(Press-News.org) Palo Alto, CA-- Understanding how plants respond to stressful environmental conditions is crucial to developing effective strategies for protecting important agricultural crops from a changing climate. New research led by Carnegie's Zhiyong Wang, Shouling, Xu, and Yang Bi reveals an important process by which plants switch between amplified and dampened stress responses. Their work is published by Nature Communications.

To survive in a changing environment, plants must choose between different response strategies, which are based on both external environmental factors and internal nutritional and energy demands. For example, a plant might either delay or accelerate its lifecycle, depending on the availability of the stored sugars that make up its energy supply.

"We know plants are able to modulate their response to environmental stresses based on whether or not nutrients are available," Wang explained. "But the molecular mechanisms by which they accomplish this fine tuning are poorly understood."

For years, Carnegie plant biologists have been building a treasure trove of research on a system by which plants sense available nutrients. It is a sugar molecule that gets tacked onto proteins and alters their activities. Called O-linked N-Acetylglucosamine, or O-GlcNAc, this sugar tag is associated with changes in gene expression, cellular growth, and cell differentiation in both animals and plants.

The functions of O-GlcNAc are well studied in the context of human diseases, such as obesity, cancer, and neurodegeneration, but are much less understood in plants. In 2017, the Carnegie-led team identified for the first time hundreds of plant proteins modified by O-GlcNAc, providing a framework for fully parsing the nutrient-sensing network it controls.

In this most recent report, researchers from Wang's lab--lead author Bi, Zhiping Deng, Dasha Savage, Thomas Hartwig, and Sunita Patil--and Xu's lab--Ruben Shrestha and Su Hyun Hong--revealed that one of the proteins modified by an O-GlcNAc tag provides a cellular physiological link between sugar availability and stress response. It is an evolutionarily conserved protein named Apoptotic Chromatin Condensation Inducer in the Nucleus, or Acinus, which is known in mammals to play numerous roles in the storage and processing of a cell's genetic material.

Through a comprehensive set of genetic, genomic, and proteomic experiments, the Carnegie team demonstrated that in plants Acinus forms a similar protein complex as its mammalian counterpart and plays a unique role in regulating stress responses and key developmental transitions, such as seed germination and flowering. The work further demonstrates that sugar modification of the Acinus protein allows nutrient availability to modulate a plant's sensitivity to environmental stresses and to control seed germination and flowering time.

"Our research illustrates how plants use the sugar sensing mechanisms to fine tune stress responses," Xu explained. "Our findings suggest that plants choose different stress response strategies based on nutrient availability to maximize their survival in different stress conditions."

Looking forward, the researchers want to study more proteins that are tagged by O-GlcNAc and better understand how this important system could be harnessed to fight hunger.

"Understanding how plants make cellular decisions by integrating environmental and internal information is important for improving plant resilience and productivity in a changing climate," Wang concluded. "Considering that many parts of the molecular circuit are conserved in plant and human cells, our research findings can lead to improvement of not only agriculture and ecosystems, but also of human health."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Carnegie Institution for Science endowment.

The Carnegie Institution for Science (carnegiescience.edu) is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with three research divisions on both coasts. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in the life and environmental sciences, Earth and planetary science, and astronomy and astrophysics.

A negative experience with food usually leaves us unable to stomach the thought of eating that particular dish again. Using sugar-loving snails as models, researchers at the University of Sussex believe these bad experiences could be causing a switch in our brains, which impacts our future eating habits.

Like many other animals, snails like sugar and usually start feeding on it as soon as it is presented to them. But through aversive training which involved tapping the snails gently on the head when sugar appeared, the snails' behaviour was altered and they refused to feed on the sugar, even when hungry.

When the team ...

FRANKFURT. More than two thirds of the earth is covered by clouds. Depending on whether they float high or low, how large their water and ice content is, how thick they are or over which region of the Earth they form, it gets warmer or cooler underneath them. Due to human influence, there are most likely more cooling effects from clouds today than in pre-industrial times, but how clouds contribute to climate change is not yet well understood. Researchers currently believe that low clouds over the Arctic and Antarctic, for example, contribute to the warming of these regions by blocking the direct radiation of long-wave heat from the Earth's surface.

All ...

Low-income middle-aged African-American women with high blood pressure very commonly suffer from depression and should be better screened for this serious mental health condition, according to a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The researchers found that in a sample of over 300 low-income, African-American women, aged 40-75, with uncontrolled hypertension, nearly 60 percent screened positively for a diagnosis of depression based on a standard clinical questionnaire about depressive symptoms.

The results appeared February 10 in JAMA Psychiatry.

"Our findings suggest that low-income, middle-aged African-American women with hypertension really should be screened for depression symptoms," ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- People who participated in a health education program that included both mental health and physical health information significantly reduced their risks of cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases by the end of the 12-month intervention - and sustained most of those improvements six months later, researchers found.

People who participated in the integrated mental and physical health program maintained significant improvements on seven of nine health measures six months after the program's conclusion. These included, on average, a 21% ...

New research shows that biodiversity is important not just at the traditional scale of short-term plot experiments--in which ecologists monitor the health of a single meadow, forest grove, or pond after manipulating its species counts--but when measured over decades and across regional landscapes as well. The findings can help guide conservation planning and enhance efforts to make human communities more sustainable.

Published in a recent issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, the multi-institutional study was led by Dr. Christopher Patrick ...

STEMOs (Stroke-Einsatz-Mobile) have been serving Berlin for ten years. The specialized stroke emergency response vehicles allow physicians to start treating stroke patients before they reach hospital. For the first time, a team of researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin has been able to show that the dispatch of mobile stroke units is linked to improved clinical outcomes. The researchers' findings, which show that patients for whom STEMOs were dispatched were more likely to survive without long-term disability, have been published in JAMA*.

The phrase 'time is brain' emphasizes a fundamental principle from emergency medicine, namely that after stroke, every minute counts. Without ...

With the help of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF's NOIRLab, and other ground-based telescopes, astronomers have confirmed that a faint object discovered in 2018 and nicknamed "Farfarout" is indeed the most distant object yet found in our Solar System. The object has just received its designation from the International Astronomical Union.

Farfarout was first spotted in January 2018 by the Subaru Telescope, located on Maunakea in Hawai'i. Its discoverers could tell it was very far away, but they weren't sure exactly how far. They needed more observations.

"At that time we did not know the object's orbit as we only had the Subaru discovery observations over 24 hours, but it takes years of ...

A report summary released today by a team at Lehigh University led by Thomas McAndrew , a computational scientist and assistant professor in Lehigh's College of Health, shares the consensus results of experts in the modeling of infectious disease when asked to rank the top 5 most effective interventions to mitigate the spread and impact of COVID-19 in the U.S.

The report is part of an ongoing meta forecasting project aimed at translating forecasting and real world experience into actions.

McAndrew and his colleagues wanted to answer "Here is where ...

Wilmington, DE, Feb. 11, 2020 -Scientists have developed an affordable, downloadable app that scans for potential unintended mistakes when CRISPR is used to repair mutations that cause disease. The app reveals potentially risky DNA alterations that could impede efforts to safely use CRISPR to correct mutations in conditions like sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis. The development of the new tool, called DECODR (which stands for Deconvolution of Complex DNA Repair), was reported today in The CRISPR Journal by researchers from ChristianaCare's Gene Editing Institute.

"Our research has shown that when CRISPR is used to repair a gene, it also can introduce a variety of subtle changes to DNA near the site of the repair," said Eric ...

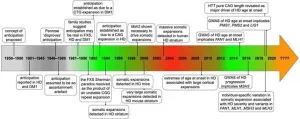

Amsterdam, February 11, 2021 - Recent genetic data from patients with Huntington's disease (HD) show that DNA repair is an important factor that determines how early or late the disease occurs in individuals who carry the expanded CAG repeat in the HTT gene that causes HD. The processes of DNA repair further expand the CAG repeats in HTT in the brain implicated in pathogenesis and disease progression. This special issue of the Journal of Huntington's Disease (JHD) is a compendium of new reviews on topics ranging from the discovery of somatic CAG repeat expansion in HD, to our current understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved ...