(Press-News.org) Evidence that a sense of our physical selves can develop even without the sense of touch has been uncovered in a new study by researchers in the UK and the United States.

The research shows that if someone loses their sense of touch and 'proprioception' - their sense of body position - as an adult, they may learn compensatory skills using visual cues and conscious thought, or reasoning, to move their bodies.

Someone who has never had a sense of touch or proprioception, however, can find faster, unconscious ways of processing visual cues to move and orient themselves.

A team at the University of Birmingham collaborated with researchers at Bournemouth University and the University of Chicago on the study, published in Experimental Brain Research.

The team worked with two individuals - called Ian and Kim - who have had unique sensory experiences: Ian developed a complete loss of tactile sense and proprioception (sense of body position), together called somatosensation, below his neck after an autoimmune response to an illness as a teenager. Kim was born without somatosensation, lacking the sensory nerve fibres needed to feel her body.

The researchers were interested in learning how the human brain adapts to a loss of sensory information and how it might compensate if this information is not present in the first place.

"There are a lot of questions about how we form a sense of the body and of the self," said Peggy Mason, Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Chicago. "Body and self are very integrated, and your sense of your physical self is present when you close your eyes -- but without a sense of touch or proprioception, it really wouldn't be.

"Kim has a unique condition, where she is operating on vision, hearing, and the vestibular system. She doesn't have touch or proprioception and never has. Ian is in a very different situation, because he had these senses and lost them. We were interested in whether or not a person can take visual information that's not involved in visual perception and feed it into some place in the brain that is responsible for generating a sense of your body. Essentially, can you use that to have a sense of the body when you're seeing it?"

For the study, Kim and Ian came into the lab at the University of Birmingham, along with age-matched control subjects, to participate in a number of experiments designed to assess both their mental image of their bodies as well as their unconscious sense of their bodies in space.

These included reporting on the shape and size of their hands by moving a cursor on a screen to locate landmarks like fingertips and knuckles, and estimating their 'reach' distance (the length of their arm).

The study found a number of similarities and, intriguingly, differences in how Kim and Ian performed in the experiments. In the hand experiment, for example, Kim's estimation of her hand shape and size was close to the control group's, being wider and shorter than her actual hand, whereas Ian's was much more accurate.

Lead researcher, Chris Miall, Professor of Motor Neuroscience at the University of Birmingham, says: "We think the differences between Ian's and Kim's responses relate to the visual control that both of them use to navigate their environment. For Ian, this is a very conscious process and he has learned to use visual cues to continually evaluate and monitor that environment. For Kim the process is much more unconscious. She still uses the visual information, but in a more instinctive and intuitive way."

Co-author Jonathan Cole, Professor of Clinical Neurophysiology at Bournemouth University, adds: "You and I have habits and skills that are not conscious, but Ian has to think about movement the whole time."

These results indicate that if someone loses their sense of touch and proprioception as an adult, they may be able to learn compensatory skills, using visual input and conscious thought to move their bodies.

However, a person who never experiences somatosensation may be able to develop mechanisms to bypass the lack of sensation and instead use unconsciously processed visual information to exert motor control.

"What we can learn from this is that you might not do it in the way that others do it, but you will find a way to make a body schema," said Mason. "You will find a way to make a sense of yourself. Kim has found a way. It's not the way that you or I do it, or the way that anyone else on earth might do it, but it's absolutely critical to have that sense of self. You have to be located somewhere. We're not brains in vats!"

INFORMATION:

For more information, please contact Tony Moran, International Communications Manager, University of Birmingham on +44 (0)782 783 2312. For out-of-hours enquiries, please call +44 (0) 7789 921 165.

Notes to editor:

* The University of Birmingham is ranked amongst the world's top 100 institutions. Its work brings people from across the world to Birmingham, including researchers, teachers and more than 6,500 international students from over 150 countries.

* Miall et al (2021). 'Perception of body shape and size without touch or proprioception: evidence from individuals with congenital and acquired neuropathy'. Experimental Brain Research.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, researchers at ETH Zurich discovered the first indications that the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface had been steadily declining since the 1950s. The phenomenon was known as "global dimming". However, a reversal in this trend became discernible in the late 1980s. The atmosphere brightened again at many locations and surface solar radiation increased.

"In previous studies, we showed that the amount of sunlight that reaches the Earth's surface is not constant over many decades but instead varies substantially - a phenomenon known as global dimming and brightening," ...

Researchers from Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, the state's only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, evaluated the frequency of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, on various environmental surfaces in outpatient and inpatient hematology/oncology settings located within Rutgers Cancer Institute and Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, an RWJBarnabas Health facility. The study revealed extremely low detection of SARS-CoV-2 on environmental surfaces across multiple outpatient and inpatient oncology areas, including an active COVID-19 floor. Andrew M. Evens, DO, MSc, FACP, associate director for clinical services and director of the Lymphoma Program at Rutgers Cancer Institute and medical director of the oncology service ...

Annapolis, MD; February 17, 2021--When the invasive spotted lanternfly arrived in the United States in 2014, it was immediately recognized for the threat it posed to native plants and crops. A community of researchers and experts in science, agriculture, and government sprang into action to respond, improving our chances for containing the pest and curbing its potential for damage.

While the effort continues, a new collection curated by the Entomological Society of America's family of journals showcases the growing body of research that is helping us understand the spotted lanternfly's biology and how to contain it. The collection features 25 articles published ...

When there is a choice, wolves in Mongolia prefer to feed on wild animals rather than grazing livestock. This is the discovery by a research team from the University of Göttingen and the Senckenberg Museum Görlitz. Previous studies had shown that the diet of wolves in inland Central Asia consists mainly of grazing livestock, which could lead to increasing conflict between nomadic livestock herders and wild predatory animals like wolves. The study has been published in the journal Mammalian Biology.

Around three million people live in Mongolia, making it the most sparsely populated country in the world. In addition, there are more than 40 million grazing animals. These animals are not just a source of food but also the ...

By 2030 only EV's will be in production, meaning manufacturers are racing to create a high-energy battery that's affordable and charges efficiently, but conventional battery cathodes cannot reach the targets of 500Wh/Kg

Lithium-excess cathodes offer the ability to reach 500Wh/Kg but unlocking their full capacity means understanding how they can store charge at high voltages.

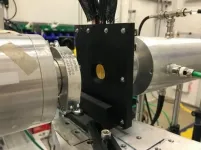

A new X-ray study lead by WMG, University of Warwick has resolved how the metals and oxygen facilitate the charge storage at high voltages.

High energy storage batteries for EVs need high capacity battery cathodes. New lithium-excess magnesium-rich cathodes are expected to replace existing nickel-rich cathodes but understanding how the magnesium and oxygen accommodate charge storage at high ...

As investors set their sights on the mineral resources of the deep seabed, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) is developing regulations that will govern their future exploration and possible exploitation. A new IASS Policy Brief, published in cooperation with the Federal Environment Agency (UBA), presents three recommendations to ensure that future deep seabed mining would be to the common benefit all humankind, as required by international law.

The ecosystems of the deep ocean are complex and provide a wide range of benefits to humankind. Oceans soak up carbon dioxide and act as a natural buffer to global warming in addition to regulating the climate and serving as an important ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Researchers report that 4-6-year-old children who walk further than their peers during a timed test - a method used to estimate cardiorespiratory health - also do better on cognitive tests and other measures of brain function. Published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine, the study suggests that the link between cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive health is evident even earlier in life than previously appreciated.

Most studies of the link between fitness and brain health focus on adults or preadolescent or adolescent children, said doctoral student Shelby Keye, who led the new research with Naiman Khan, a professor of kinesiology and ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Workers with science, technology, engineering and math backgrounds are typically in high demand - but the demand isn't so overwhelming that a "skills gap" exists in the labor market for information technology help desk workers, one of the largest computer occupations in the U.S., says new research from a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign expert who studies labor economics and work issues.

The incidence of prolonged hiring difficulties for STEM workers is modest, with only 11%-15% of IT help desks in the U.S. showing vacancy patterns that might be consistent with persistent hiring frictions, said Andrew Weaver, a professor ...

The mechanism that keeps arterial blood pressure stable in black and white tegu lizards (Salvator merianae) even as their body temperature varies substantially is more efficient at lower than higher external temperatures, contrary to what has always been believed, and vascular regulation plays a key role in pressure adjustments, according to an article published in PLOS ONE by researchers at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The research was supported by FAPESP.

The findings pave the way for more investigation of the physiology of ectothermic animals, which rely on external environmental factors to regulate body temperature, and of novel applications for the method used in ...

A new study concluding out of Lusaka, Zambia last summer has found that as many as 19% (almost 1 in 5) of recently-deceased people tested positive for COVID-19.

A new Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) study in Lusaka, Zambia's capital, challenges the common belief that Africa somehow "dodged" the COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings indicate that low numbers of reported infections and deaths across Africa may simply be from lack of testing, with the coronavirus taking a terrible but invisible toll on the continent.

Published in The BMJ, the study found that at least ...