(Press-News.org) EUGENE, Ore. -- April 8, 2021 -- Researchers exploring the developing central nervous system of fruit flies have identified nonelectrical cells that transition the brain from highly plastic into a less moldable, mature state.

The cells, known as astrocytes for their star-like shapes, and associated genes eventually could become therapeutic targets, said University of Oregon postdoctoral researcher Sarah Ackerman, who led the research.

"All of the cell types and signaling pathways I looked at are present in humans," Ackerman said. "Two of the genes that I identified are susceptibility genes linked to neurodevelopmental disorders including autism and schizophrenia."

The failure to close so-called critical periods of brain plasticity in development, when learning occurs rapidly and helps mold the brain, she added, also is associated with epilepsy.

The discovery is detailed in a paper published online April 7 in the journal Nature. The research was done in the Institute of Neuroscience lab of co-author Chris Doe, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and professor in the UO Department of Biology.

Astrocytes are glial cells found in large numbers in the central nervous system. They play diverse roles depending on what regions in the brain and spinal cord where they are active. They are, Ackerman said, "the guardians of synapses in terms of assuring proper functioning in both their formation and later performance."

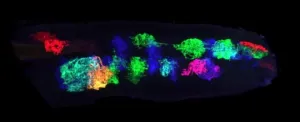

In the research, Ackerman focused on the motor circuitry of Drosophila melanogaster larvae over specific points in development. These invertebrate fruit flies are standard research models that are easily open to rapid genetic exploration of molecular mechanisms.

Ackerman used optogenetics, a light-based technology, to selectively turn motor neurons off and on. She found that these neurons exhibit striking changes to their shape and connections -- the plasticity -- in response to the manipulations.

Curiously, Ackerman and colleagues saw astrocytes pouring into the nervous system, extending fine projections and enveloping neuronal connections at the right time to switch the circuitry from plastic to stable states.

Ackerman then screened for candidate genes associated with astrocytes to determine which molecular pathways direct the window to close and shut down motor plasticity.

That work pointed directly at neuroligin, a protein on astrocyte projections, that binds to neurexin, a receptor protein on dendrites from developing neurons. Eliminating that genetic pathway extended plasticity, while precocious expression of these proteins closed plasticity too early in development.

Such changes in the timing of plasticity were also found to later impact behavior. Extending plasticity resulted in abnormal crawling of the larvae. Extending critical periods of plasticity in human development, Ackerman said, has been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders.

A tragic human example of how this critical period is vital, Doe said, may be the case of abandoned Romanian children found in an orphanage in the 1980s. Hundreds of babies had been neglected except when they were fed or washed, according to news reports.

The neglect would have occurred during that key period of plasticity when experiences and learning mold the brain, Doe said. When later removed from the orphanage four of every five of the children were unable to engage socially, according to research that followed the children into adulthood.

"My work was designed to understand what causes the shift from having a really malleable and flexible child brain to one that is more fixed and stable," Ackerman said. "Rather than focusing on the neurons, I found that these really cool star-shaped cells called astrocytes are coming into the nervous system and telling the neurons to shift from being really malleable into a stable state."

The implications of Ackerman's research are potentially profound, Doe said.

"If we can understand that mechanism of the closing of this critical developmental period, we could possibly reopen plasticity in older people who want to, say, learn a new language or learn a new task," Doe said.

That therapeutic potential is a long way off, the UO researchers said, but it is a major future goal. Ackerman's research will next move into similar studies in vertebrates, specifically using zebrafish, which were developed into a model organism for medical research at the UO in the 1970s.

Any move into therapeutics, Ackerman cautioned, will require precise titration of any drugs that may be developed so that they find "the sweet spot for plasticity."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors with Ackerman and Doe were former UO undergraduate student Nelson A. Perez-Catalan, now in a postbaccalaureate program at the University of Chicago, and Marc R. Freeman, director and senior scientist of the Vollum Institute at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute and National Institutes of Health funded the research. Ackerman was supported by a Milton Safenowitz Postdoctoral Fellowship awarded in 2017 by the ALS Association for research related to which amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's Disease.

Related Links:

Paper: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03441-2

About Chris Doe: https://ion.uoregon.edu/content/chris-doe-0

Doe Lab: https://www.doelab.org/

Nature News and Views overview: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00680-1

More than a third of the Antarctic's ice shelf area could be at risk of collapsing into the sea if global temperatures reach 4°C above pre-industrial levels, new research has shown.

The University of Reading led the most detailed ever study forecasting how vulnerable the vast floating platforms of ice surrounding Antarctica will become to dramatic collapse events caused by melting and runoff, as climate change forces temperatures to rise.

It found that 34% of the area of all Antarctic ice shelves - around half a million square kilometres - including 67% of ice shelf area on the Antarctic Peninsula, would be at risk of destabilisation under 4°C of warming. Limiting temperature ...

INDIANAPOLIS--Worldwide, 1 in 4 people will suffer from a depressive episode in their lifetime.

While current diagnosis and treatment approaches are largely trial and error, a breakthrough study by Indiana University School of Medicine researchers sheds new light on the biological basis of mood disorders, and offers a promising blood test aimed at a precision medicine approach to treatment.

Led by Alexander B. Niculescu, MD, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry at IU School of Medicine, the study was published today in the high impact journal Molecular Psychiatry . The work builds on previous research conducted by Niculescu and his colleagues into blood biomarkers that track suicidality as well as pain, post-traumatic stress ...

The almost 15-million-year-old Nördlinger Ries is an asteroid impact crater filled with lake sediments. Its structure is comparable to the craters currently being explored on Mars. In addition to various other deposits on the rim of the basin, the crater fill is mainly formed by stratified clay deposits. Unexpectedly, a research team led by the University of Göttingen has now discovered a volcanic ash layer in the asteroid crater. In addition, the team was able to show that the ground under the crater is sinking in the long term, which provides important ...

LOUISVILLE, Ky. - When a new drug is being developed, the first question is, "Does it work?" The second question is, "Does it do harm?" No matter how effective a therapy is, if it harms the patient in the process, it has little value.

Doctoral student Robert Skolik and Associate Professor Michael Menze, Ph.D., in the Department of Biology at the University of Louisville, have found a way to make cell cultures respond more closely to normal cells, allowing drugs to be screened for toxicity earlier in the research timeline.

The vast majority of cells used for biomedical research are derived from cancer tissues stored in biorepositories. They are cheap to maintain, easy to grow and multiply quickly. Specifically, ...

PISCATAWAY, NJ - Adolescents who frequently see billboard or storefront advertisements for recreational cannabis are more likely to use the drug weekly and to have symptoms of a cannabis use disorder, according to a new study in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.

Despite use being illegal for those below age 21 even in states that have approved recreational marijuana, "legalization may alter the ways that youth use cannabis," write the study authors, led by Pamela J. Trangenstein, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

An increasing number of states have legalized or are considering legalizing recreational marijuana, and public concern over the risks of cannabis use has declined in recent ...

A horse's gut microbiome communicates with its host by sending chemical signals to its cells, which has the effect of helping the horse to extend its energy output, finds a new study published in Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. This exciting discovery paves the way for dietary supplements that could enhance equine athletic performance.

"We are one of the first to demonstrate that certain types of equine gut bacteria produce chemical signals that communicate with the mitochondria in the horse's cells that regulate and generate energy," says Eric Barrey, author of this study and the Integrative Biology and Equine Genetics team leader at the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment, France. "We believe that metabolites - small molecules created ...

Eliminating racist and anti-LGBTQ policies is essential to improving the health of Black gay, bisexual and other sexual minority men, according to a Rutgers-led research team.

The study, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, examined the impact that U.S. state-level structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies have on the psychological and behavioral health of Black and white sexual minority men.

"Our results illuminate the compounding effects of racist and anti-LGBTQ policies and their implementation for Black gay, bisexual, and queer men. To improve mental and physical health and support their human rights, these oppressive policies must be changed," said lead author Devin English, an assistant professor at Rutgers School of Public Health.

The researchers ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - An invention from Purdue University innovators may provide a new option to use directed energy for biomedical and defense applications.

The Purdue invention uses composite based nonlinear transmission lines (NLTLs) for a complete high-power microwave system, eliminating the need for multiple auxiliary systems. The interest in NLTLs has increased in the past few decades because they offer an effective solid-state alternative to conventional vacuum-based, high-power microwave generators that require large and expensive external systems, such as cryogenic electromagnets and high-voltage nanosecond pulse generators.

NLTLs have proven ...

Doublespeak, or the use of euphemisms to sway opinion, lets leaders avoid the reputational costs of lying while still bringing people around to their way of thinking, a new study has found.

Researchers at the University of Waterloo found that the use of agreeable euphemistic terms biases people's evaluations of actions to be more favourable. For example, replacing a disagreeable term, "torture," with something more innocuous and semantically agreeable, like "enhanced interrogation."

"Like the much-studied phenomenon of 'fake news,' manipulative language can serve as a tool for misleading the public, doing so not with falsehoods but rather with the strategic use of euphemistic language," said Alexander Walker, lead author of the study and a PhD candidate in cognitive ...

Single-cell transcriptomic methods allow scientists to study thousands of individual cells from living organisms, one-by-one, and sequence each cell's genetic material. Genes are activated differently in each cell type, giving rise to cell types such as neurons, skin cells and muscle cells.

Single-cell transcriptomics allows scientists to identify the genes that are active in each individual cell type, and discover how these genetic differences change cellular identity and function. Careful study of this data can allow new cell types to be discovered, ...