(Press-News.org) The Deepwater Horizon disaster began on April 20, 2010 with an explosion on a BP-operated oil drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico that killed 11 workers. Almost immediately, oil began spilling into the waters of the gulf, an environmental calamity that took months to bring under control, but not before it became the largest oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry.

Nearly 10 years have passed since then, and the oil slick has long since dispersed. Yet, despite early predictions, area wildlife are still feeling the effects of that oil, and research published in Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry has shown that negative health impacts have befallen not only dolphins alive at the time of the spill, but also in their young, born years later.

A team of researchers, including UConn Department of Pathobiology Professor and Director of the Connecticut Sea Grant College Program Sylvain De Guise, is part of a network conducting a long-term study on the health of bottlenose dolphins living in Louisiana's Barataria Bay, in the vicinity of the disaster. This population of dolphins includes individuals who lived through the disaster and some born afterwards.

"We were on the ready and as soon as we could, and in 2011 we initiated a comprehensive health assessment where 60 to 80 people in the field worked together to find and safely pursue a multi-disciplinary, multi-expertise sample collection and study effort to assess the dolphins' health," says De Guise.

De Guise explains that after collection, samples were processed in 60 to 80 different specialized labs, and the researchers then regrouped to put the information together. De Guise's research group specializes in studying the immune system, and from the very first set of samples they started to see consistent and abnormal immune responses in the Barataria Bay dolphins, compared with a similar control group of dolphins from Sarasota Bay who were not exposed to oil.

For the Barataria Bay dolphins, the researchers observed immune cells called T-cells that were overly responsive to stimulation. The body uses T-cells to respond to a stimulus, or something recognized as foreign. In particular, there were increased numbers of cells called regulatory T cells, or Tregs, which De Guise describes as the cells that help put the brakes on during an immune response to prevent the body from over-responding and doing more harm than good.

Despite the elevated numbers, De Guise says they were surprised to find the Barataria Bay dolphin Tregs appear to be functionally defective.

In some ways, the immune response can be looked at almost like a relay race, with cells signaling others to respond and join in the effort. In the case of T-helper (Th) cells, important signals called cytokines determine which type of T-helper will be next in the relay, and for the Barataria Bay dolphins, the signals are not relayed as expected.

"T-helper cells decide which direction your immune system will respond. If you have a pathogen that invades cells, a virus for example, you need a T-helper1 (Th1) response that will destroy the affected cells. If you have a pathogen that does not invade cells, like most types of bacteria, you need to generate antibodies to bind to those bacteria and help eliminate them with a Th2 response," says De Guise.

In the lab, the researchers studied the immune cells from both dolphin populations by exposing them to proteins called cytokines which elicit predictable responses from the T-cells. The researchers also exposed T-cells from the control group dolphins to oil to see what would happen. In all samples of T-cells exposed to oil, Th2 responses were exaggerated compared to the control group.

"We were able to demonstrate that there was a difference in responsiveness between the populations, in both real-life and in-vitro tests which resulted in an increase in Th2 response in the Barataria Bay dolphins," says De Guise.

The researchers went one step further by conducting a mouse study to see if a similar immune response could be seen in mice exposed to oil, and they did.

"The effects on the mouse immune system that we found were strikingly similar to what we saw in the dolphins," says De Guise. "We want to show the likelihood of a cause and effect relationship and add to the weight of evidence that oil impacts the immune system in a way that is very reproducible across species. The changes that we found in the Barataria Bay dolphins is specific to oil and not related to something else."

Though the researchers are not sure if the abnormal immune response is due to the initial exposure or continued exposure to oil still present in sediments, De Guise says the result may lead to the dolphins being more susceptible to pathogens like viruses, due to dysfunctional T-reg cells. Only future studies can shed light, and De Guise says now that images of oil slicks are no longer capturing attention, funding is harder to come by.

However, for this study, De Guise notes it is very rare to have such a long-term, detailed follow-up on a wild population of animals, and the researchers were very surprised to see effects in a second generation who did not live through the disaster.

"The outcome of this work is that we are not sure if these effects are reversible or not. The longer we look, they are still around. I think it is the first time we find such evidence across generations in a wild animal population, and that is scary. It raises concern for the long-term recovery of these dolphins," says De Guise. "These are long-lived mammals and, in many ways, not unlike humans who live in the area and depend on natural resources. It is interesting science, but it is very scary."

INFORMATION:

When central nervous system cells in the brain and spine are damaged by disease or injury, they fail to regenerate, limiting the body's ability to recover. In contrast, peripheral nerve cells that serve most other areas of the body are more able to regenerate. Scientists for decades have searched for molecular clues as to why axons -- the threadlike projections which allow communication between central nervous system cells -- cannot repair themselves after stroke, spinal cord damage, or traumatic brain injuries.

In a massive screen of 400 mouse genes, Yale School of Medicine ...

Disruptions in the circadian rhythms in lung cells may explain why adults who survived premature birth are often more at risk of severe influenza infections, suggests a study in mice published today in eLife.

Dramatic improvements in the care of infants born prematurely have allowed many more to survive into adulthood. Yet ex-preemies can face several long-term side effects of the life-saving care they received. The study suggests potential new approaches to treating lasting lung problems in those born prematurely.

Many premature infants are not able to breathe on their own and require oxygen to survive. ...

College course syllabi written in a warm, friendly tone are more likely to encourage students to reach out when they are struggling or need help, a new study from Oregon State University found.

Conversely, when a syllabus is written in a more cold, detached tone, students are less likely to reach out.

The study also compared the effect of syllabus tone with the effect of a deliberate "Reach out for help" statement included in the document.

"The instructor has to ask themselves, what's the first point of contact with the class for the student? In an online class and in remote learning, the syllabus is often the ...

The United States experiences more tornadoes than any other country, with a season that peaks in spring or summer depending on the region. Tornadoes are often deadly, especially in places where buildings can't withstand high winds.

Accurate advanced warnings can save lives. A study from the University of Washington and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration describes a new way to rate and possibly improve tornado warnings. It finds that nighttime twisters, summer tornadoes and smaller events remain the biggest challenges for the forecasting community.

"This new method lets us measure how forecast skill is improving, decreasing or staying the same in different situations," said Alex ...

A recent study of how human resources professionals review online information and social media profiles of job candidates highlights the ways in which so-called "cybervetting" can introduce bias and moral judgment into the hiring process.

"The study drives home that cybervetting is ultimately assessing each job candidate's moral character," says Steve McDonald, corresponding author of the study and a professor of sociology at North Carolina State University. "It is equally clear that many of the things hiring professionals are looking at make it more likely for ...

p>

Boulder, Colo., USA: Several new articles were published online ahead of

print for Geology in February. Topics include stress in survivor

plants following the collapse of land ecosystems, the Gulf of Aden, whether

the Denali fault is still active, the first reported Burgess Shale-type

fauna rediscovered, and redefining the age of the lower Colorado River.

These Geology articles are online at END ...

Researchers from Skoltech's Intelligent Space Robotics Lab have proposed a novel method for customer behavior analytics and demand distribution based on Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) stocktaking. Their research was published in the proceedings of the International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV).

Autonomous robotic systems that already pervade our daily lives are faced with a host of challenging tasks, such as stocktaking in a rapidly changing environment.

A Skoltech team led by Professor Dzmitry Tsetserukou from the Skoltech Space Center (Intelligent Space Robotics Lab) has proposed a novel method that helps ...

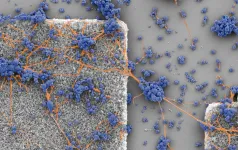

EUGENE, Ore. - March 2, 2021 - High-resolution imaging and 3D computer modeling show that the dendrites of neurons weave through space in a way that balances their need to connect to other neurons with the costs of doing so.

The discovery, reported in Nature Scientific Reports Jan. 27, emerged as researchers sought to understand the fractal nature of neurons as part of a University of Oregon project to design fractal-shaped electrodes to connect with retinal neurons to address vision loss due to retinal diseases.

"The challenge in our research has been understanding how the neurons we want to target in the retina will connect to our electrodes," said Richard Taylor, a professor and head ...

An analysis of law enforcement seizures of illegal drugs in five key regions of the United States revealed a rise in methamphetamine and marijuana (cannabis) confiscations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Seizures of the two drugs were higher at their peak in August 2020 than at any time in the year prior to the pandemic. While investigators found that trends in heroin, cocaine and fentanyl seizures were not affected by the pandemic, provisional overdose death data show that the increased drug mortality seen in 2019 rose further through the first half of 2020.

The findings suggest that the pandemic and its related restrictions may ...

Washington, DC-- March 2, 2021 -- Detecting COVID-19 outbreaks before they spread could help contain the virus and curb new cases within a community. This week in mSystems, an open-access Journal of the American Society for Microbiology, researchers from the University of California San Diego describe a mostly-automated early alert system that uses high-throughput analysis of wastewater samples to identify buildings where new COVID-19 cases have emerged--even before infected people develop symptoms.

The approach is fast, cost-effective, and sensitive enough to detect a single ...