(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA--A team led by scientists at Scripps Research has made a discovery suggesting that experimental antibody therapies for Parkinson's and Alzheimer's have an unintended adverse effect--brain inflammation--that may have to be countered if these treatments are to work as intended.

Experimental antibody treatments for Parkinson's target abnormal clumps of the protein alpha-synuclein, while experimental antibody treatments for Alzheimer's target abnormal clumps of amyloid beta protein. Despite promising results in mice, these potential treatments so far have not seen much success in clinical trials.

"Our findings provide a possible explanation for why antibody treatments have not yet succeeded against neurodegenerative diseases," says study co-senior author Stuart Lipton, MD, PhD, Step Family Foundation Endowed Chair in the Department of Molecular Medicine and founding co-director of the Neurodegeneration New Medicines Center at Scripps Research.

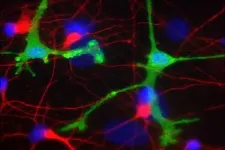

Lipton, also a clinical neurologist, says the study marks the first time that researchers have examined antibody-induced brain inflammation in a human context. Prior research was conducted in mouse brains, whereas the current study used human brain cells.

The study will appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America during the week of March 29.

An approach that may need tweaking

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's afflict more than 6 million Americans. These diseases generally feature the spread of abnormal protein clusters in the brain, with different mixes of proteins predominating in different disorders.

An obvious treatment strategy, which pharmaceutical companies began to pursue in the 1990s, is to inject patients with antibodies that specifically target and clear these protein clusters, also called aggregates.

The aggregates have included not only the large clusters that pathologists observe in patients' brains at autopsy, but also the much smaller and harder-to-detect clusters called oligomers that are now widely considered the most harmful to the brain.

Exactly how these protein clusters damage brain cells is an area of active investigation, but inflammation is a likely contributing factor. In Alzheimer's, for example, amyloid beta oligomers are known to shift brain immune cells called microglia to an inflammatory state in which they can damage or kill healthy neurons nearby.

Surprise finding

Lipton and colleagues were studying alpha synuclein oligomers' ability to trigger this inflammatory state when they encountered a surprise finding: While the oligomers on their own triggered inflammation in microglia derived from human stem cells, adding therapeutic antibodies made this inflammation worse, not better. The team traced this effect not to the antibodies per se but to the complexes formed with antibodies and their alpha synuclein targets.

Amyloid beta aggregates often co-exist with the alpha synuclein aggregates seen in Parkinson's brains, just as alpha synuclein often co-exists with amyloid beta in Alzheimer's brains.

In the study, the researchers added amyloid beta oligomers to their mix, mimicking what would happen in a clinical case, and found that it worsened inflammation. Adding anti-amyloid beta antibodies worsened it even further. They found that both alpha synuclein antibodies and amyloid beta antibodies made inflammation worse when they successfully hit their oligomer targets.

Lipton notes that virtually all prior studies of the effects of experimental antibody treatments were done with mouse microglia, whereas the key experiments in this study were done with human-derived microglia--either in cell cultures or transplanted into the brains of mice whose immune system had been engineered to accommodate the human microglia.

"We see this inflammation in human microglia, but not in mouse microglia, and thus this massive inflammatory effect may have been overlooked in the past," Lipton says.

Microglial inflammation of the kind observed in the study, he adds, could conceivably reverse any benefit of antibody treatment in a patient without being clinically obvious.

Lipton says that he and his colleagues have recently developed an experimental drug that may be able to counter this inflammation and thereby restore any benefit of antibody treatment in the human brain. They are actively working on this now.

INFORMATION:

The lead author of the study was Dorit Truder, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Lipton laboratory. Other senior authors were Rajesh Ambasudhan, PhD, an adjunct assistant professor at Scripps Research; Michael Karin, PhD, a professor at the UC San Diego School of Medicine; and Nicholas Schork, PhD, a professor at the Translational Genomics Institute in Phoenix and adjunct professor at UC San Diego and Scripps Research.

"Soluble α-synuclein/antibody complexes activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in hiPSC-derived microglia" was co-authored by Dorit Trudler, Kristopher Nazor, Yvonne Eisele, Titas Grabauskas, Nima Dolatabadi, James Parker, Abdullah Sultan, Zhenyu Zhong, Marshal Goodwin, Yona Levites, Todd Golde, Jeffery Kelly, Michael Sierks, Nicholas Schork, Michael Karin, Rajesh Ambasudhan and Stuart Lipton.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS086890, RF1 AG057409, R01 AG056259, R01 DA048882, DP1 DA041722, R01 AI043477).

KANSAS CITY, MO--Since the beginning of the pandemic, a loss of smell has emerged as one of the telltale signs of COVID-19. Though most people regain their sense of smell within a matter of weeks, others can find that familiar odors become distorted. Coffee smells like gasoline; roses smell like cigarettes; fresh bread smells like rancid meat.

This odd phenomenon is not just disconcerting. It also represents the disruption of the ancient olfactory circuitry that has helped to ensure the survival of our species and others by signaling when a reward (caffeine!) or a punishment (food poisoning!) is imminent.

Scientists ...

Dwindling water supplies and a growing population will halve per capita water use in Jordan by the end of this century. Without intervention, few households in the arid nation will have access to even 40 liters (10.5 gallons) of piped water per person per day.

Low-income neighborhoods will be the hardest hit, with 91 percent of households receiving less than 40 liters daily for 11 consecutive months per year by 2100.

Those are among the sobering predictions of a peer-reviewed paper by an international team of 17 researchers published March 29 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Jordan's deepening water crisis offers a glimpse of challenges ...

Materials such as gallium arsenide are extremely important for the production of electronic devices. As supplies of it are limited, or they can present health and environmental hazards, specialists are looking for alternative materials. So-called conjugated polymers are candidates. These organic macromolecules have semi-conductor properties, i.e. they can conduct electricity under certain conditions. One possible way of producing them in the desired two-dimensional - i.e. extremely flat - form is presented by surface chemistry, a field of research established in 2007.

Since then, many reactions have been developed and interesting materials produced for possible applications. ...

When humans look out at a visual landscape like a sunset or a beautiful overlook, we experience something -- we have a conscious awareness of what that scene looks like. This awareness of the visual world around us is central to our everyday existence, but are humans the only species that experiences the world consciously? Or do other non-human animals have the same sort of conscious experience we do?

Scientists and philosophers have asked versions of this question for millennia, yet finding answers -- or even appropriate ways to ask the question -- has proved elusive. But a team of Yale researchers recently devised an ingenious way to try to solve ...

One specific protein may be a master regulator for changing how cancer cells consume nutrients from their environments, preventing cell death and increasing the likelihood the cancer could spread, a study from the University of Notre Dame has shown.

The study, published in Cell Reports, was completed in the laboratory of Zachary Schafer, the Coleman Foundation Associate Professor of Cancer Biology in the Department of Biological Sciences.

Schafer and collaborators found a protein called SGK1, known to be activated in a variety of cancer cell types, signals the ...

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., March 29, 2021--A first-of-its-kind instrument that samples smoke from megafires and scans humidity will help researchers better understand the scale and long-term impact of fires--specifically how far and high the smoke will travel; when and where it will rain; and whether the wet smoke will warm the climate by absorbing sunlight.

"Smoke containing soot and other toxic particles from megafires can travel thousands of kilometers at high altitudes where winds are fast and air is dry," said Manvendra Dubey, a Los Alamos National Laboratory atmospheric scientist and co-author on a paper published last week in Aerosol Science and Technology. "These smoke-filled clouds can absorb ...

Among patients who return to work after a heart attack, those who work more than 55 hours per week, compared to those working an average full-time job of 35-40 hours a week, increase their odds of having a second heart attack by about twofold, according to a prospective cohort study published today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Data from the International Labour Office estimates 1 in 5 workers worldwide work over 48 hours per week. Previous studies have found an association between working long hours and increased risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. This is the first study of its kind to examine the effect of long working hours and the risk of a second cardiovascular event ...

Firearm injuries are a leading and preventable cause of injury and death among youth - responsible for an estimated 5,000 deaths and 22,000 non-fatal injury hospital visits each year in American kids. And while hospital systems are poised to tackle this issue using a public health approach, prevention efforts and policies may be differentially effective. A new study led by researchers at Children's National Hospital, finds that sociodemographic factors related to intent of injury by firearm may be useful in guiding policy and informing tailored interventions for the prevention of firearm injuries in at-risk youth.

"We sought to explore differences by injury intent in a ...

DALLAS - March. 29, 2021 - With NASA preparing to send humans to Mars in the 2030s, researchers are studying the physical effects of spending long periods in space. Now a new study by scientists at UT Southwestern shows that the heart of an astronaut who spent nearly a year aboard the International Space Station shrank, even with regular exercise, although it continued to function well.

The results were comparable with what the researchers found in a long-distance swimmer who spent nearly half a year trying to cross the Pacific Ocean.

The study, published today in Circulation, reports that astronaut Scott Kelly, now retired, lost an average of 0.74 grams - about three-tenths of an ounce - per week in the mass ...

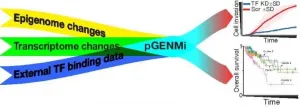

Although the development of secondary cancerous growths, called metastasis, is the primary cause of death in most cancers, the cellular changes that drive it are poorly understood. In a new study, published in Genome Biology, researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have developed a new modeling approach to better understand how tumors become aggressive.

"Researchers have identified several cellular pathways that change when a tumor becomes aggressive. However, it is difficult to understand how they affect the tumor," said Steven Offer, an assistant professor of molecular pharmacology and experimental therapeutics at Mayo Clinic, Minnesota. "We wanted to develop a simple system that can model how cancer cells form ...