(Press-News.org) COLLEGE PARK, Md.--The amount of methane released into the atmosphere as a result of coal mining is likely much higher than previously calculated, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union recently.

The study estimates that methane emissions from coal mines are approximately 50 percent higher than previously estimated. The research was done by a team at the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and others.

The higher estimate is due mainly to two factors: methane that continues to be emitted from thousands of abandoned mines and the higher methane content in coal seams that are ever deeper, according to chief author Nazar Kholod of PNNL.

The results have important implications for Earth's climate because methane is about 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide when it comes to warming the planet over a long period. In addition to coal mining, other major sources of methane emissions globally include wetlands, agriculture, and oil and gas facilities.

The study is one of the first to account for methane leaking from old, abandoned mines. Kholod said that when a closed mine is flooded, water stops methane from leaking almost completely within about seven years. But when an abandoned mine is closed without flooding, as many are, methane leaks into the air for decades.

Methane emissions are a constant concern at coal mines, which vent the gas as it's emitted when coal seams are disturbed. While methane produced in some industries is captured and used to create additional energy, it's more difficult to capture from coal mines, where the gas typically makes up a tiny fraction of the overall air stream.

Globally, coal mining is decreasing in the United States and Europe but increasing rapidly in other parts of the world, such as southeast Asia and India. The authors point out that less coal production doesn't translate to less methane.

"As more coal mines close, the share of coal mines that have been abandoned but are still emitting methane will increase," said Kholod. He is a scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute, a partnership between PNNL and the University of Maryland where researchers explore the interactions between human, energy and environmental systems.

More methane from deeper and defunct mines

The research team analyzed 250 coal samples from around the world, including North America, South America, Australia, Asia and Europe. The team found that coal from depths greater than 400 meters--depths many new mines reach--contains more than twice as much methane as coal mined at depths less than 200 meters. Mines are getting deeper every year.

The study is the first to attempt to account for methane escaping from abandoned mines. The reason is straightforward, Kholod said: Good data sets are hard to come by. His paper drew largely on data from the United States and Ukraine, countries where data about coal mine status and methane is fully available. In the United States in 2015, about one-third of abandoned mines were flooded. Ukraine reported that all its mines abandoned that year were flooded.

The team estimated that in 2010, 103 billion cubic meters of methane were released from working underground and surface mines and an additional 22 billion cubic meters from abandoned mines. That total of 125 billion cubic meters for 2010 is 50 percent higher than the estimate of 83 billion cubic meters for that year by the Community Emissions Data System, a highly regarded system developed by PNNL researchers and collaborators used for analyzing historical emissions data.

While the results are based on actual measurements from coal mines around the world, the scientists suggest further studies that take into account more such measurements from coal mines, including abandoned mines, would be helpful.

The future: More methane emissions from mines very likely

The study analyzed future methane emissions from coal mines under a range of scenarios. If efforts to address climate change remain similar to what they have been, the researchers estimate that methane emissions as a result of coal mining will increase dramatically by the end of the century: Nearly eight times what they are today from abandoned mines and four times what they are from working mines.

But Nazar notes that there is uncertainty about future coal production. If coal production decreases, then emissions from working mines would decrease.

However, in all scenarios, methane emissions from abandoned mines are expected to grow more quickly than those from established mines. The team cites deeper mines, more abandoned mines, and a greater percentage of surface mines from which methane escapes more freely as reasons why.

Those increases are significantly higher than what current climate models call for--for instance, 83 percent higher in 2050 than suggested by the widely used Global Change Analysis Model developed by PNNL.

The study estimates that if strong climate mitigation strategies are put in place, then by the end of this century the amount of methane escaping from abandoned mines would be about the same as 2020. Under the same conditions, the amount of methane escaping from working mines would be cut in half.

"If you stop producing coal, that doesn't mean that methane will stop being emitted from coal mines," said Kholod. "We can't just take coal out of the equation."

INFORMATION:

JGCRI scientist Meredydd Evans is also an author of the paper. Other authors include Raymond Pilcher of Raven Ridge Resources of Grand Junction, Colo.; Volha Roshchanka and Felicia Ruiz of the EPA; and Michael Coté and Ron Collings of Ruby Canyon Engineering of Grand Junction, Colo.

The research was funded by the EPA and the Global Methane Initiative.

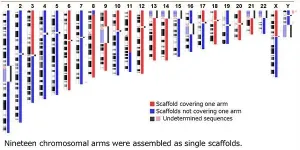

The Japanese now have their own reference genome thanks to researchers at Tohoku University who completed and released the first Japanese reference genome (JG1).

Their study was published in the journal Nature Communications on January 11, 2021.

"JG1 can aid with the clinical sequence analysis of Japanese individuals with rare diseases as it eliminates the genomic differences from the international reference genome," said Jun Takayama, co-author of the study.

Back in 2003, the Human Genome Project, through a gargantuan global effort, cracked the code of life and mapped all the genes of the human genome.

Since then, more accurate versions of the human reference genome have ...

The researchers of the Institute for Atmospheric and Earth system research at the University of Helsinki have investigated how atmospheric particles are formed in the Arctic. Until recent studies, the molecular processes of particle formation in the high Arctic remained a mystery.

During their expeditions to the Arctic, the scientists collected measurements for 12 months in total. The results of the extensive research project were recently published in the Geophysical Research Letters journal.

The researchers discovered that atmospheric vapors, particles, and cloud formation have clear differences within various Arctic environments. The study clarifies how Arctic warming and sea ice loss strengthens processes where different vapors are emitted to the atmosphere. The ...

The Covid-19 pandemic has made home offices, virtual meetings and remote learning the norm, and it is likely here to stay. But are people paying attention in online meetings? Are students paying attention in virtual classrooms? Researchers Jens Madsen and Lucas C. Parra from City College of New York, demonstrate how eye tracking can be used to measure the level of attention online using standard web cameras, without the need to transfer any data from peoples computers, thus preserving privacy. In a paper entitled "Synchronized eye movements predict test scores in online video education," published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they show that just ...

Scientists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and ETH Zurich have developed a process to produce commodity chemicals in a much less hazardous way than was previously possible. Such commodity chemicals represent the starting point for many mass-produced products in the chemical industry, such as plastics, dyes, and fertilizers, and are usually synthesized with the help of chlorine gas or bromine, both of which are extremely toxic and highly corrosive. In the current issue of Science, the researchers report that they have been able to utilize electrolysis, i.e., the application of an electric current, to obtain chemicals known as dichloro and dibromo compounds, which can then be used to synthesize ...

A new study has found that mobile apps can play a vital role in helping immigrants integrate into new cultures, as well as provide physical and mental health benefits.

Researchers at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) surveyed new migrants and refugees undertaking free beginners' language classes in Greece, often the first destination for people arriving into Europe from Africa and Asia, over a 10-month period.

The findings, published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior, show that those using mobile apps aided by artificial intelligence (AI), such as language assistants, customised information sites, or health symptom trackers, experienced ...

New research has revealed how an invasion of the alien evergreen tree, Prosopis juliflora seriously diminishes water resources in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, consuming enough of this already scarce resource to irrigate cotton and sugarcane generating some US$ 320 million and US$ 470 million net benefits per year.

A team of Ethiopian, South African and Swiss scientists, including lead author Dr Hailu Shiferaw, Dr Tena Alamirew, and Dr Gete Zeleke from the Water and Land Resource Centre of Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, and Dr Sebinasi Dzikiti from Stellenbosch University, ...

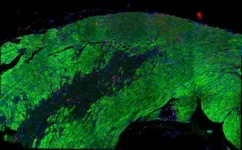

Scientists have broadened our understanding of how 'weak' cells bond with their more mature cellular counterparts to boost the body's production of insulin, improving our knowledge of the processes leading to type 2 diabetes - a significant global health problem.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus occurs when β-cells cannot release enough insulin - a tightly controlled process requiring hundreds of such cells clustered together to co-ordinate their response to signals from food, such as sugar, fat and gut hormones.

An international research team - led by scientists at the University of ...

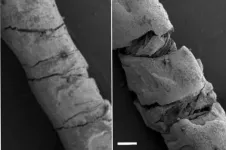

Engineers at Tufts University have created and demonstrated flexible thread-based sensors that can measure movement of the neck, providing data on the direction, angle of rotation and degree of displacement of the head. The discovery raises the potential for thin, inconspicuous tatoo-like patches that could, according to the Tufts team, measure athletic performance, monitor worker or driver fatigue, assist with physical therapy, enhance virtual reality games and systems, and improve computer generated imagery in cinematography. The technology, described today in Scientific Reports, adds to a growing number of thread-based ...

Researchers from the Hubrecht Institute mapped the recovery of the heart after a heart attack with great detail. They found that heart muscle cells - also called cardiomyocytes - play an important role in the intracellular communication after a heart attack. The researchers documented their findings in a database that is accessible for scientists around the world. This brings the research field a step closer to the development of therapies for improved recovery after heart injury. The results were published in Communications Biology on the 29th of January.

In the Netherlands, an average of 95 people end up in the hospital each day ...

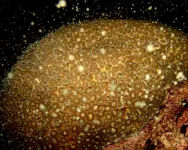

Efforts to understand when corals reproduce have been given a boost thanks to a new resource that gives scientists open access to more than forty years' worth of information about coral spawning.

Led by researchers at Newcastle University, UK, and James Cook University, Australia, the Coral Spawning Database (CSD) for the first time collates vital information about the timing and geographical variation of coral spawning. This was a huge international effort that includes over 90 authors from 60 institutions in 20 countries.

The data can be used by scientists and conservationists to better understand the environmental cues that influence when coral ...