(Press-News.org) Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute demonstrated for the first time that blocking "cell drinking," or macropinocytosis, in the thick tissue surrounding a pancreatic tumor slowed tumor growth--providing more evidence that macropinocytosis is a driver of pancreatic cancer growth and is an important therapeutic target. The study was published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"Now that we know that macropinocytosis is 'revved up' in both pancreatic cancer cells and the surrounding fibrotic tissue, blocking the process might provide a 'double whammy' to pancreatic tumors," says Cosimo Commisso, Ph.D., associate professor and co-director of the Cell and Molecular Biology of Cancer Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys and senior author of the study. "Our lab is investigating several drug candidates that inhibit macropinocytosis, and this study provides the rationale that they should be advanced as quickly as possible."

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the deadliest cancers. Only one in ten people survive longer than five years, according to the American Cancer Society, and its incidence is on the rise. Pancreatic cancer is predicted to become the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the U.S. by 2030.

"If we want to create a world in which all people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer will thrive, we first need to understand the key drivers of tumor growth," says Lynn Matrisian, Ph.D., chief science officer at the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN), who wasn't involved in the study. "This study suggests that macropinocytosis is an important target for drug development, and that progressing this novel treatment approach may help more people survive pancreatic cancer."

Starving the stroma

Pancreatic tumors are surrounded by an unusually thick layer of stroma, or glue-like connective tissue that holds cells together. This stromal barrier makes it difficult for treatments to reach the tumor, and fuels tumor growth by providing the tumor with nutrients. Commisso's previous research showed that rapidly growing pancreatic tumors obtain nutrients through macropinocytosis, an alternative route that normal cells don't use--and he wondered if macropinocytosis in the stroma may also fuel tumor growth.

To test this hypothesis, Commisso and his team blocked macropinocytosis in cells that surround and nourish pancreatic tumors, called pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and co-transplanted the modified cells with pancreatic tumor cells into mice. The scientists found that tumor growth slowed in these mice--compared to control groups in which macropinocytosis remained active in the stroma--suggesting that the approach holds promise as a way to treat pancreatic cancer.

"We are excited about this approach because instead of removing the stroma, which can cause the tumor to spread throughout the body, we simply block the process that is driving tumor growth," says Yijuan Zhang, Ph.D., postdoctoral researcher in the Commisso lab and first author of the study. "We also deciphered the molecular signals that drive macropinocytosis in the stroma, providing new therapeutic avenues for pancreatic cancer researchers to explore."

Promising drug targets identified

Based on their ongoing macropinocytosis research, the scientists have identified many druggable targets that may inhibit the process. Bolstered by this study's findings, they will continue to investigate the promise of drug candidates that inhibit macropinocytosis as potential pancreatic cancer treatments.

"We already knew that macropinocytosis was a very important growth driver for pancreatic cancer, as well as lung, prostate, bladder and colon tumors," says Commisso. "This study further spurs our efforts to advance a drug that targets macropinocytosis, which may be the breakthrough we need to finally put an end to many deadly and devastating cancers."

INFORMATION:

Additional study authors include Victoria Recouvreux, Michael Jung, Koen M.O. Galenkamp, Olga Zagnitko, David A. Scott of Sanford Burnham Prebys; Yunbo Li and Andrew M. Lowy of University of California, San Diego.

The study's DOI is 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0119.

Research reported in this press release was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (CA207189, CA211036 and P30CA030199).

About Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Research Institute

Sanford Burnham Prebys is a preeminent, independent biomedical research institute dedicated to understanding human biology and disease and advancing scientific discoveries to profoundly impact human health. For more than 40 years, our research has produced breakthroughs in cancer, neuroscience, immunology and children's diseases, and is anchored by our NCI-designated Cancer Center and advanced drug discovery capabilities. For more information, visit us at SBPdiscovery.org or on Facebook at facebook.com/SBPdiscovery and on Twitter @SBPdiscovery.

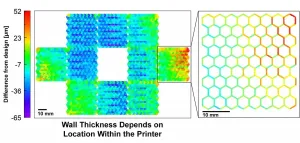

Researchers at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign developed software to improve the accuracy of 3D-printed parts, seeking to reduce costs and waste for companies using additive manufacturing to mass produce parts in factories.

"Additive manufacturing is incredibly exciting and offers tremendous benefits, but consistency and accuracy on mass-produced 3D-printed parts can be an issue. As with any production technology, parts built should be as close to identical as possible, whether it is 10 parts or 10 million," said Professor Bill King, Andersen Chair in the Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering and leader of the project.

The team's ...

- The increasing complexity of treatments for lung cancer and language differences can make it difficult for patients to communicate with their medical teams

- Risks of jeopardising the treatment and care journey as well as recent progress in patient empowerment.

Lugano, Switzerland; Denver, CO, USA, 17 March 2021 - More than one in 10 patients with lung cancer do not know what type of tumour they have, according to data from a 17-country study carried out by the Global Lung Cancer Coalition (GLCC) to be presented at the European Lung Cancer Conference (ELCC) ...

What would a volcano - and its lava flows - look like on a planetary body made primarily of metal? A pilot study from North Carolina State University offers insights into ferrovolcanism that could help scientists interpret landscape features on other worlds.

Volcanoes form when magma, which consists of the partially molten solids beneath a planet's surface, erupts. On Earth, that magma is mostly molten rock, composed largely of silica. But not every planetary body is made of rock - some can be primarily icy or even metallic.

"Cryovolcanism is volcanic activity on icy worlds, and we've seen it happen on Saturn's moon Enceladus," says Arianna Soldati, assistant professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences at NC State and lead author of a paper describing the ...

TORONTO, ON - American adults 65 years old and older have better vision than that age group did nearly a decade ago, according to a recent study published in the journal Ophthalmic Epidemiology.

In 2008, 8.3% of those aged 65 and older in the US reported serious vision impairment. In 2017 that number decreased to 6.6% for the 65-plus cohort. Put another way: if vision impairment rates had remained at 2008 levels, an additional 848,000 older Americans would have suffered serious vision impairment in 2017.

"The implications of a reduction in vision impairment are significant," ...

Cancer develops when changes occur with one or more genes in our cells. A change in a gene is called a fault or a mutation.

The inherited gene mutations found in this study, are passed from parent to child and are common in the population. However, each one individually does not significantly raise cancer risk.

Instead, these mutations collectively act to raise the risk of cancer developing. They do not directly cause cancer, instead they most likely interact with many other risk factors or random mutations that accumulate over a person's lifetime.

Cancers caused by inherited faulty genes were previously thought to be very rare, compared with mutations that happen by chance as we ...

Fields and farms with more variety of insect pollinator species provide more stable pollination services to nearby crops year on year, according to the first study of its kind.

An international team of scientists led by the University of Reading carried out the first ever study of pollinator species stability over multiple years across locations all around the world, to investigate how to reduce fluctuations in crop pollination over time.

They found areas with diverse communities of pollinators, and areas with stable populations of dominant species, suffered fewer year-to-year fluctuations ...

Living for nearly 2 months in simulated weightlessness has a modest but widespread negative effect on cognitive performance that may not be counteracted by short periods of artificial gravity, finds a new study published in END ...

Scleritis is a vision-threatening inflammatory condition of the white portion of the eye, or the sclera, that is thought to be the result of an over-reaction of the body's immune system. A new study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology provides estimates of the incidence and prevalence of scleritis between 1997 and 2018 in the U.K.

Investigators found that the U.K. incidence of new cases appears to have fallen by about one-third over the past 22 years, to 2.8 new cases per 100,000 people per year. This trend is likely due to improvements in the management of immune-related diseases. Individuals who developed scleritis often ...

Fractures in the vertebrae of the spine and calcification in a blood vessel called the abdominal aorta can both be visualized through the same spinal imaging test. A new study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research that included 5,365 older men indicates that each of these measures are linked with a higher risk of developing hip and other fractures.

Investigators found that including both measures compared with including only abdominal aortic calcification or only vertebral fractures improved the ability to predict which men were most likely to experience a hip or other fracture in the future.

"Both abdominal aortic calcification ...

While play and playfulness have been studied well in children, their structure and consequences are understudied in adults. A new article published in Social and Personality Psychology Compass highlights available research on this topic and also examines why playfulness is important in romantic relationships.

The authors note that playfulness encourages the experience of positive emotions and might relate to potential biological processes--such as the activation of hormones and certain brain circuits. It also influences how people communicate and interact with each other, for example by helping to deal with stress, and solving interpersonal tension. These can all impact relationship ...