(Press-News.org) Researchers from Bremen, together with their colleagues from the Max Planck Genome Center in Cologne and the aquatic research institute Eawag from Switzerland, have discovered a unique bacterium that lives inside a unicellular eukaryote and provides it with energy. Unlike mitochondria, this so-called endosymbiont derives energy from the respiration of nitrate, not oxygen. "Such partnership is completely new," says Jana Milucka, the senior author on the Nature. "A symbiosis that is based on respiration and transfer of energy is to this date unprecedented".

In general, among eukaryotes, symbioses are rather common. Eukaryotic hosts often co-exist with other organisms, such as bacteria. Some of the bacteria live inside the host cells or tissue, and perform certain services, such defense or nutrition. In return, the host provides shelter and suitable living conditions for the symbiont. An endosymbiosis can even go that far that the bacterium loses its ability to survive on its own outside its host.

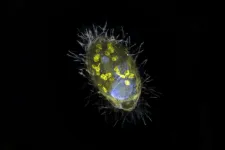

This was also the case with the symbiosis discovered by the Bremen scientists in Lake Zug in Switzerland. "Our finding opens the possibility that simple unicellular eukaryotes, such as protists, can host energy-providing endosymbionts to complement or even replace the functions of their mitochondria," says Jon Graf, first author of the study. "This protist has managed to survive without oxygen by teaming up with an endosymbiont capable of nitrate respiration." The endosymbiont's name 'Candidatus Azoamicus ciliaticola' reflects this; a 'nitrogen friend' that dwells within a ciliate.

An intimate partnership becomes ever closer

So far, it has been assumed that eukaryotes in oxygen-free environments survive through fermentation, since mitochondria require oxygen in order to generate energy. The fermentation process is well documented and has been observed in many anaerobic ciliates. However, microorganisms cannot draw as much energy from fermentation, and they typically do not grow and divide as quickly as their aerobic counterparts.

"Our ciliate has found a solution for this," says Graf. "It has engulfed a bacterium with the ability to breathe nitrate and integrated it into its cell. We estimate that the assimilation took place at least 200 to 300 million years ago". Since then, evolution has further deepened this intimate partnership.

Time-shifted evolution

The evolution of mitochondria has proceeded in a similar way. „All mitochondria have a common origin," explains Jana Milucka. It is believed that more than a billion years ago when an ancestral archaeon engulfed a bacterium, these two started a very important symbiosis: this event marked the origin of the eukaryotic cell. Over time, the bacterium became more and more integrated into the cell, progressively reducing its genome. Properties no longer needed were lost and only the ones that benefitted the host were retained. Eventually, mitochondria evolved, as we know them today. They have their own tiny genome as well as a cell membrane, and exist as so-called organelles in eukaryotes. In the human body, for example, they are present in almost every cell and supply them - and thus us - with energy.

"Our endosymbiont is capable of performing many mitochondrial functions, even though it does not share a common evolutionary origin with mitochondria," says Milucka. "It is tempting to speculate that the symbiont might follow the same path as mitochondria, and eventually become an organelle".

A chance encounter

It is actually amazing that this symbiosis has remained unknown for so long. Mitochondria work so well with oxygen - why shouldn't there be an equivalent for nitrate? One possible answer is that no one was aware of this possibility and so no one was looking for it. Studying endosymbioses is challenging, as most symbiotic microorganisms cannot be grown in the laboratory. However, the recent advances in metagenomic analyses have allowed us to gain a better insight into the complex interaction between hosts and symbionts. When analyzing a metagenome, scientists look at all genes in a sample. This approach is often used for environmental samples as the genes in a sample cannot be automatically assigned to the organisms present. This means that scientists usually look for specific gene sequences that are relevant to their research question. Metagenomes often contain millions of different gene sequences and it is quite normal that only a small fraction of them is analyzed in detail.

Originally, the Bremen scientists were also looking for something else. The Research Group Greenhouse Gases at the Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology investigates microorganisms involved in methane metabolism. For this, they have been studying the deep-water layers of Lake Zug. The lake is highly stratified, which means that there is no vertical exchange of water. The deep-water layers of Lake Zug thus have no contact with surface water and are largely isolated. That is why they contain no oxygen but are rich in methane and nitrogen compounds, such as nitrate. While looking for methane munching bacteria with genes for nitrogen conversion, Graf came across an amazingly small gene sequence that encoded the complete metabolic pathway for nitrate respiration. "We were all stunned by this finding and I started comparing the DNA with similar gene sequences in a database," says Graf. But the only similar DNA belonged to that of symbionts that live in aphids and other insects. "This didn't make sense. How would insects get into these deep waters? And why?," Graf remembers. The scientists of the research group started guessing games and betting.

Not alone in the dark lake

In the end, one thought prevailed: The genome must belong to a yet-unknown endosymbiont. To verify this theory, members of the research team undertook several expeditions to Lake Zug in Switzerland. With the help of the local cooperation partner Eawag they collected samples to look specifically for the organism that contains this unique endosymbiont. In the lab, the scientists fished out various eukaryotes out of the water samples with a pipette. At last, using a gene marker, it was possible to visualize the endosymbiont and identify its protist host.

A final excursion one year ago was supposed to bring final certainty. It was a difficult undertaking in the middle of winter. Stormy weather, dense fog and time pressure due to first news about Coronavirus as well as a possible lockdown made the search in the big lake even more difficult. Nonetheless, the scientists succeeded in retrieving several samples from the deep water and bringing them to Bremen. These samples brought them final confirmation of their theory. "It is nice knowing that they are down there together," says Jana Milucka. "Normally, these ciliates eat bacteria. But this one let one alive and partnered up with it".

Many new questions

This finding provokes many exciting new questions. Are there similar symbioses that have existed much longer and where the endosymbiont has already crossed the boundary to an organelle? If such symbiosis exists for nitrate respiration, does it also exist for other compounds? How did this symbiosis, which has existed since 200 to 300 million years, end up in a post-glacial lake in the Alps that only formed 10,000 years ago? Moreover: "Now that we know what we are looking for, we found the endosymbiont's gene sequences all around the world," says Milucka. In France, as well as in Taiwan, or in East African lakes that in part are much older than Lake Zug. Does the origin of this symbiosis lie in one of them? Or did it start in the ocean? These are the questions that the research group wants to investigate next.

INFORMATION:

An international research group led by the University of Basel has developed a promising strategy for therapeutic cancer vaccines. Using two different viruses as vehicles, they administered specific tumor components in experiments on mice with cancer in order to stimulate their immune system to attack the tumor. The approach is now being tested in clinical studies.

Making use of the immune system as an ally in the fight against cancer forms the basis of a wide range of modern cancer therapies. One of these is therapeutic cancer vaccination: following diagnosis, specialists set about determining which components of the tumor could function as an identifying feature for the immune system. The patient is then administered ...

The universe was created by a giant bang; the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, and then it started to expand. The expansion is ongoing: it is still being stretched out in all directions like a balloon being inflated.

Physicists agree on this much, but something is wrong. Measuring the expansion rate of the universe in different ways leads to different results.

So, is something wrong with the methods of measurement? Or is something going on in the universe that physicists have not yet discovered and therefore have not taken into account?

It could very well be the latter, according to several physicists, i.a. Martin S. Sloth, Professor of Cosmology at University of Southern Denmark (SDU).

In a new scientific article, he and his SDU ...

A new software tool allows researchers to quickly query datasets generated from single-cell sequencing. Users can identify which cell types any combination of genes are active in. Published in Nature Methods on 1st March, the open-access 'scfind' software enables swift analysis of multiple datasets containing millions of cells by a wide range of users, on a standard computer.

Processing times for such datasets are just a few seconds, saving time and computing costs. The tool, developed by researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, can be used much like a search engine, as users can input free text as well as gene names.

Techniques to sequence the genetic material from an individual cell have advanced ...

Information is encoded in data. This is true for most aspects of modern everyday life, but it is also true in most branches of contemporary physics, and extracting useful and meaningful information from very large data sets is a key mission for many physicists.

In statistical mechanics, large data sets are daily business. A classic example is the partition function, a complex mathematical object that describes physical systems at equilibrium. This mathematical object can be seen as made up by many points, each describing a degree of freedom of a physical system, that is, the minimum number of data that can describe all of its properties.

An ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Boron, a metalloid element that sits next to carbon in the periodic table, has many traits that make it potentially useful as a drug component. Nonetheless, only five FDA-approved drugs contain boron, largely because molecules that contain boron are unstable in the presence of molecular oxygen.

MIT chemists have now designed a boron-containing chemical group that is 10,000 times more stable than its predecessors. This could make it possible to incorporate boron into drugs and potentially improve the drugs' ability to bind their targets, the researchers say.

"It's an entity ...

Judging by its massive, bone-crushing teeth, gigantic skull and powerful jaw, there is no doubt that the Anteosaurus, a premammalian reptile that roamed the African continent 265 to 260 million years ago - during a period known as the middle Permian - was a ferocious carnivore.

However, while it was previously thought that this beast of a creature - that grew to about the size of an adult hippo or rhino, and featuring a thick crocodilian tail - was too heavy and sluggish to be an effective hunter, a new study has shown that the Anteosaurus would have been able to outrun, track down and kill its prey effectively.

Despite its name and fierce appearance, ...

When the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland erupted in April 2010, air traffic was interrupted for six days and then disrupted until May. Until then, models from the nine Volcanic Ash Advisory Centres (VAACs) around the world, which aimed at predicting when the ash cloud interfered with aircraft routes, were based on the tracking of the clouds in the atmosphere. In the wake of this economic disaster for airlines, ash concentration thresholds were introduced in Europe which are used by the airline industry when making decisions on flight restrictions. However, a team of researchers, ...

The planet Mars has no global magnetic field, although scientists believe it did have one at some point in the past. Previous studies suggest that when Mars' global magnetic field was present, it was approximately the same strength as Earth's current field. Surprisingly, instruments from past Mars missions, both orbiters and landers, have spotted patches on the planet's surface that are strongly magnetized--a property that could not have been produced by a magnetic field similar to Earth's, assuming the rocks on both planets are similar.

Ahmed AlHantoobi, an intern working with Northern Arizona University planetary scientists, assistant professor Christopher Edwards and postdoctoral ...

PITTSBURGH, March 3, 2021 - Women who experience an accelerated accumulation of abdominal fat during menopause are at greater risk of heart disease, even if their weight stays steady, according to a University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health-led analysis published today in the journal Menopause.

The study--based on a quarter century of data collected on hundreds of women--suggests that measuring waist circumference during preventive health care appointments for midlife women could be an early indicator of heart disease risk beyond the widely used body mass index (BMI)--which is a calculation of weight vs. height.

"We need to shift gears on how we think about heart disease risk in women, particularly as they approach and go through menopause," said senior ...

A review of nearly 28,000 emergency department records shows less than 2% of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 suffered an ischemic stroke but those who did had an increased risk of requiring long-term care after hospital discharge. Those are the findings from a study conducted by researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine and MU Health Care.

The researchers teamed up with the MU Institute for Data Science and Informatics and the Tiger Institute for Health Innovation to review data from 54 health care facilities. They found 103 patients (1.3%) developed ischemic stroke among 8,163 patients with COVID-19. ...