(Press-News.org) Our brains are complicated webs of billions of neurons, constantly transmitting information across synapses, and this communication underlies our every thought and movement.

But what happens to the circuit when a neuron dies? Can other neurons around it pick up the slack to maintain the same level of function?

Indeed they can, but not all neurons have this capacity, according to new research from the University of Chicago. By studying several neuron pairs that innervate distinct muscles in a fruit fly model, researchers found that some neurons compensate for the loss of a neighboring partner.

The results, published February 17, 2021, in the Journal of Neuroscience, are a step in the direction of understanding the plasticity of the brain and using that knowledge to better understand not only normal development, but also neurodegenerative diseases.

"Now that we know that some neurons can compensate when other neurons die, we can ask whether this process can also happen in neurological diseases," said Robert Carrillo, PhD, assistant professor of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology and corresponding author of the paper.

Because the human brain is incredibly complex, researchers use the comparatively simple fruit fly model to investigate fundamental neuroscience concepts that could potentially translate to our higher-order brains.

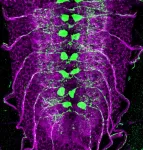

To better understand how the brain adapts to structural and functional changes, Carrillo and graduate student Yupu Wang examined the fruit fly's neuromuscular system, where each muscle is innervated by two motor neurons. While it is known that neurons can alter their activity when perturbations happen at their own synapses, a process known as synaptic plasticity, they wondered what would happen if one neuron was removed from the system. Would the other neurons respond and compensate for this loss?

It's not an easy question to answer: Removing single neurons without simultaneously destroying other neurons is difficult, and it is also difficult to measure a single neuron's baseline activity. The researchers solved this by expressing cell death-promoting genes in a very specific subset of motor neurons. They then used imaging and electrophysiological recordings to isolate the activity of the single remaining neuron in the pair.

In one muscle, they found that the remaining neuron expanded its synaptic arbor and compensated for both the spontaneous and evoked neurotransmission of its missing neighbor. When the researchers performed the same procedure on two other muscles, however, they found that the remaining neuron did not compensate for the loss of its neighbor.

"It appears that some neurons have the ability to detect and compensate for their neighboring neuron, and others do not," said Wang, who is doing his graduate studies in the Committee on Development, Regeneration and Stem Cell Biology.

That could be because, as the researchers found, each neuron has different functional properties. The neuron that compensated for the loss of its neighbor also contributed most to the overall activity of the muscle under baseline conditions.

This still left the researchers with an intriguing question: How does the remaining neuron know how much to compensate? They hypothesized that the neuron pairs work together to establish a "set point" for activity upon circuit formation. Indeed, they found that if the neuron's neighbor never forms synapses - if the system never knew it was supposed to get information from two neurons - then the remaining neuron will not compensate.

That leaves hope that further studies could help illuminate whether neurons whose neighbors are affected by neurogenerative diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which causes progressive neuron death and loss of muscle function, could show synaptic plasticity.

Next the researchers are studying the mechanism that causes the compensation. They hope to better understand how the signal that the neuron has died is sent, and how that signal in turn causes the other neuron to compensate.

INFORMATION:

The study, "Structural and Functional Synaptic Plasticity Induced by Convergent Synapse Loss in the Drosophila Neuromuscular Circuit," was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K01-NS-102342 and T32-GM-007183, the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division, and the Grossman Institute for Neuroscience, Quantitative Biology and Human Behavior. Additional authors include Meike Lobb-Rabe, James Ashley and Veera Anand.

About the University of Chicago Medicine & Biological Sciences

The University of Chicago Medicine, with a history dating back to 1927, is one of the nation's leading academic health systems. It unites the missions of the University of Chicago Medical Center, Pritzker School of Medicine and the Biological Sciences Division. Twelve Nobel Prize winners in physiology or medicine have been affiliated with the University of Chicago Medicine. Its main Hyde Park campus is home to the Center for Care and Discovery, Bernard Mitchell Hospital, Comer Children's Hospital and the Duchossois Center for Advanced Medicine. It also has ambulatory facilities in Orland Park, South Loop and River East as well as affiliations and partnerships that create a regional network of care. UChicago Medicine offers a full range of specialty-care services for adults and children through more than 40 institutes and centers including an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Together with Harvey-based Ingalls Memorial, UChicago Medicine has 1,296 licensed beds, nearly 1,300 attending physicians, over 2,800 nurses and about 970 residents and fellows.

Visit UChicago Medicine's health and science news blog at http://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront.

Twitter @UChicagoMed

Facebook.com/UChicagoMed

Facebook.com/UChicagoMedComer

Scientists have used cutting-edge research in quantum computation and quantum technology to pioneer a radical new approach to determining how our Universe works at its most fundamental level.

An international team of experts, led by the University of Nottingham, have demonstrated that only quantum and not classical gravity could be used to create a certain informatic ingredient that is needed for quantum computation. Their research "Non-Gaussianity as a signature of a quantum theory of gravity" has been published today in PRX Quantum.

Dr Richard Howl led the research during his time at the University of Nottingham's School of Mathematics, he said: "For ...

One early feature of reporting on the coronavirus pandemic was the perception that sub-Saharan Africa was largely being spared the skyrocketing infection and death rates that were disrupting nations around the world.

While still seemingly mild, the true toll of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, on the countries of sub-Saharan Africa may be obscured by a tremendous variability in risk factors combined with surveillance challenges, according to a study published in the journal Nature Medicine by an international team led by Princeton University researchers and supported by Princeton's High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI).

"Although ...

Adequate spacing between births can help to alleviate the likelihood of stunting in children, according to a new study from the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI).

In an article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, TCI postdoctoral associate Sunaina Dhingra and Director Prabhu Pingali find that differences in height between firstborn and later-born children may be due to inadequate time between births. When children are born at least three years after their older siblings, the height gap between them disappears.

India's family planning policies have focused on lowering population growth and postponing pregnancy to improve maternal health outcomes. But while the overall fertility rate has fallen as low ...

WASHINGTON -- Researchers have developed an extremely sensitive miniaturized optical fiber sensor that could one day be used to measure small pressure changes in the body.

"Our new pressure sensor was designed for medical applications and overcomes many of the issues of using silica-based fibers," said research team leader Hwa-Yaw Tam from The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. "It is sensitive enough to measure pressure inside lungs while breathing, which changes by just a few kilopascals."

The researchers describe their new optical fiber sensor in The ...

A new X-ray imaging scanner to help surgeons performing breast tumour removal surgery has been developed by UCL experts.

Most breast cancer operations are what are known as conserving surgeries, which remove the cancerous tumour rather than the whole breast. Second operations are often required if the margins (edges) of the extracted tissue are found to not be clear of cancer.

Researchers at UCL, Queen Mary University of London, Barts Health NHS Trust and Nikon used a new approach to x-ray imaging which allows surgeons to assess extracted tissue intraoperatively, or during the initial surgery, giving 2.5 times better detection of diseased tissue in the margins than with standard ...

Polyisobutenyl succinic anhydrides (PIBSAs) are important for the auto industry because of their wide use in lubricant and fuel formulations. Their synthesis, however, requires high temperatures and, therefore, higher cost.

Adding a Lewis acid--a substance that can accept a pair of electrons--as a catalyst makes the PIBSA formation more efficient. But which Lewis acid? Despite the importance of PIBSAs in the industrial space, an easy way to screen these catalysts and predict their performance hasn't yet been developed.

New research led by the Computer-Aided Nano and Energy Lab (CANELa) at the University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering, in collaboration with the ...

Wearable sleep tracking devices - from Fitbit to Apple Watch to never-heard-of brands stashed away in the electronics clearance bin - have infiltrated the market at a rapid pace in recent years.

And like any consumer products, not all sleep trackers are created equal, according to West Virginia University neuroscientists.

Prompted by a lack of independent, third-party evaluations of these devices, a research team led by Joshua Hagen, director of the Human Performance Innovation Center at the WVU Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, tested the efficacy of eight commercial sleep trackers.

Fitbit and Oura came out on top in measuring total sleep time, total wake ...

SAN ANTONIO -- Patients should be assessed for frailty before having many types of surgery, even if the surgery is considered low risk, a review of two national patient databases shows.

Frailty is a clinical syndrome marked by slow walking speed, weak grip, poor balance, exhaustion and low physical activity. It is an important risk factor for death after surgery, although the association between frailty and mortality across surgical specialties is not well understood.

The study, conducted by faculty at multiple institutions including The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio), mined patient data from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality ...

The millions of people affected by 2020's record-breaking and deadly fires can attest to the fact that wildfire hazards are increasing across western North America.

Both climate change and forest management have been blamed, but the relative influence of these drivers is still heavily debated. The results of a recent study show that in some ecosystems, human-caused climate change is the predominant factor; in other places, the trend can also be attributed to a century of fire suppression that has produced dense, unhealthy forests.

Over the past decade, fire scientists have made major progress in understanding climate-fire relationships at large scales, such as across western North America. But a new paper published in the journal Environmental Research ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a novel proton therapy technique to more specifically target cancer cells that resist other forms of treatment. The technique is called LEAP, an acronym for "biologically enhanced particle therapy." The findings are published today in Cancer Research, the journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"The human body receives tens of thousands of DNA lesions per day from a variety of internal and external sources," says Robert Mutter, M.D., a radiation oncologist at Mayo Clinic and co-principal investigator of the study." Therefore, cells have evolved complex repair pathways to efficiently repair damaged DNA. Defects in these repair pathways ...