(Press-News.org) Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – Shooting steady pulses of electricity through slender electrodes into a brain area that controls complex behaviors has proven to be effective against several therapeutically stubborn neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. Now, a new study has found that this technique, called deep brain stimulation (DBS), targets the same class of neuronal cells that are known to respond to physical exercise and drugs such as Prozac.

The study, led by Associate Professor Grigori Enikolopov, Ph.D., of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), is the cover story in the January 1st issue of The Journal of Comparative Neurology, which is currently available online.

The targeted neuronal cells, which increase in number in response to DBS, are a type of precursor cell that ultimately matures into adult neurons in the brain's hippocampus, the control center for spatial and long-term memory, emotion, behavior and other functions that go awry in diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, epilepsy and depression. DBS has been successful in treating some cases of Parkinson's. And recently, it has also proven to work against other brain disorders such as epilepsy and severe depression.

"But the clinical application of DBS to treat neuropsychiatric disorders is still problematic because there isn't a clear rationale or a guide for which brain regions need to be stimulated to achieve maximum therapeutic benefit," says Enikolopov. "Our study now points to the brain region whose stimulation results in new cell growth in the hippocampus, an area that is implicated in many behavioral and cognitive disorders."

Enikolopov has long been interested in understanding how neuronal and neuroendocrine circuits are involved in mood regulation. "To that end, the question we've been asking is whether different types of stimuli, such as exercise or drugs or DBS, target different types of brain cells and circuits or converge on the same targets," he explains.

"There is a well-established correlation between the use of antidepressants and new neuronal growth in the hippocampus," says Enikolopov. "But what we didn't know was which steps in the cascade of events that eventually leads to the birth of new neurons are actually affected." Brain stem cells eventually differentiate into mature neurons following a cascade of steps, each of which produces a different intermediary cell type or precursor.

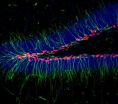

To identify the specific cell type affected by DBS, the CSHL team developed mouse models in which different classes of neural cells such as stem and progenitor cells produce different fluorescent colors. This enabled the scientists to visually track these cell populations and quantitatively assess how they change in response to neuronal triggers such as DBS.

To examine the effect of DBS on the hippocampus, Enikolopov teamed up with Andres Lozano, M.D., a leading Canadian neurosurgeon who pioneered its use against depression. The scientists found that stimulating the anterior thalamic nucleus—an area in the mouse brain that is equivalent to a human brain area where DBS is often therapeutically applied—resulted in an increase in cell division among the neural stem and progenitor cells, which in turn manifested as an increase in the number of new adult neurons in the hippocampus.

"By tracking new cell growth in the hippocampus and using it as a sensitive readout, we could potentially pinpoint other brain sites at which therapeutic DBS or other stimuli such as drugs might work best for various neurological and psychiatric conditions," explains Enikolopov.

INFORMATION:

"Neurogenic hippocampal targets of deep brain stimulation" appears in the January 1 issue of the Journal of Comparative Neurology. The full citation is: Juan M. Encinas, Clement Hamani, Andres M. Lozano, and Grigori Enikolopov. The paper is available online at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cne.22503/pdf.

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Founded in 1890, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has shaped contemporary biomedical research and education with programs in cancer, neuroscience, plant biology and quantitative biology. CSHL is ranked number one in the world by Thomson Reuters for impact of its research in molecular biology and genetics. The Laboratory has been home to eight Nobel Prize winners. Today, CSHL's multidisciplinary scientific community is more than 400 scientists strong and its Meetings & Courses program hosts more than 8,000 scientists from around the world each year. The Laboratory's education arm also includes a graduate school and programs for undergraduates as well as middle and high school students and teachers. CSHL is a private, not-for-profit institution on the north shore of Long Island. For more information, visit www.cshl.edu.

CSHL scientists identify elusive neuronal targets of deep brain stimulation

Study might provide new clues to designing better treatments for depression and other neuropsychiatric disorders

2010-12-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The ethics of biofuels

2010-12-15

In the world-wide race to develop energy sources that are seen as "green" because they are renewable and less greenhouse gas-intensive, sometimes the most basic questions remain unanswered.

In a paper released today by the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, authors Michal Moore, Senior Fellow, and Sarah M. Jordaan at Harvard University in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, look at the basic question of whether these energy sources are ethical.

In addition to arguing that the greenhouse gas benefits of biofuel are overstated by many policymakers, ...

Researchers discover new signaling pathway linked to inflammatory disease

2010-12-15

Scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have described for the first time a key inhibitory role for the IL-1 signaling pathway in the human innate immune system, providing novel insights into human inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and potential new treatments.

The research, led by Jose M. Gonzalez-Navajas, PhD, and Eyal Raz, MD, a professor of medicine at UC San Diego, is published as a Brief Definitive Report in the December issue of The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers report that signaling by the interleukin 1 receptor ...

Fighting flu in newborns begins in pregnancy

2010-12-15

A three-year study by Yale School of Medicine researchers has found that vaccinating pregnant women against influenza is over 90 percent effective in preventing their infants from being hospitalized with influenza in the first six months of life. Published in the December 15 issue of Clinical Infectious Diseases, the study builds on preliminary data the research team presented last year at the Infectious Disease Society of America in Philadelphia.

Influenza is a major cause of serious respiratory disease in pregnant women and of hospitalization in infants. Although the ...

Scripps scientists see the light in bizarre bioluminescent snail

2010-12-15

Two scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego have provided the first details about the mysterious flashes of dazzling bioluminescent light produced by a little-known sea snail.

Dimitri Deheyn and Nerida Wilson of Scripps Oceanography (Wilson is now at the Australian Museum in Sydney) studied a species of "clusterwink snail," a small marine snail typically found in tight clusters or groups at rocky shorelines. These snails were known to produce light, but the researchers discovered that rather than emitting a focused beam of light, the animal uses ...

Mothers' diets have biggest influence on children eating healthy

2010-12-15

EAST LANSING, Mich. — As health professionals search for ways to combat the rise in obesity and promote healthy eating, new research reveals a mother's own eating habits – and whether she views her child as a 'picky eater' – has a huge impact on whether her child consumes enough fruits and vegetables.

A study by professor Mildred Horodynski of Michigan State University's College of Nursing looked at nearly 400 low-income women (black and non-Hispanic white) with children ages 1-3 enrolled in Early Head Start programs. Results show toddlers were less likely to consume ...

IBEX makes first images of magnetotail structures, dynamic interactions occurring in space

2010-12-15

Invisible to the naked eye, yet massive in structure around the Earth is the magnetosphere, the region of space around the planet that ebbs and flows in response to the million-mile-per-hour flow of charged particles continually blasting from the Sun. NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) spacecraft, designed to image the invisible interactions occurring at the edge of the solar system, captured images of magnetospheric structures and a dynamic event occurring in the magnetosphere as the spacecraft observed from near lunar distance.

The data provides the first ...

UT researcher finds power and corruption may be good for society

2010-12-15

They are familiar scenes: politicians bemoaning the death of family values only for extramarital affairs to be unveiled or politicians preaching financial sacrifice while their expense accounts fatten up.

Moral corruption and power asymmetries are pervasive in human societies, but as it turns out, that may not be such a bad thing.

Francisco Úbeda, an evolutionary biology professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and Edgar Duéñez of Harvard University found that power and corruption may play a role in maintaining overall societal cooperation.

A report of ...

Y-90 radioembolization offers promise for late-stage liver cancer

2010-12-15

INDIANAPOLIS -- The latest weapon against inoperable liver cancer is so tiny that it takes millions of them per treatment, but according to interventional radiologists at the Indiana University School of Medicine, those microscopic spheres really pack a therapeutic punch.

The glass spheres contain a radioactive element, yttrium-90, more commonly known as Y-90, which emits radiation for a very limited distance so that healthy tissue around the tumor remains unaffected. (2.5mm or less than 1/16th inch in soft tissue).

Y-90 microsphere radioembolization is an FDA-approved ...

Tackling the erosion of a special river island

2010-12-15

Locke Island is a small island in a bend of the Columbia River in eastern Washington that plays a special role in the culture of the local Indian tribes. Since the 1970s, however, it has been eroding away at a rate that has alarmed tribal leaders.

The island is part of the Hanford Reservation, which is managed by the Department of Energy.

So the DOE has turned to a team of researchers headed by David Furbish, professor of earth and environmental sciences (E&ES) at Vanderbilt, to study the river dynamics in the area to identify the cause of the increase in erosion and ...

Ventilation changes could double number of lungs available for transplant: study

2010-12-15

TORONTO, Ont. 14, 2010—Simple changes to how ventilators are used could almost double the number of lungs available for transplants, according to new international research involving a doctor at St. Michael's Hospital.

Many potential donor lungs deteriorate between the time a patient is declared brain dead and the time the lungs are evaluated to determine whether they are suitable for transplant. The study involving Dr. Arthur Slutsky, the hospital's vice president of research, said the deterioration could be in part because of the ventilatory strategy used while potential ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

Maternal acetaminophen use and child neurodevelopment

Digital microsteps as scalable adjuncts for adults using GLP-1 receptor agonists

Researchers develop a biomimetic platform to enhance CAR T cell therapy against leukemia

Heart and metabolic risk factors more strongly linked to liver fibrosis in women than men, study finds

[Press-News.org] CSHL scientists identify elusive neuronal targets of deep brain stimulationStudy might provide new clues to designing better treatments for depression and other neuropsychiatric disorders