(Press-News.org) Wintertime outbreaks of COVID-19 have been largely driven by whether people adhere to control measures such as mask wearing and social distancing, according to a study published Feb. 8 in Nature Communications by Princeton University researchers. Climate and population immunity are playing smaller roles during the current pandemic phase of the virus, the researchers found.

The researchers -- working in summer 2020 -- ran simulations of a wintertime coronavirus outbreak in New York City to identify key factors that would allow the virus to proliferate. They found that relaxing control measures in the summer months led to an outbreak in the winter regardless of climate factors.

"Our results implied that lax control measures -- and likely fatigue with complying with control measures -- would fuel wintertime outbreaks," said first author Rachel Baker, an associate research scholar in Princeton's High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI). Baker and her co-authors are all affiliated with the HMEI Climate Change and Infectious Disease initiative.

"Although we have witnessed a substantial number of COVID-19 cases, population-level immunity remains low in many locations," Baker said. "This means that if you roll back enforcement or adherence to control measures, you can still expect a large outbreak. Climate factors including winter weather play a secondary role and certainly don't help."

The researchers found that even maintaining rigid control measures through the summer can lead to a wintertime outbreak if climate factors provided enough of a boost to viral transmission. "If summertime controls are holding the transmissibility of coronavirus at a level that only just mitigates an outbreak, then winter climate conditions can push you over the edge," Baker said. "Nonetheless, having effective control measures in place last summer could have limited the winter outbreaks we're now experiencing."

Cases have climbed in many northern hemisphere locations since November. In the United States, spikes in COVID-19 cases are thought to be tied to increased travel and gatherings for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Notably, outbreaks were recorded in temperate locations such as Los Angeles in addition to regions with much colder conditions, Baker said. At the same time, large outbreaks were observed in South Africa from November to January, which are that country's summer months.

"The greater incidence of COVID-19 in various environs really speaks to the climate's limited role at this stage," Baker said.

In May, the same authors published a paper in the journal Science suggesting that local climate variations would be unlikely to affect the coronavirus pandemic. The paper suggested that hopes that the warmer conditions of summer would slow the transmission of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, in the northern hemisphere were unrealistic.

Gabriel Vecchi, a professor of geosciences and the High Meadows Environmental Institute and co-author of both studies, said that the virus currently spreads too quickly and that people are too susceptible for climate to be a determining factor.

"The influence of climate and weather on infection rates should become more evident -- and thus a potentially useful source of information for disease prediction -- as growing immunity moves the disease into endemic phases from the present epidemic stage," Vecchi said.

The most recent study provides insight on how scientists can determine the impact of various factors on the virus at various times, said co-author C. Jessica Metcalf, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs and an HMEI associated faculty member.

"An important challenge that we tackle here is balancing the role of many potential factors on the trajectory of the epidemic," Metcalf said. "As the pandemic progresses, both natural and vaccinal immunity will play an increasing role, underscoring the importance of developing a handle on the landscape of immunity."

Critical factors to consider when projecting the future of COVID-19 are emerging variants of the virus, as well as how efforts to contain coronavirus have changed other diseases, said co-author Bryan Grenfell, the Kathryn Briger and Sarah Fenton Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Public Affairs and associated faculty in HMEI.

In November, Grenfell and his co-authors in the Climate Change and Infectious Disease initiative published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as mask wearing and social distancing could result in large, delayed outbreaks of endemic diseases such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

"The interaction between NPIs and immunity will become even more complex as a variety of vaccines are deployed and new viral variants arise," Grenfell said. "Understanding the impact of these variables underlines the importance of immune surveillance and greatly expanded viral sequencing."

Additional authors of the current paper include Wenchang Yang, an associate research scholar in geosciences at Princeton.

INFORMATION:

The paper, "Assessing the influence of climate on wintertime SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks" was published online Feb. 8 by Nature Communications. This work was supported by the Cooperative Institute for Modelling the Earth System (CIMES), the High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI) and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS).

Ancient Amazonian communities fortified valuable land they had spent years making fertile to protect it from conflict, excavations show.

Farmers in Bolivia constructed wooden defences around previously nutrient-poor tropical soils they had enriched over generations to keep them safe during times of social unrest.

These long-term soil management strategies allowed Amazonians to grow nutrient demanding crops, such as maize and manioc and fruiting trees, and this was key to community subsistence. These Amazonian Dark Earths, or Terra Preta, were created through burning, mulching, and the deposition of organic waste.

It was known that some communities built ditches ...

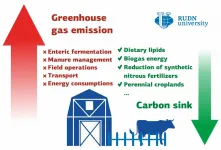

An ecologist from RUDN University suggested a method to evaluate and reduce the effect of animal farms on climate change and developed a set of measures for small farms that provides for the complete elimination of greenhouse gas emissions. The results of the study were published in the Journal of Cleaner Production.

Crop and animal farming and other agricultural activities account for almost a quarter of all greenhouse gases produced by humanity and therefore add a lot to climate change. On the other hand, the soils and biomass accumulate a lot of carbon, thus preventing it from getting into the atmosphere as a part of carbon dioxide and slowing climate change down. An ecologist from RUDN University suggested ...

Ithaca, NY--Love them or hate them, there's no doubt the European Starling is a wildly successful bird. A new study from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology examines this non-native species from the inside out. What exactly happened at the genetic level as the starling population exploded from just 80 birds released in New York City's Central Park in 1890, peaking at an estimated 200 million breeding adults spread all across North America? The study appears in the journal Molecular Ecology.

"The amazing thing about the evolutionary changes among starling populations ...

The term "algae" is used to refer to over 72,500 identified aquatic species. The size of algae is up to tens of meters, however, most (about 80%) of the species are much smaller - they comprise the microalgae group. Microalgae are rich in nutrients and biologically active substances such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins, pigments and others. These components are widely used in food, cosmetic, chemical and energy industries. Biotechnology of microalgae has multiple advantages: they are a renewable and sustainable resource, more productive than terrestrial plants due to their high growth rate and lack of seasonality ...

LAWRENCE -- Traditional burial in a graveyard has environmental costs. Graves can take up valuable land, leak embalming chemicals and involve nonbiodegradable materials like concrete, as well as the plastic and steel that make up many caskets. But the other mainstream option -- cremation -- releases dangerous chemicals and greenhouse gasses into the environment.

So, what's an environmentalist to do when making plans for the end of life?

A new study from the University of Kansas in the journal Mortality details how older environmentalists consider death care and how likely they are to choose "green" burials and other eco-friendly options.

"This article is specifically asking if older adult environmentalists consider how their bodies are going to ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- A ruler and scale can tell archaeologists the size and weight of a fragment of pottery - but identifying its precise color can depend on individual perception. So, when a handheld color-matching gadget came on the market, scientists hoped it offered a consistent way of determining color, free of human bias.

But a new study by archaeologists at the Florida Museum of Natural History found that the tool, known as the X-Rite Capsure, often misread colors readily distinguished by the human eye.

When tested against a book of color chips, the machine failed to produce correct color scores in 37.5% of cases, even though its software system included the same set of chips. In an analysis of fired ...

Individually, California blackworms live an unremarkable life eating microorganisms in ponds and serving as tropical fish food for aquarium enthusiasts. But together, tens, hundreds, or thousands of the centimeter-long creatures can collaborate to form a "worm blob," a shape-shifting living liquid that collectively protects its members from drying out and helps them escape threats such as excessive heat.

While other organisms form collective flocks, schools, or swarms for such purposes as mating, predation, and protection, the Lumbriculus variegatus worms are unusual in their ability to braid themselves together to accomplish tasks that unconnected individuals cannot. A new study reported by researchers at ...

HOUSTON - (Feb. 9, 2021) - Finding a needle in a haystack is hard enough. But try finding a specific molecule on the needle.

Rice University researchers have achieved something of the sort with a new genome editing tool that targets the supporting players in a cell's nucleus that package DNA and aid gene expression. Their work opens the door to new therapies for cancer and other diseases.

Rice bioengineer Isaac Hilton, postdoctoral researcher and lead author Jing Li and their colleagues programmed a modified CRISPR/Cas9 complex to target specific histones, ubiquitous epigenetic proteins that keep DNA in order, ...

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- A team led by astronomers at the University of California, Riverside, has found that some dwarf galaxies may today appear to be dark-matter free even though they formed as galaxies dominated by dark matter in the past.

Galaxies that appear to have little to no dark matter -- nonluminous material thought to constitute 85% of matter in the universe -- complicate astronomers' understanding of the universe's dark matter content. Such galaxies, which have recently been found in observations, challenge a cosmological model used by astronomers called Lambda Cold Dark Matter, or LCDM, where all galaxies are surrounded by a massive and extended dark matter halo.

Dark-matter-free galaxies are not well understood in the astronomical community. ...

UCLA RESEARCH ALERT

FINDINGS

In a study of mice, researchers at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified a new approach that combines an anti-psychotic drug, a statin used to lower high cholesterol levels, and radiation to improve the overall survival in mice with glioblastoma. Glioblastoma is one of the deadliest and most difficult-to-treat brain tumors. Researchers found the triple combination extended the median survival 4-fold compared to radiation alone.

BACKGROUND

Radiation therapy is part of the standard-of-care treatment regimen for glioblastoma, often helping prolong the survival of patients. However, survival times have not improved significantly over the past two decades and attempts to improve the efficacy ...