the enzymes produced by bacteria play an important role, but this has often been ignored by climate modeling studies" that assume clay protects carbon in soils for thousands of years.

The study sprang from conversations between Stone and coauthor Ian Bourg, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and the High Meadows Environmental Institute. Stone's lab has used microfluidic devices to study the properties of synthetic fibers and bacterial biofilms, while Bourg has expertise in the surface geochemistry of clay minerals -- which are thought to contribute most to soil carbon storage due to their fine-scale structure and surface charges.

Stone, Bourg and their colleagues realized there was a need to experimentally test some of the assumptions in widely used models of carbon storage. Yang joined Stone's group to lead the research, and also collaborated with Xinning Zhang, an assistant professor of geosciences and the High Meadows Environmental Institute who investigates the metabolisms of bacteria and their interactions with the soil environment.

Jinyun Tang, a research scientist in the climate sciences department at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, noted that in recent years he and others have observed the degradation of large carbon molecules in soils and hypothesized that it was mediated by biologically produced enzymes.

The Princeton team's observations "provide a very strong support to our hypothesis," said Tang, who was not involved in the study. He added that the study's technique could also be used to explore such questions as "Will the reversible interaction between small-size carbon molecules and clay particles induce carbon starvation to the microbes and contribute to carbon stabilization? And how do such interactions help maintain microbial diversity in soil? It is a very exciting start."

Future studies will test whether bacteria in the model system can release their own enzymes to degrade large carbon molecules and use them for energy, releasing CO2 in the process.

While the carbon stabilization Tang described is possible, the newly discovered phenomenon could also have the opposite effect, contributing to a positive feedback loop with the potential to exacerbate the pace of climate change, the study's authors said. Other experiments have shown a "priming" effect, in which increases in small sugar molecules in soil lead to release of soil carbon, which may in turn cause bacteria to grow more quickly and release more enzymes to further break down larger carbon molecules, leading to still further increases in bacterial activity.

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the Grand Challenges program and the Carbon Mitigation Initiative of Princeton's High Meadows Environmental Institute.

DALLAS, Jan. 27, 2021 -- Heart disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, according to the American Heart Association's Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics -- 2021 Update, published today in the Association's flagship journal Circulation, and experts warn that the broad influence of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely continue to extend that ranking for years to come.

Globally, nearly 18.6 million people died of cardiovascular disease in 2019, the latest year for which worldwide statistics are calculated. That reflects a 17.1% increase over the past decade. There were more than 523.2 million cases of cardiovascular disease in 2019, an increase ...

(Boston)--When severely or chronically injured, the liver loses its ability to regenerate.

A new study led by researchers at the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) and Boston Medical Center (BMC) now describes a safe new potential therapeutic tool for the recovery of liver function in chronic and acute liver diseases.

Researchers utilized the lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated messenger RNA (mRNA-LNP) currently used in COVID-19 vaccines, to deliver regenerative factors to injured livers in a timely, controlled fashion. "We found that this intervention successfully induces the rapid expansion of the functional ...

New York - The results of the Peoples' Climate Vote, the world's biggest ever survey of public opinion on climate change are published today. Covering 50 countries with over half of the world's population, the survey includes over half a million people under the age of 18, a key constituency on climate change that is typically unable to vote yet in regular elections.

Detailed results broken down by age, gender, and education level will be shared with governments around the world by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ...

DALLAS (SMU) - Wildfires are the enemy when they threaten homes in California and elsewhere. But a new study led by SMU suggests that people living in fire-prone places can learn to manage fire as an ally to prevent dangerous blazes, just like people who lived nearly 1,000 years ago.

"We shouldn't be asking how to avoid fire and smoke," said SMU anthropologist and lead author Christopher Roos. "We should ask ourselves what kind of fire and smoke do we want to coexist with."

An interdisciplinary team of scientists published a study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences documenting centuries of fire management ...

The United States Department of Agriculture identifies a group of "big eight" foods that causes 90% of food allergies. Among these foods are wheat and peanuts.

Sachin Rustgi, a member of the Crop Science Society of America, studies how we can use breeding to develop less allergenic varieties of these foods. Rustgi recently presented his research at the virtual 2020 ASA-CSSA-SSSA Annual Meeting.

Allergic reactions caused by wheat and peanuts can be prevented by avoiding these foods, of course. "While that sounds simple, it is difficult in practice," says Rustgi.

Avoiding wheat and peanuts means losing out ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Tomatoes are one of the most popular types of fresh produce consumed worldwide, as well as being an important ingredient in many manufactured foods.

As with other cultivated crops, some potentially useful genes that were present in its South American ancestors were lost during domestication and breeding of the modern tomato, Solanum lycopersicum var. lycopersicum.

Because of its importance as a crop, the tomato genome sequence was completed and published as long ago as 2012, with later additions and improvements. Now, the team at University of Tsukuba, in collaboration with TOKITA Seed Co. Ltd, have produced high-quality genome sequences of two wild ancestors of tomato from Peru, Solanum pimpinellifolium ...

Children of all ages can completely bypass age verification measures to sign-up to the world's most popular social media apps including Snapchat, Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, WhatsApp, Messenger, Skype and Discord by simply lying about their age, researchers at Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software have discovered.

And even potential age verification solutions identified by the research team can be easily sidestepped by children, according to the team's most recent study: Digital Age of Consent and Age Verification: Can They Protect Children?

Lead researcher Lero's Dr Liliana Pasquale, assistant professor at University College ...

Harpy eagles are considered by many to be among the planet's most spectacular birds. They are also among its most elusive, generally avoiding areas disturbed by human activity - therefore already having vanished from portions of its range - and listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as being 'Near-Threatened'.

However, new research led by the University of Plymouth (UK) suggests estimates of the species' current distribution are potentially overestimating range size.

Using a combination of physical sightings and environmental data, they developed a spatial modelling framework which aims to estimate current and past distributions based on the birds' preferred habitat conditions.

The authors then used the model to estimate a ...

Multi-disciplinary researchers at The University of Manchester have helped develop a powerful physics-based tool to map the pace of language development and human innovation over thousands of years - even stretching into pre-history before records were kept.

Tobias Galla, a professor in theoretical physics, and Dr Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, a specialist in historical linguistics, from The University of Manchester, have come together as part of an international team to share their diverse expertise to develop the new model, revealed in a paper entitled 'Geospatial distributions reflect temperatures of linguistic feature' authored by Henri Kauhanen, Deepthi Gopal, ...

(Scottsdale, Ariz. - January 27, 2021) HIRREM (the legacy research technology of Cereset - a Brain State Company) was utilized by the Wake Forest School of Medicine to study symptoms of traumatic stress in military personnel before and after use of Cereset (legacy) intervention.

Whole brain, resting state magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done pre- and post- Cereset intervention. Significant effects on brain network connectivity have been previously reported.

For the current study, lateralization of brain connectivity was analyzed. Lateralization here refers to the distribution of brain connections within the right, and left side, or to the opposite side. This is important because common lobes in the ...