Elusive protein complex could hold the key to treating chromosomal disorders

Scientists report on the structural and molecular factors governing the stability of a protein complex involved in DNA repair pathways in cells

2021-03-17

(Press-News.org) One of the most vital functions performed by the cells in our body is DNA repair, a task so crucial to our well-being that failing to execute it can lead to consequences as dreadful as cancer. The process of DNA repair involves a complex interplay between several gene pathways and proteins. One such pathway is the "Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway," whose genes participate in DNA repair. FANCM, a component of this pathway, is tasked with the elimination of harmful DNA "inter-strand cross-links," and interacts with another component called MHF in order to function. The importance of the FANCM-MHF complex is well-documented: its loss can result in chromosomal instabilities that can lead to diseases such as FA itself and cancer. However, little is known about its structure and the basis of its stability.

Against this backdrop, Associate Professor Tatsuya Nishino and his colleague Dr. Sho Ito from Tokyo University of Science decided to explore the crystalline structure of this intriguing complex using X-ray diffraction techniques. "DNA damage and chromosome segregation are mechanisms necessary for the maintenance and inheritance of genes possessed by all organisms. MHF (also known as CENP-SX) is an enigmatic complex that plays a role in DNA repair and chromosome segregation. We wanted to find out how it performs these two different functions in the hope that it might give us insights into novel phenomena," explains Prof. Nishino. Their findings are published in Acta Crystallographica Section F: Structural Biology Communications.

The scientists prepared a recombinant version of the FANCM-MHF complex, consisting of FANCM from chickens and MHF1 and MHF2. They were able to purify three different types of protein crystals--tetrahedral, needle-shaped, and rod-shaped--from similar crystallization conditions. Surprisingly, upon determining the structure with X-ray crystallography, they found that two of the crystal forms (tetrahedral and needle-shaped) contained only the MHF complex without FANCM.

Intrigued by this discovery, the scientists used biochemical techniques to examine what caused the FANCM-MHF complex to disassemble. They attributed it to the presence of a compound called 2-methyl-2, 4-pentanediol (MPD), an organic solvent commonly used in crystallography, and exposure to an oxidizing environment.

But, how exactly does the dissociation happen? The scientists believe that this may have been caused partly by certain non-conserved amino acids in the chicken FANCM which causes the complex to aggregate with other FANCM-MHF complexes and disassemble. Additionally, they surmise that the small, flexible structure of MPD may have also allowed it to bind to and facilitate the release of FANCM, dismantling the complex.

The findings are extraordinary and can be used to improve the stability of the FANCM-MHF complex for future studies on its structure and function. Dr. Ito believes we have much to expect in the future from this complex. "A good understanding of this complex can help us treat cancer and genetic diseases, create artificial chromosomes, and even develop new biotechnological tools," he speculates.

Thanks to Prof. Nishino and Dr. Ito's efforts, we are already one step closer to that goal!

INFORMATION:

About The Tokyo University of Science

Tokyo University of Science (TUS) is a well-known and respected university, and the largest science-specialized private research university in Japan, with four campuses in central Tokyo and its suburbs and in Hokkaido. Established in 1881, the university has continually contributed to Japan's development in science through inculcating the love for science in researchers, technicians, and educators.

With a mission of "Creating science and technology for the harmonious development of nature, human beings, and society", TUS has undertaken a wide range of research from basic to applied science. TUS has embraced a multidisciplinary approach to research and undertaken intensive study in some of today's most vital fields. TUS is a meritocracy where the best in science is recognized and nurtured. It is the only private university in Japan that has produced a Nobel Prize winner and the only private university in Asia to produce Nobel Prize winners within the natural sciences field.

Website: https://www.tus.ac.jp/en/mediarelations/

About Professor Tatsuya Nishino from Tokyo University of Science

Tatsuya Nishino is an associate professor at the Department of Biological Science and Technology at Tokyo University of Science, Japan. He received his masters and Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree from Osaka University, Japan in 1997 and 2001, respectively. His research area is molecular biology, where he works on structural biology of complexes involved in chromosome partitioning and chromosome segregation. He has 30 publications to his credit with over 1900 citations. Details about his research can be found here: https://nishinotatsuya.wixsite.com/toppage

Funding information

This work was supported by the collaboration project of the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research; BINDS) from AMED (Grant No. 1739), NIG-JOINT (Grant Nos. 6A2017, 2A2018 and 85A2019), Cooperative Research Program of the Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University (Grant Nos. CR-17-05, CR-18-05 and CR-19-05), and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Nos. 16K07279 and 20K06512).

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-17

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections are among the major global health problems. Particularly problematic is the high number of chronic courses of the disease, causing the deaths of more than 800.000 people globally every year. So far, there is no therapy to cure the condition. "With the discovery of a new hepatitis B virus in donkeys and zebras capable of causing prolonged infections, we now have the opportunity for a better understanding of the chronic course of the disease and thus also for mitigation or prevention of severe clinical consequences," explains Prof. Dr. Jan Felix Drexler, DZIF ...

2021-03-17

A new study uncovers which cell types can be infected by SARS-CoV-2 due to their viral entry factors. The study also suggests that increased gene expression of these viral entry factors in some individuals partially explains the differences of COVID-19 severity reported in relation to age, gender and smoking status. The study evolved from the Human Cell Atlas Lung Biological Network with main contributions from Helmholtz Zentrum München, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, the Wellcome Sanger Institute and University Medical Center Groningen.

COVID-19 does not affect everyone in the same way. While the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 primarily ...

2021-03-17

The health of women aged 65 and over appears to be related, in addition to their own socioeconomic characteristics, with that of their partners, as a result of traditional gender norms. This is one of the main conclusions of research led by Jordi Gumà, a researcher at the UPF Department of Political and Social Sciences, conducted in conjunction with Jeroen Spijker, a Ramon y Cajal I3 researcher at the Centre for Demographic Studies of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (CED-UAB), focusing on the case of Spain.

The study, published in Gaceta Sanitaria, analyses the health differences among the Spanish ...

2021-03-17

An international team of scientists from the University of Turku, Finland and PennState University, USA have solved a long-standing mystery of how living organisms distinguish RNA and DNA building blocks during gene expression paving the way for the design of new antiviral drugs. The new insights were published in the journal Nature Communications.

All cellular organisms use two types of nucleic acids, RNA and DNA to store, propagate and utilize their genetic information. The synthesis of DNA is carried out by enzymes called DNA polymerases and is needed to accurately transfer the genetic information from generation to generation. ...

2021-03-17

Our immune system is very successful when it comes to warding off viruses and bacteria. It also recognizes cancer cells as potential enemies and fights them. However, cancer cells have developed strategies to evade surveillance by the immune system and to prevent immune response.

In recent years, fighting cancer with the help of the immune system has entered into clinical practice and gained increasing importance as a therapeutical approach. Current therapies apply so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors. Immune checkpoints are located on the surface ...

2021-03-17

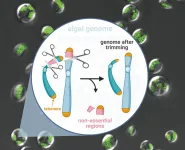

A single-celled alga undergoes genome surgery to remove non-essential parts. This can lead to a most efficient cellular factory for producing sustainable biofuels from sunlight and carbon dioxide.

Researchers from the Qingdao Institute of BioEnergy and Bioprocess Technology (QIBEBT) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have stripped hundred-kilobase genome from a type of oil-producing microalgae, knocking out genes non-essential for it to function. By doing so, they have created a "genome scalpel" that can trim microalgal genomes rapidly and creatively.

The 'minimal genome' microalgae produced is potentially useful as a model organism for further study of the molecular and biological function of every gene, or as a 'chassis' strain for synthetic biologists to augment for customized ...

2021-03-17

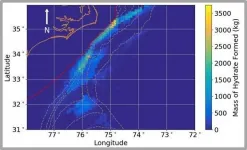

RALEIGH, N.C. -- Methane hydrate, an ice-like material made of compressed natural gas, burns when lit and can be found in some regions of the seafloor and in Arctic permafrost.

Thought to be the world's largest source of natural gas, methane hydrate is a potential fuel source, and if it "melts" and methane gas is released into the atmosphere, it is a potent greenhouse gas. For these reasons, knowing where methane hydrate might be located, and how much is likely there, is important.

A team of researchers from Sandia National Laboratories and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory have developed a new system to model the likelihood of finding methane ...

2021-03-17

Cutting-edge 3D scanners have been put to the test by researchers from the University of Southampton and partners Exceed Worldwide to help increase the quality and quantity of prosthetics services around the world.

The study, carried out within the END ...

2021-03-17

A team of scientists led by Dietmar Krautwurst from the Leibniz Institute for Food Systems Biology at the Technical University of Munich has now identified address codes in odorant receptor proteins for the first time. Similar to zip codes, the codes ensure that the sensor proteins are targeted from inside the cell to the cell surface, where they begin their work as odorant detectors. The new findings could contribute to the development of novel test systems with which the odorant profiles of foods can be analyzed in a high-throughput process and thus could be better controlled.

The ...

2021-03-17

Alchemy, which attempted to turn cheap metals such as lead and copper into gold, has not yet succeeded. However, with the development of alloys in which two or three auxiliary elements are mixed with the best elements of the times, modern alchemy can produce high-tech metal materials with high strength, such as high entropy alloys. Now, together with artificial intelligence, the era of predicting the crystal structure of high-tech materials has arrived without requiring repetitive experiments.

A joint research team of Professor Ji Hoon Shim and Dr. Taewon Jin (first author, currently at KAIST) of POSTECH's Department of Chemistry, and Professor Jaesik Park of POSTECH Graduate School of Artificial Intelligence have together developed a system that predicts ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Elusive protein complex could hold the key to treating chromosomal disorders

Scientists report on the structural and molecular factors governing the stability of a protein complex involved in DNA repair pathways in cells