Researchers find parallels in spread of brain cancer in mammals, zebrafish

Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC scientists say zebrafish suitable models for human glioblastoma research

2021-02-12

(Press-News.org) Scientists at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC have identified a new zebrafish model that could help advance glioblastoma multiforme research. Glioblastoma is an aggressive form of primary brain tumor - fewer than one in 20 patients survive five years after diagnosis.

The research team previously discovered that human-derived brain cancer cells in mice use the brain's blood vessels like highways to spread away from the original mass. In the new study, published in ACS Pharmacology and Translational Science, they show clear cross-over between mammals and fish and describe similar observations in zebrafish.

"Our hope is that this new work in zebrafish will help researchers efficiently evaluate new, much-needed therapeutics in a pre-clinical animal model to target these aggressive and devastating tumors," said Harald Sontheimer, formerly a professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at the time of the study.

When brain cancer cells disperse, they become harder to locate and delete. Even when the original tumor is surgically removed, migratory glioblastoma cells can linger - undetected by diagnostic imaging - eventually forming new satellite tumors if they can endure chemotherapy or radiation therapies.

As the cancer cells migrate, they also leave a destructive wake.

"Our previous research showed that glioma cells exploit the brain's blood vessels. Tumor cells use blood vessels as a pathway to invade within the brain and consequently break down the blood-brain barrier," said Robyn Umans, postdoctoral associate in Sontheimer's laboratory at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and the study's lead author.

But what if there were a way to block glioma cells from leveraging blood vessels to control cancer cell migration?

Rodent studies led by other researchers revealed that gliomas need a key signaling pathway - Wnt, named for the wingless flies it was first observed in - in order to exploit blood vessels. When Umans added a Wnt inhibitor molecule to the zebrafish's water, they noticed a change in glioma cell behavior -- the cancer cells had reduced attachments to the brain's vasculature.

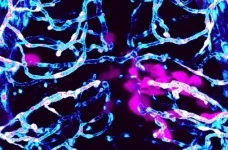

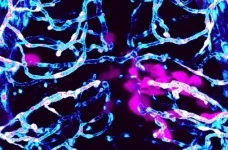

Zebrafish skin and scales are crystal clear. Scientists can put the fish under a microscope and, with fluorescent markers, watch cancer cells grow, migrate, and interact with other cells - all in real-time.

Fast-growing zebrafish are also efficient, less expensive to maintain than other preclinical models, and they share 70 percent of the same DNA as humans.

"For me, seeing is believing. With zebrafish models I can see biological mechanisms underlying aggressive cancers come to life in real-time, gaining this unprecedented visibility into the tumor microenvironment," Umans said. "Our hope is that these proof-of-principal experiments validate the zebrafish model as an additional platform for cancer drug discovery."

The researchers also wanted to see if the glioma cells also metastasized using blood vessels outside of the brain, so they injected a handful of cells into the fish's peripheral tissue. This group of cancer cells attempted to travel to the brain, but they didn't latch onto any pre-existing blood vessels. Instead, nearby vessels appeared to stem offshoots that grew toward the cancer cells like a magnet, suggesting angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels - a hallmark of many cancers that helps assure steady nutrient supply.

"This was a rare and special opportunity to, as a postdoc, establish a new model organism for a lab," Umans said. "This study was an exciting collaboration because two of the authors were undergraduate researchers who contributed significantly to imaging and analysis, as well as a senior principal investigator. It was really rewarding to mentor these amazing, young scientists and see a study go from the creation of a fish room to a publication."

INFORMATION:

Additional authors included former Virginia Tech School of Neuroscience undergraduate students, Mattie ten Kate and Carolyn Pollock, who is now a laboratory technician in the research institute's Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory for COVID-19.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-12

COLUMBUS, Ohio - On the outskirts of some small Indigenous communities in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, a few volunteer guards keep watch along roads blocked by makeshift barricades of chains, stones and wood.

The invader they are trying to stop is COVID-19.

For many of Mexico's Indigenous people, poor and ignored by state and federal governments, the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic is one that rests primarily with themselves, said Jeffrey Cohen, a professor of anthropology at The Ohio State University.

That means they must take steps like limiting access to their villages.

"Most of these communities only have ...

2021-02-12

peer review/experimental study/animals/cells

Researchers from Uppsala University show in a new study that inhibition of the protein EZH2 can reduce the growth of cancer cells in the blood cancer multiple myeloma. The reduction is caused by changes in the cancer cells' metabolism. These changes can be used as markers to discriminate whether a patient would respond to treatment by EZH2 inhibition. The study has been published in the journal Cell Death & Disease.

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer where immune cells grow in an uncontrolled way in the bone marrow. The disease is very difficult to treat and is still considered incurable, and thus it is urgent to identify new therapeutic targets in the cancer cells.

The research group behind ...

2021-02-12

TROY, N.Y. -- An antioxidant found in green tea may increase levels of p53, a natural anti-cancer protein, known as the "guardian of the genome" for its ability to repair DNA damage or destroy cancerous cells. Published today in Nature Communications, a study of the direct interaction between p53 and the green tea compound, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), points to a new target for cancer drug discovery.

"Both p53 and EGCG molecules are extremely interesting. Mutations in p53 are found in over 50% of human cancer, while EGCG is the major anti-oxidant in green tea, a popular beverage worldwide," said END ...

2021-02-12

DURHAM, N.C. -- Humans aren't the only mammals that form long-term bonds with a single, special mate -- some bats, wolves, beavers, foxes and other animals do, too. But new research suggests the brain circuitry that makes love last in some species may not be the same in others.

The study, appearing Feb. 12 in the journal Scientific Reports, compares monogamous and promiscuous species within a closely related group of lemurs, distant primate cousins of humans from the island Madagascar.

Red-bellied lemurs and mongoose lemurs are among the few species in the lemur family tree in which male-female partners stick together year after year, working together to raise their young and defend their territory.

Once bonded, pairs spend much of their waking hours grooming ...

2021-02-12

Every year around 20 Australian children die from the incurable brain tumour, Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG). The average age of diagnosis for DIPG is just seven years. There are no effective treatments, and almost all children die from the disease, usually within one year of diagnosis.

A paper published today 12 Feb 2021 in the prestigious journal, Nature Communications, reveals a potential revolutionary drug combination that - in animal studies and in world first 3D models of the tumour - is "spectacularly effective in eradicating the cancer cells," according to lead researcher and paediatric oncologist Associate Professor David Ziegler, from the Children's Cancer Institute and Sydney Children's Hospital.

In ...

2021-02-12

Children treated for cancer with approaches such as chemotherapy can develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (a second type of cancer) with a dismal prognosis. Scientists at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital have characterized the genomic abnormalities of 84 such myeloid neoplasms, with potential implications for early interventions to stop the disease. A paper detailing the work was published today in Nature Communications.

The somatic (cancer) and germline (inherited) genomic alterations that drive therapy-related myeloid neoplasms in children have not been comprehensively ...

2021-02-12

(Friday, February 12, 2021 - Toronto) -- Inhibiting a key enzyme that controls a large network of proteins important in cell division and growth paves the way for a new class of drugs that could stop glioblastoma, a deadly brain cancer, from growing.

Researchers at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and University of Toronto, showed that chemically inhibiting the enzyme PRMT5 can suppress the growth of glioblastoma cells.

The inhibition of PRMT5 led to cell senescence, similar to what happens to cells during aging when cells lose the ability to divide and grow. Cellular senescence can also be a powerful tumour suppression mechanism, stopping ...

2021-02-12

Space: the final frontier. What's stopping us from exploring it? Well, lots of things, but one of the major issues is space radiation, and the effects it can have on astronaut health during long voyages. A new review in the open-access journal END ...

2021-02-12

Research over the last 20 years has shown that atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the arterial blood vessel wall. Soluble mediators such as cytokines and chemokines are pivotal players in this disease, promoting vascular inflammation. However, the development of anti-inflammatory therapeutics directed against such mediators that could prevent atherosclerosis has proven difficult, despite promising clinical studies in the recent past.

Previous anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies to prevent atherosclerosis, heart attacks, strokes, rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases have mainly been based ...

2021-02-12

Remote sensing technology has become a vital tool for scientists over the past several decades for monitoring changes in land use, ice cover, and vegetation across the globe. Satellite imagery, however, is typically available at only coarse resolutions, allowing only for the analysis of broad trends over large areas. Remote-controlled drones are an increasingly affordable alternative for researchers working at finer scales in ecology and agriculture, but the laser-based technology used to estimate plant productivity and biomass, such as light detection and ranging (LiDAR), remain prohibitively expensive.

In research presented in a recently published issue of Applications in Plant Sciences, researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers find parallels in spread of brain cancer in mammals, zebrafish

Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC scientists say zebrafish suitable models for human glioblastoma research