Wider horizons for highly ordered nanohole arrays

More transition metals available to make ordered porous metallic oxide thin films

2021-03-13

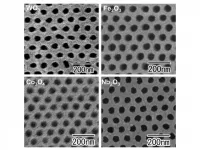

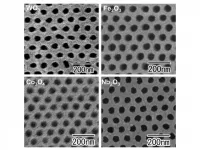

(Press-News.org) Tokyo, Japan - Scientists from Tokyo Metropolitan University have developed a new method for making ordered arrays of nanoholes in metallic oxide thin films using a range of transition metals. The team used a template to pre-pattern metallic surfaces with an ordered array of dimples before applying electrochemistry to selectively grow an oxide layer with holes. The process makes a wider selection of ordered transition metal nanohole arrays available for new catalysis, filtration, and sensing applications.

A key challenge of nanotechnology is getting control over the structure of materials at the nanoscale. In the search for materials that are porous at this length scale, the field of electrochemistry offers a particularly elegant strategy: anodization using metallic electrodes, particularly aluminum and titanium, can be used to form ordered arrays of "nanoholes" in a metallic oxide layer. By getting the conditions right, these holes adopt highly ordered patterns, with tight control over their spacing and size. These ordered porous metallic oxide films are ideal for a wide range of industrial applications, such as filtration and efficient catalysis. But to get them out of the lab and into widespread use, production methods need to become more scalable and compatible with a wider range of materials.

Enter a team led by Prof. Takashi Yanagishita of Tokyo Metropolitan University who have been pushing the boundaries of ordered nanohole array fabrication. In previous work, they developed a scalable method to make ordered nanohole arrays in aluminum oxide thin films. The team's films could be made up to 70 mm in diameter, and easily detached from the substrates they are made on. Now, they have used these films to create similar patterns using a far wider range of transition metal oxides. By using the ordered nanoporous alumina as a mask, they used argon ion milling to etch ordered arrays of shallow dimples in the surfaces of various transition metals, including tungsten, iron, cobalt and niobium. Then by anodizing the dimpled surfaces, they found that thin metallic oxide layers formed with holes where the dimples were. Previous efforts had indeed made nanoscale holes in e.g. tungsten oxide films, but the holes were not ordered, with little control over their size or spacing, making this the first time ordered nanohole arrays have been made using these transition metal oxides. On top of that, by changing the properties of the mask, they directly demonstrated how they could easily tune the spacing between the holes, making their method applicable to a wide range of nanoporous patterns with different applications.

Exciting applications are waiting for these nanostructured films, including photocatalysis, sensing applications and solar cells. The team are confident that their new scalable, tunable method for making ordered nanohole arrays with freer choice of materials will help boost efforts to bring this exciting field of nanotechnology out of the lab, and into the wider world.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by a JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid of Scientific Research, Grant Number JP20K05171.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-13

MRI scanning can more precisely define and detect head, neck, thoracic, abdominal and spinal malformations in unborn babies, finds a large multidisciplinary study led by King's College London with Evelina London Children's Hospital, Great Ormond Street Hospital and UCL.

In the study, published today in Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, the team of researchers and clinicians demonstrate the ways that MRI scanning can show malformations in great detail, including their effect on surrounding structures. Importantly, they note that MRI is a very safe procedure for pregnant women and their babies.

They say the work is invaluable both to clinicians caring for babies before they are born and for teams planning care of the baby after delivery.

Recent research has concentrated ...

2021-03-12

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) dramatically increased children's preventive healthcare while reducing out-of-pocket costs, according to a new Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) study.

Published in JAMA Network Open, the study found that checkups with out-of-pocket costs dropped from 54.2% of visits in 2010 (the year the ACA passed) to 14.5% in 2018.

"This is a great feather in the cap of the ACA, even though there is still some work to do," says study lead author Dr. Paul Shafer, assistant professor of health law, policy & management at BUSPH.

"We found ...

2021-03-12

MIAMI--A new study lead by scientists at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science demonstrates that under realistic environmental conditions oil drifting in the ocean after the DWH oil spill photooxidized into persistent compounds within hours to days, instead over long periods of time as was thought during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. This is the first model results to support the new paradigm of photooxidation that emerged from laboratory research.

After an oil spill, oil droplets on the ocean surface ...

2021-03-12

Cancer cells can dodge chemotherapy by entering a state that bears similarity to certain kinds of senescence, a type of "active hibernation" that enables them to weather the stress induced by aggressive treatments aimed at destroying them, according to a new study by scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine. These findings have implications for developing new drug combinations that could block senescence and make chemotherapy more effective.

In a study published Jan. 26 in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, the investigators reported that this biologic process could help explain why cancers so often recur after treatment. The research was done in both organoids and mouse models ...

2021-03-12

A study of the relationship between temperature and yields of various rice varieties, based on 50 years of weather and rice-yield data from farms in the Philippines, suggests that warming temperatures negatively affect rice yields.

Recent varieties of rice, bred for environmental stresses like heat, showed better yields than both traditional rice varieties and modern varieties of rice that were not specifically bred to withstand warmer temperatures. But the study found that warming adversely affected crop yields even for those varieties best suited to the heat. Overall, the advantage of varieties bred to withstand increased heat was too small to be statistically significant.

One of ...

2021-03-12

Intake of a high-fat diet leads to an increased risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and fatty liver. A study in mice from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that it is possible to eliminate the deleterious effects of a high-fat diet by lowering the levels of apolipoprotein CIII (apoCIII), a key regulator of lipid metabolism. The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

Increased levels of the protein apoCIII are related to cardiovascular diseases, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Researchers at the Rolf Luft Research ...

2021-03-12

New research led by the University of Cambridge has found rare evidence - preserved in the chemistry of ancient rocks from Greenland - which tells of a time when Earth was almost entirely molten.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, yields information on a important period in our planet's formation, when a deep sea of incandescent magma stretched across Earth's surface and extended hundreds of kilometres into its interior.

It is the gradual cooling and crystallisation of this 'magma ocean' that set the chemistry of Earth's interior - a defining stage in the assembly of our planet's structure and the formation of our early atmosphere.

Scientists know that catastrophic impacts during the formation of the Earth and Moon would have generated ...

2021-03-12

As the driver of global atmospheric and ocean circulation, the tropics play a central role in understanding past and future climate change. Both global climate simulations and worldwide ocean temperature reconstructions indicate that the cooling in the tropics during the last cold period, which began about 115,000 years ago, was much weaker than in the temperate zone and the polar regions. The extent to which this general statement also applies to the tropical high mountains of Eastern Africa and elsewhere is, however, doubted on the basis of palaeoclimatic, geological and ecological studies at high elevations.

A research team led by Alexander Groos, Heinz Veit (both from the Institute of Geography) and Naki Akçar (Institute of Geological Sciences) at the University ...

2021-03-12

How much did SARS-CoV-2 need to change in order to adapt to its new human host? In a research article published in the open access journal PLOS Biology Oscar MacLean, Spyros Lytras at the University of Glasgow, and colleagues, show that since December 2019 and for the first 11 months of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic there has been very little 'important' genetic change observed in the hundreds of thousands of sequenced virus genomes.

The study is a collaboration between researchers in the UK, US and Belgium. The lead authors Prof David L Robertson (at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, Scotland) ...

2021-03-12

Informing how COVID-19 response plans may incorporate digital contact tracing, a model of COVID-19 spread within a simulated French population found that if about 20% of the population adopted a contact tracing app on their smartphones, an outbreak could be reduced by about 35%. If more than 30% of the population adopted the app, the epidemic could be suppressed to manageable levels. Jesús Moreno López and colleagues note that the effectiveness of digital contact tracing would depend on a given population's level of immunity to the virus; the intervention alone would be unable to suppress a COVID-19 epidemic where transmission - and especially asymptomatic transmission - remains high. While many countries have implemented ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Wider horizons for highly ordered nanohole arrays

More transition metals available to make ordered porous metallic oxide thin films