(Press-News.org) Remember the first rule of fight club? That's right: You don't talk about fight club. Luckily, the rules of Hollywood don't apply to science. In new published research, University of Arizona researchers report what they learned when they started their own "fight club" - an exclusive version where only insects qualify as members, with a mission to shed light on the evolution of weapons in the animal kingdom.

In many animal species, fighting is a common occurrence. Individuals may fight over food, shelter or territory, but especially common are fights between males over access to females for mating. Many of the most striking and unusual features of animals are associated with these mating-related fights, including the horns of beetles and the antlers of deer. What is less clear is which individuals win these fights, and why they have the particular weapon shapes that they do.

"Biologists have generally assumed that the individual who inflicts more damage on their opponent will be more likely to win a given fight," said John J. Wiens, a professor in the University of Arizona Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, who co-authored two recent studies on bug battles. "Surprisingly, this fundamental assumption had yet to be tested in an experimental study."

To find out who wins fights and why, Zachary Emberts, a postdoctoral fellow in Wiens's lab and lead author of both studies, collected 300 male insects known as leaf-footed bugs from the desert near Tucson, Arizona, and staged one-on-one fights.

In the summer, these bugs can be found occupying mesquite trees in great numbers, where they crowd the branches and jostle each other over access to females. The males fight using enlarged spikes on their hind legs.

So, what does a fight between leaf-footed bugs look like? The best analogy, according to Emberts, is a college wrestling match.

Configure

"They come up on each other, and they lock each other in, and they will try to squeeze themselves toward one another with their weaponized legs, and that is how they inflict the damage," he said.

"Think of it as a wrestling match where the opponents sneak knives in," Wiens added.

Emberts and Wiens were specifically interested in investigating whether damage influences who wins these fights. For this experiment, published in the journal Functional Ecology, they chose a particular species of leaf-footed bugs: giant mesquite bugs, a common species of the desert Southwest.

In addition to the spikes on their legs, the males also have increased thickness in the part of their wings where the spikes usually strike, suggesting that this thickening acts as natural armor during fights. The researchers attached pieces of faux leather to the wings of 50 of their test insects, to provide extra armor against punctures from the spikes of rivals.

The researchers found that individuals with this extra armor were 1.6 times more likely to win fights than individuals without extra armor or with the same amount of armor placed in a different location.

"This tells us that damage is important in who wins the fights," Emberts said. "This had previously been hypothesized, and it makes intuitive sense, but it had not been experimentally shown before."

The other major question the researchers wanted to investigate: Why do weapons differ among species? Different species of leaf-footed bugs have different arrangements of spikes on their legs. For example, some sport a lone, big spike, while others have a row of several small ones.

"Evolution has produced an incredible diversity of weapons in animals, but we don't fully understand why," Emberts said. "And if selection favors weapons that inflict the most damage, then why don't all weapons look the same?"

Emberts and Wiens said they chose to look at leaf-footed bugs because the damage from their spikes can easily be measured, as the weapons leave distinct holes in their opponents' wings. The holes don't close up, so once a bug suffers this kind of damage, it has to live with it for the rest of its life.

"We can directly count and measure the holes they make in their opponents' wings," Wiens said, "and we find that certain weapon morphologies cause more and bigger holes."

In their second study, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Emberts and Wiens tested the idea that the evolution of different weapon shapes is related to how much damage these weapons can cause.

They measured the shape and size of hindlimb spikes in 17 species of leaf-footed bugs from around the world. They also measured the average amount of damage on the forewing of each species, including the size and number of punctures from the spikes. The work was done in collaboration with Wei Song Hwang, curator of entomology at the National University of Singapore.

The results revealed that some weapons are more effective than others at causing damage to opponents.

"This tells us that much of the weapon diversity seen in animals that fight over resources and mates can be explained by how well different weapons perform at inflicting damage," Wiens said. "How well the weaponry is performing - how much damage it inflicts in fights - is driving its diversification."

In other words, certain blade designs provide an evolutionary edge (pun intended). But these results came with a surprise, too.

"Very different looking weapons can also inflict the same average amount of damage," Emberts said. "This tells us there could be multiple solutions to inflicting damage."

For example, two distantly related species of leaf-footed bugs were found to cause almost identical amounts of damage: In one species, the males carry several spines on their femur, while the other species bears a single spine on the tibia.

"This finding helps answer the question, why don't all weapons evolve to look the same?" Wiens explained. "Rather than evolving towards one optimal weapon shape, there are very different shapes that perform almost as well, solving the mystery of why weapons look so different among species."

The authors suggest that the basic principles that explain weapon diversity in leaf-footed bugs might also apply to other groups of animals in which different species have different weapon shapes, such as horned mammals.

Emberts and Wiens have begun experiments to tease apart the physiological reasons underlying the evolutionary cost of suffering damage from fights. They say we should stay tuned for more news from UArizona's very own "Bug Fight Club."

INFORMATION:

Publications:

"Defensive structures influence fighting outcomes," Functional Ecology, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13730

"Weapon performance drives weapon evolution," Proceedings of the Royal Society B, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.2898

PHILADELPHA--Inflammation in the blood could serve as a new biomarker to help identify patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who won't respond to the immune-stimulating drugs known as CD40 agonists, suggests a new study from researchers in the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania published in JCI Insight

It is known that pancreatic cancer can cause systemic inflammation, which is readily detectable in the blood. The team found that patients with systemic inflammation had worse overall survival rates than patients without inflammation when treated with both a CD40 agonist and the chemotherapy gemcitabine.

The ...

This study is the first randomised control trial to rigorously test a sequential approach to treating comorbid PTSD and major depressive disorder.

Findings from a trial of 52 patients undergoing three types of treatment regime - using only Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), using Behavioural Activation Therapy (BA) with some CPT, or CPT with some BA - found that a combined treatment protocol resulted in meaningful reductions in PTSD and depression severity, with improvements maintained at six-month follow-up investigations.

"We sought to examine whether a protocol that specifically targeted both PTSD and comorbid ...

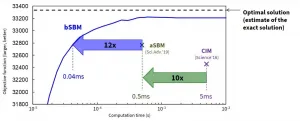

TOKYO --Toshiba Corporation (TOKYO: 6502) and Toshiba Digital Solutions Corporation (collectively Toshiba), industry leaders in solutions for large-scale optimization problems, today announced the Ballistic Simulated Bifurcation Algorithm (bSB) and the Discrete Simulated Bifurcation Algorithm (dSB), new algorithms that far surpass the performance of Toshiba's previous Simulated Bifurcation Algorithm (SB). The new algorithms will be applied to finding solutions to highly complex problems in areas as diverse as portfolio management, drug development and logistics management. ...

Borderline Personality Disorder, or BPD, is the most common personality disorder in Australia, affecting up to 5% of the population at some stage, and Flinders University researchers warn more needs to be done to meet this high consumer needs.

A new study in the Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing (Wiley) describes how people with BPD are becoming more knowledgeable about the disorder and available treatments, but may find it difficult to find evidence-based help for their symptoms.

The South Australian psychiatric researchers warn these services are constrained by stigma ...

Researchers at Flinders University are working to remedy this situation by identifying what triggers this chronic pain in the female reproductive tract.

Dr Joel Castro Kraftchenko - Head of Endometriosis Research for the Visceral Pain Group (VIPER), with the College of Medicine and Public Health at Flinders University - is leading research into the pain attached to Dyspareunia, also known as vaginal hyperalgesia or painful intercourse, which is one of the most debilitating symptoms experienced by women with endometriosis and vulvodynia.

Pain is detected by specialised proteins (called ion channels) that are present in sensory nerves and project from peripheral organs to the central ...

Researchers from the international BASE collaboration at CERN, Switzerland, which is led by the RIKEN Fundamental Symmetries Laboratory, have discovered a new avenue to search for axions--a hypothetical particle that is one of the candidates of dark matter particles. The group, which usually performs ultra-high precision measurements of the fundamental properties of trapped antimatter, has for the first time used the ultra-sensitive superconducting single antiproton detection system of their advanced Penning trap experiment as a sensitive dark matter antenna.

If our current understanding of cosmology is correct, ordinary "visible" matter only ...

When health researchers ask pregnant women about their alcohol use, expectant women may underreport their drinking, hampering efforts to minimize alcohol use in pregnancy and prevent development of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) in children.

In a recently published study in Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, University of New Mexico scientists found that pregnant women's reporting of their own risky drinking varies greatly depending on how key questions are worded.

Most women know that alcohol use during pregnancy may harm their unborn child - and that leads to fear of being ...

Genetics contributes to the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, and the APOE gene is the strongest genetic risk factor, specifically the APOE4 allele. However, it has been known for a while that the risk due to the APOE4 allele differs considerably across populations, with Europeans having a greater risk from the APOE4 allele than Africans and African Americans.

"If you inherited your APOE4 allele from your African ancestor, you have a lower risk for Alzheimer disease than if you inherited your APOE4 allele from your European ancestor," said Jeffery M. Vance, M.D., Ph.D., professor and founding chair of ...

ATLANTA - FEBRUARY 4, 2021 - Cancer ranks as a leading cause of death in every country in the world, and, for the first time, female breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer, overtaking lung cancer, according to a collaborative report, Global Cancer Statistics 2020, from the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Data show that 1 in 5 men and women worldwide develop cancer during their lifetime, and 1 in 8 men and 1 in 11 women die from the disease.

The article describes cancer incidence and mortality at the global level and according to sex, geography, ...

Niigata, Japan - Researchers from the Graduate School of Science and Technology at Niigata University, Japan along with their collaborators from Tokyo University of Science (Japan), Yamagata University (Japan) and University of Regensburg (Germany) have published a scientific article which enhances clarity on the understanding of proton conduction mechanism in protic ionic liquids. The findings which were recently published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry B sheds light on the transport of hydrogen ions in these liquids, which opens new avenues for the development of novel energy generation and storage devices.

With ...