Researchers engineer probiotic yeast to produce beta-carotene

2021-04-12

(Press-News.org) Researchers have genetically engineered a probiotic yeast to produce beta-carotene in the guts of laboratory mice. The advance demonstrates the utility of work the researchers have done to detail how a suite of genetic engineering tools can be used to modify the yeast.

"There are clear advantages to being able to engineer probiotics so that they produce the desired molecules right where they are needed," says Nathan Crook, corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at North Carolina State University. "You're not just delivering drugs or nutrients; you are effectively manufacturing the drugs or nutrients on site."

The study focused on a probiotic yeast called Saccharomyces boulardii. It is considered probiotic because it can survive and thrive in the gut, whereas most other yeast species either can't tolerate the heat or are broken down by stomach acid. It also can inhibit certain gut infections.

Previous research had shown that it was possible to modify S. boulardii to produce a specific protein in the mouse gut. And there are many well-established tools for genetically engineering baker's yeast, S. cerevisiae - which is used in a wide variety of biomanufacturing applications. Crook and his collaborators wanted to get a better understanding of which genetic engineering tools would work in S. boulardii.

Specifically, the researchers looked at two tools that are widely used for gene editing with the CRISPR system and dozens of tools that were developed specifically for modifying S. cerevisiae.

"We were a little surprised to learn that most of the S. cerevisiae tools worked really well in S. boulardii," Crook says. "Honestly, we were relieved because, while they are genetically similar, the differences between the two species are what make S. boulardii so interesting, from a therapeutic perspective."

Once they had established the viability of the toolkit, researchers chose to demonstrate its functionality modifying S. boulardii to produce beta-carotene. Their rationale was both prosaic and ambitious.

"On the one hand, beta-carotene is orange - so we could tell how well we were doing just by looking at the colonies of yeast on a petri dish: they literally changed color," Crook says. "On a more ambitious level, we knew that beta-carotene is a major provitamin A carotenoid, which means that it can be converted into vitamin A by the body - and we knew that vitamin A deficiency is a major public health problem in many parts of the world. So why not try to develop something that has the potential to be useful?"

Researchers tested the modified S. boulardii in a mouse model and found that the yeast cells successfully created beta-carotene in the guts of mice.

"This is a proof of concept, so there are a lot of outstanding questions," Crook says. "How much of this beta-carotene is getting absorbed by the mice? Are these biologically relevant amounts of beta-carotene? Would it work in humans? All of those are questions we'll have to address in future work. But we're excited to see what happens. And we're excited that these tools are now publicly available for use by others in the research community."

INFORMATION:

The paper, "In situ biomanufacturing of small molecules in the mammalian gut by probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii," appears in the journal ACS Synthetic Biology. Co-first authors of the paper are Deniz Durmusoglu and Ibrahim Al'Abri - both Ph.D. students at NC State. The paper was co-authored by Scott Collins, a Ph.D. student at NC State; Junrui Cheng, a postdoctoral researcher at NC State; Abdulkerim Eroglu, an assistant professor of nutrigenomics in the Department of Molecular and Structural Biochemistry and Plants for Human Health Institute at NC State University; and Chase Beisel, a professor at the Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research.

The work was done with support from the National Science Foundation, under grant CBET-1934284; and the Novo Nordisk Foundation, under grant NNF19SA0035474.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-12

Spanking may affect a child's brain development in similar ways to more severe forms of violence, according to a new study led by Harvard researchers.

The research, published recently in the journal Child Development, builds on existing studies that show heightened activity in certain regions of the brains of children who experience abuse in response to threat cues.

The group found that children who had been spanked had a greater neural response in multiple regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), including in regions that are part of the salience network. These areas of the brain respond to cues in the environment that tend ...

2021-04-12

Energy flows through a system of atoms or molecules by a series of processes such as transfers, emissions, or decay. You can visualize some of these details like passing a ball (the energy) to someone else (another particle), except the pass happens quicker than the blink of an eye, so fast that the details about the exchange are not well understood. Imagine the same exchange happening in a busy room, with others bumping into you and generally complicating and slowing the pass. Then, imagine how much faster the exchange would be if everyone stepped back and created a safe bubble for the pass to happen unhindered.

An international collaboration of scientists, including UConn Professor of Physics Nora Berrah and post-doctoral researcher ...

2021-04-12

New York, NY - Major depressive disorder is highly prevalent, with one in five people experiencing an episode at some point in their life, and is almost twice as common in women than in men. Antidepressants are usually given as a first-line treatment, including during pregnancy, either to prevent the recurrence of depression, or as acute treatment in newly depressed patients. Antidepressant use during pregnancy is widespread and since antidepressants cross the placenta and the blood-brain barrier, concern exists about potential long-term effects of intrauterine antidepressant exposure in the unborn child.

Using the Danish National Registers to follow more than 42,000 singleton babies born ...

2021-04-12

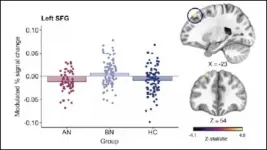

Stress alters brain activity in self-inhibition areas yet doesn't trigger binge-eating, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

People who binge-eat, a hallmark symptom of several eating disorders, can feel out of control and unable to stop, and often binge after stressful events. This led scientists to theorize stress impairs the brain regions responsible for inhibitory control -- the ability to stop what you are about to do or currently doing -- and triggers binge-eating.

Westwater et al. tested this theory by using fMRI to measure the brain activity of women with anorexia, bulimia, or without ...

2021-04-12

A unique residential study has concluded that, contrary to perceived wisdom, people with eating disorders do not lose self-control - leading to binge-eating - in response to stress. The findings of the Cambridge-led research are published today in the Journal of Neuroscience.

People who experience bulimia nervosa and a subset of those affected by anorexia nervosa share certain key symptoms, namely recurrent binge-eating and compensatory behaviours, such as vomiting. The two disorders are largely differentiated by body mass index (BMI): adults affected by anorexia nervosa tend to have BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2. More than 1.6 million people in ...

2021-04-12

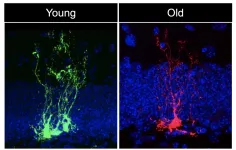

In a new study published in Cell Stem Cell, a team led by USC Stem Cell scientist Michael Bonaguidi, PhD, demonstrates that neural stem cells - the stem cells of the nervous system - age rapidly.

"There is chronological aging, and there is biological aging, and they are not the same thing," said Bonaguidi, an Assistant Professor of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Gerontology and Biomedical Engineering at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. "We're interested in the biological aging of neural stem cells, which are particularly vulnerable to the ravages of time. This has implications for the normal cognitive decline that ...

2021-04-12

Researchers have used a technique similar to MRI to follow the movement of individual atoms in real time as they cluster together to form two-dimensional materials, which are a single atomic layer thick.

The results, reported in the journal Physical Review Letters, could be used to design new types of materials and quantum technology devices. The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, captured the movement of the atoms at speeds that are eight orders of magnitude too fast for conventional microscopes.

Two-dimensional materials, such as graphene, ...

2021-04-12

New research from McMaster University suggests the pandemic has created a paradox where mental health has become both a motivator for and a barrier to physical activity.

People want to be active to improve their mental health but find it difficult to exercise due to stress and anxiety, say the researchers who surveyed more than 1,600 subjects in an effort to understand how and why mental health, physical activity and sedentary behavior have changed throughout the course of the pandemic.

The results are outlined in the journal PLOS ONE.

"Maintaining a regular exercise program is difficult at the best of times and the conditions surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic ...

2021-04-12

A new algorithm can predict which genes cause cancer, even if their DNA sequence is not changed. A team of researchers in Berlin combined a wide variety of data, analyzed it with "Artificial Intelligence" and identified numerous cancer genes. This opens up new perspectives for targeted cancer therapy in personalized medicine and for the development of biomarkers.

In cancer, cells get out of control. They proliferate and push their way into tissues, destroying organs and thereby impairing essential vital functions. This unrestricted growth is usually induced by an accumulation of DNA changes in cancer ...

2021-04-12

In the earliest stage of life, animals undergo some of their most spectacular physical transformations. Once merely blobs of dividing cells, they begin to rearrange themselves into their more characteristic forms, be they fish, birds or humans. Understanding how cells act together to build tissues has been a fundamental problem in physics and biology.

Now, UC Santa Barbara professor Otger Campàs, who also holds the Mellichamp Chair in Systems Biology and Bioengineering, and Sangwoo Kim, a postdoctoral fellow in professor Campàs lab, have approached this question, with surprising findings.

"When you have many cells physically interacting with each other, how does the system behave collectively? What is the physical state of the ensemble?" said ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers engineer probiotic yeast to produce beta-carotene