(Press-News.org) A new study using leading edge technology has shed surprising light on the ancient habitat where some of the first dinosaurs roamed in the UK around 200 million years ago.

The research, led by the University of Bristol, examined hundreds of pieces of old and new data including historic literature vividly describing the landscape as a "landscape of limestone islands like the Florida Everglades" swept by storms powerful enough to "scatter pebbles, roll fragments of marl, break bones and teeth."

The evidence was carefully compiled and digitised so it could be used to generate for the first time a 3D map showing the evolution of a Caribbean-style environment, which played host to small dinosaurs, lizard-like animals, and some of the first mammals.

"No one has ever gathered all this data before. It was often thought that these small dinosaurs and lizard-like animals lived in a desert landscape, but this provides the first standardised evidence supporting the theory that they lived alongside each other on flooded tropical islands," said Jack Lovegrove, lead author of the study published today in Journal of the Geological Society.

The study amassed all the data about the geological succession as measured all round Bristol through the last 200 years, from quarries, road sections, cliffs, and boreholes, and generated a 3D topographic model of the area to show the landscape before the Rhaetian flood, and through the next 5 million years as sea levels rose.

At the end of the Triassic period the UK was close to the Equator and enjoyed a warm Mediterranean climate. Sea levels were high, as a great sea, the Rhaetian Ocean, flooded most of the land. The Atlantic Ocean began to open up between Europe and North America causing the land level to fall. In the Bristol Channel area, sea levels were 100 metres higher than today.

High areas, such as the Mendip Hills, a ridge across the Clifton Downs in Bristol, and the hills of South Wales poked through the water, forming an archipelago of 20 to 30 islands. The islands were made from limestone which became fissured and cracked with rainfall, forming cave systems.

"The process was more complicated than simply drawing the ancient coastlines around the present-day 100-metre contour line because as sea levels rose, there was all kinds of small-scale faulting. The coastlines dropped in many places as sea levels rose," said Jack, who is studying Palaeontology and Evolution.

The findings have provided greater insight into the type of surroundings inhabited by the Thecodontosaurus, a small dinosaur the size of a medium-sized dog with a long tail also known as the Bristol dinosaur.

Co-author Professor Michael Benton, Professor of Vertebrate Palaeontology at the University of Bristol, said: "I was keen we did this work to try to resolve just what the ancient landscape looked like in the Late Triassic. The Thecodontosaurus lived on several of these islands including the one that cut across the Clifton Downs, and we wanted to understand the world it occupied and why the dinosaurs on different islands show some differences. Perhaps they couldn't swim too well."

"We also wanted to see whether these early island-dwellers showed any of the effects of island life," said co-author Dr David Whiteside, Research Associate at the University of Bristol.

"On islands today, middle-sized animals are often dwarfed because there are fewer resources, and we found that in the case of the Bristol archipelago. Also, we found evidence that the small islands were occupied by small numbers of species, whereas larger islands, such as the Mendip Island, could support many more."

The study, carried out with the British Geological Survey, demonstrates the level of detail that can be drawn from geological information using modern analytical tools. The new map even shows how the Mendip Island was flooded step-by-step, with sea level rising a few metres every million years, until it became nearly completely flooded 100 million years later, in the Cretaceous.

Co-author Dr Andy Newell, of the British Geological Survey, said: "It was great working on this project because 3D models of the Earth's crust can help us understand so much about the history of the landscape, and also where to find water resources. In the UK we have this rich resource of historical data from mining and other development, and we now have the computational tools to make complex, but accurate, models."

INFORMATION:

Paper

'Testing the relationship between marine transgression and evolving island palaeogeography using 3D GIS: an example from the Late Triassic of SW England' by Lovegrove, J., Newell, A.J., Whiteside, D.I., and Benton, M.J in Journal of the Geological Society

NEW YORK, NY (Feb. 26, 2021)--People who took statins to lower cholesterol were approximately 50% less likely to die if hospitalized for COVID-19, a study by physicians at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and NewYork-Presbyterian has found.

"Our study is one of the larger studies confirming this hypothesis and the data lay the groundwork for future randomized clinical trials that are needed to confirm the benefit of statins in COVID-19," says Aakriti Gupta, MD, a cardiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and one of the co-lead authors of the study.

"If their beneficial effect bears out in randomized clinical trials, statins could potentially prove to be a low-cost and effective therapeutic ...

Ithaca, NY--Famous for their uncanny ability to imitate other birds and even mechanical devices, researchers find that Australia's Superb Lyrebird also uses that skill in a totally unexpected way. Lyrebirds imitate the panicked alarm calls of a mixed-species flock of birds while males are courting and even while mating with a female. These findings are published in the journal Current Biology.

"The male Superb Lyrebird creates a remarkable acoustic illusion," says Anastasia Dalziell, currently a Cornell Lab of Ornithology Associate and recent Cornell Lab Rose Postdoctoral Fellow, now at the University of Wollongong, Australia. "Birds gather in mobbing flocks and the ruckus they make is a potent cue of a predator nearby. The ...

A common barnacle could be used to help trace missing persons lost at sea, according to research by UNSW Science.

Researchers from the Centre for Marine Science and Innovation have developed an equation that can estimate the minimum time an object has spent drifting at sea by counting the number of Lepas anserifera attached to the object.

They also developed an equation which can help plot possible drift paths of a missing boat.

"We saw this opportunity that Lepas could possibly fill in this gap in that marine forensic process and possibly contribute (to finding missing people)," study lead author Thomas ...

February 26, 2021 - Kawasaki, Japan: The Innovation Center of NanoMedicine (Director General: Prof. Kazunori Kataoka, Location: Kawasaki in Japan, Abbreviation: iCONM) reported in ACS Nano (Impact Factor: 14.588 in 2019) together with the group of Prof. Yu Matsumoto of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (Prof. Tatsuya Yamasoba) and the group of Prof. Horacio Cabral of the Department of Bioengineering (Prof. Ryo Miyake) in the University of Tokyo that the efficacy of polymeric nano-micelles with different drug activation profile depends on the expression level of c-Myc, one of the major proto-oncogene, has been developed. See: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.1c00364

It ...

Preterm labor comprises 12.7% of all pregnancies. Although the overall rate of pregnancy is decreasing, the occurrence of premature birth due to preterm labor in south korea has been increasing over the past 7 years. Not only is preterm birth accountable for about a half of all neonatal mortality cases, the neurological deficits in surviving premature infants often lead to problems later in life, such as developmental disorders and respiratory complications. Currently, preterm labor is detected only when expecting mothers experience abnormal symptoms, or when they undergo a routine test like abdominal ultrasound or a laboratory test for ...

Researchers at Oregon Health & Science University have demonstrated a new method of quickly mapping the genome of single cells, while also clarifying the spatial position of the cells within the body.

The discovery, published in the journal Nature Communications, builds upon previous advances by OHSU scientists in single-cell genome sequencing. The study represents another milestone in the field of precision medicine.

"It gives us a lot more precision," said senior author Andrew Adey, Ph.D., associate professor of molecular and medical genetics in the OHSU School of Medicine. "The single-cell aspect gives us the ability to track the molecular changes within each cell type. Our new study also allows the capture of where those ...

If you've ever watched Planet Earth, you know the ocean is a wild place to live. The water is teaming with different ecosystems and organisms varying in complexity from an erudite octopus to a sea star. Unexpectedly, it is the sea star, a simple organism characterized by a decentralized nervous system, that offers insights into advanced adaptation to hydrodynamic forces--the forces created by water pressure and flow.

Researchers from the USC Viterbi School of Engineering found that sea stars effectively stay attached to surfaces under extreme hydrodynamic loads by altering their shape. The researchers, including the Henry Salvatori Early Career Chair in Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering Mitul Luhar and doctoral ...

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological conditions, affecting more than 65 million worldwide. For those dealing with epilepsy, the advent of a seizure can feel like a ticking time bomb. It could happen at any time or any place, potentially posing a fatal risk when a seizure strikes during risky situations, such as while driving.

A research team at USC Viterbi School of Engineering and Keck Medicine of USC is tackling this dangerous problem with a powerful new seizure predicting mathematical model that will give epilepsy patients an accurate warning five minutes to one hour before they are likely to experience a seizure, offering enhanced freedom for the patient and cutting the need for medical intervention.

The research, ...

New York, NY (February 26, 2020) - Molecules called microRNAs (miRNAs) that are measurable in urine have been identified by researchers at Mount Sinai as predictors of both heart and kidney health in children without disease. The epidemiological study of Mexican children was published in February in the journal Epigenomics.

"For the first time, we measured in healthy children the associations between urinary miRNAs and cardiorenal outcomes, including blood pressure, urinary sodium and potassium levels, and eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate, a measure of how well the kidneys are filtering or cleaning the blood]," says lead author Yuri Levin-Schwartz, ...

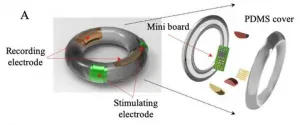

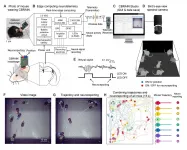

Living in a group has clear benefits. As a member of a societal group, one can share resources with the others, seek protection from predators, and forage in an efficient manner. In a 2020 paper published in Science Advances, the neuroscientist Jee Hyun Choi and her student Jisoo Kim of the Brain Science Institute in the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) argue that there are much more stories about the advantages of group living and social behaviors to the mammalian brain yet to be discovered. Their research was conducted using CBRAIN (Collective Brain Research Aided by Illuminating Neural activity), a unique neuro-telemetric device equipped with LED lights, which enables the ...