The ubiquitous p53 protein in its natural state, sometimes called "the guardian of the genome," is a front-line protector against cancer. But the mutant form appears in 50% or more of human cancers and actively blocks cancer suppressors.

Researchers led by Peter Vekilov at the University of Houston (UH) and Anatoly Kolomeisky at Rice University have discovered the same mutant protein can aggregate into clusters. These in turn nucleate the formation of amyloid fibrils, a prime suspect in cancers as well as neurological diseases like Alzheimer's.

The condensation of p53 into clusters is driven by the destabilization of the protein's DNA-binding pocket when a single arginine amino acid is replaced with glutamine, they reported.

"It's known that a mutation in this protein is a main source of cancer, but the mechanism is still unknown," said Kolomeisky, a professor and chair of Rice's Department of Chemistry and a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

"This knowledge gap has significantly constrained attempts to control aggregation and suggest novel cancer treatments," said Vekilov, the John and Rebecca Moores Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and Chemistry at UH.

The mutant p53 clusters, which resemble those discovered by Vekilov in solutions of other proteins 15 years ago, and the amyloid fibrils they nucleate prompt the aggregation of proteins the body uses to suppress cancer. "This is similar to what happens in the brain in neurological disorders, though those are very different diseases," Kolomeisky said.

The p53 mechanism described in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences may be similar to those that form functional and pathological solids like tubules, filaments, sickle cell polymers, amyloids and crystals, Vekilov said.

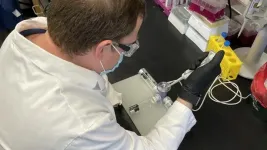

Researchers at UH combined 3D confocal images of breast cancer cells taken in the lab of chemical and biomolecular engineer Navin Varadarajan with light scattering and optical microscopy of solutions of the purified protein carried out in the Vekilov lab.

Transmission electron microscopy micrographs of cluster and fibril formation contributed by Michael Sherman at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB) supported the main result of the study, as did molecular simulations by Kolomeisky's group

All confirmed the p53 mutant known as R248Q goes through a two-step process to form mesoscopic condensates. Understanding the mechanism could provide insight into treating various cancers that manipulate either p53 or its associated signaling pathways, Vekilov said.

In normal cell conditions, the concentration of p53 is relatively low, so the probability of aggregation is low, he said. But when a mutated p53 is present, the probability increases.

"Experiments show the size of these clusters is independent of the concentration of p53," Kolomeisky said. "Mutated p53 will even take normal p53 into the aggregates. That's one of the reasons for the phenomenon known as loss of function."

If even a small relative fraction of the mutant is present, it's enough to kill or lower the ability of normal, wild-type p53 to fight cancer, according to the researchers.

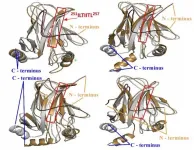

The Rice simulations showed normal p53 proteins are compact and easily bind to DNA. "But the mutants have a more open conformation that allows them to interact with other proteins and gives them a higher tendency to produce a condensate," Kolomeisky said. "It's possible that future anti-cancer drugs will target the mutants in a way that suppresses the formation of these aggregates and allows wild-type p53 to do its job."

INFORMATION:

UH graduate student David Yang is lead author of the paper. Co-authors are Rice graduate student Alena Klindziuk and alumnus Aram Davtyan; UH graduate student Arash Saeedi and alumni Mohsen Fathi and Mohammad Safari; and Michelle Barton, a former professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center now at Oregon Health & Science University. Varadarajan is the MD Anderson Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at UH. Sherman is an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at UTMB.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, the Melanoma Research Alliance, NASA, Rice's Center for Theoretical Biological Physics and the Sealy Center for Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics at UTMB.

Read the abstract at https://www.pnas.org/content/118/10/e2015618118.

This news release can be found online at https://news.rice.edu/2021/03/04/cancer-guardian-breaks-bad-with-one-switch/

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Kolomeisky Research Group: http://python.rice.edu/~kolomeisky/

Vekilov Research Group: https://vekilovgroup.chee.uh.edu

Image for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/03/0308_AMYLOID-1-web.jpg

A model produced by scientists at Rice University shows the conformational changes caused by a mutation in the cancer-fighting p53 protein. At top left, the red box highlights the aggregation-prone sequence protected by the N-terminus tail in wild-type p53 but exposed by the mutation of a single amino acid. The strongest deviation happens in the domain at the green asterisk. The other three models show "open" conformations at the C-terminus caused by the mutation. (Credit: Kolomeisky Research Group/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,978 undergraduates and 3,192 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

AT RICE:

Jeff Falk

713-348-6775

jfalk@rice.edu

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON:

Stephen Greenwell

401-430-0476

sjgreen2@central.uh.edu