(Press-News.org) International scientists from around the world are warning that chemical pollutants in the environment have the potential to alter animal and human behaviour.

A scientific forum of 30 experts formed a united agreement of concern about chemical pollutants and set up a roadmap to help protect the environment from behaviour altering chemicals. The conclusions of their work have been published today in a paper led by Professor Alex Ford, Professor of Biology at the University of Portsmouth, in Environmental Science and Technology. Until now the effect of chemical pollutants on wildlife has been studied and risk assessed in relation to species mortality, reproduction and growth. The effect on behaviour has been suspected but never formally tested or assessed - the scientists say this needs to change.

The world leading experts came from a variety of relevant disciplines including environmental toxicology, regulatory authorities and chemicals risk assessors. Professor Alex Ford explains: "The group were in no doubt that pollution can impact the behaviour of humans and wildlife. However, our ability to regulate chemicals for these risks, and therefore safeguard the environment, is rarely used. For example, chemicals that are deliberately designed as pharmaceutical drugs to alter behaviour, such as antidepressants and antianxiety medications, have been shown to alter the behaviours of fish and invertebrates during laboratory experiments. These medications like many prescribed drugs enter the environment through wastewaters."

History shows us there are other examples of behavioural alterations from chemicals. During the 19th century, the phrases "Mad as a hatter" and "Crazy as a painter" were coined when those in these trades were found to have changed behaviour, from the use of lead and mercury. In more recent times concerns over metal toxicity resulted in the enforcement of unleaded fuels.

The scientists are not just concerned about the obvious pollutants such pharmaceutical drugs leaking into the environment but they also warn about the potential unknowns such as chemicals in plastics, washing agents, fabrics and personal care products.

The forum have come up with a roadmap they are urging policy makers, regulatory authorities, environmental leaders to act upon.

The recommendations are:

- Improve the mechanisms of how science studies contaminated-induced behavioural changes.

- Develop new and adapt existing standard toxicity tests to include behaviour.

- Develop an integrative approach to environmental risk assessment, which includes behaviour. Not just mortality, growth and reproduction.

- Improve the reliability of behavioural tests, which need to allow for variation in behavioural reactions.

- Develop guidance and training on the evaluation of reporting of behavioural studies.

- Better integration of human and wildlife behavioural toxicology.

Professor Ford said: "We know from human toxicology and pharmaceutical drug development that regulatory authorities and industry have advanced with confidence in the use of behavioural endpoints, either in chemical risk assessment and drug development. We are yet to see this used fully when addressing the health of the environment and the impacts chemicals may have on wildlife behaviours. There is real concern around our lack of knowledge of how pollutants affect wildlife and human behaviour and our current processes for assessing this are not fit for purpose."

Dr Gerd Maack, from the German Environment Agency (UBA) and host of the forum, added: "We know that chemicals affect human and wildlife behaviours, especially hormones are affecting the mating behaviour of vertebrates. However, this knowledge is still not reflected in the regulation of chemicals in Europe, partly due to a lack of standardised methods, but also due to a non-understanding of the more complex study designs by many regulators. As one of the first of its kind, this workshop brought together behavioural scientists and regulators underpinning the importance of behavioural studies for the regulation. The results of this paper will serve a road map for a better acceptance and integration of behaviour studies in regulatory practices."

Joel Allen, from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said: "Along with my U.S. EPA colleagues, Jim Lazorchak and Stephanie Padilla, and as participants in the workshop and the preparation of this manuscript, we are excited about being part of a ground-breaking area in the potential use of behavioral responses to chemicals in chemical risk assessments as well as being co-authors on this topic in the prestigious Environmental Science and Technology Journal."

Dr Marlene Agerstrand, an expert of chemicals risk assessment from the University of Stockholm said: "The regulation of chemicals is constantly evolving, as the scientific basis improves. A workshop like this, where researchers and regulators meet, could be the starting point for a change in how behavioural studies are viewed upon in the regulatory sphere. In this paper, we have identified knowledge gaps and regulatory needs with the purpose to continue the discussion with a wider stakeholder group."

The forum took place at the German Environment Agency (UBA).

INFORMATION:

Metabolic bone disease is a common complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and involves a broad spectrum of disorders of mineral metabolism that result in both skeletal and extra-skeletal consequences.

A new special issue of Calcified Tissue International brings together a comprehensive series of state-of-the-art reviews which discuss key issues in CKD and mineral and bone disorders, known as CKD-MBD. Authored by a multidisciplinary group of leading international experts, the wide-ranging reviews aim to improve the understanding and management of CKD-MBD, and advance interdisciplinary knowledge.

Professors ...

According to a Finnish study, the structure and function of the brain areas involved in emotions and their regulation are altered in both psychopathic criminal offenders and otherwise well-functioning individuals who have personality traits associated with psychopathy.

Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterised by persistent antisocial behaviour, impaired empathy, and bold, disinhibited and egotistical traits. However, similar antisocial traits are also common, yet less pronounced, with people who are well-off psychologically and socially. It is possible that the characteristics related to psychopathy form a continuum where only the extreme characteristics ...

Bern's ice core researchers were already able to demonstrate in 2008 how the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere has changed over the past 800,000 years. Now, using the same ice core from the Antarctic, the group led by Bernese climate researcher Hubertus Fischer shows the maximum and minimum values between which the mean ocean temperature has fluctuated over the past 700,000 years. The results of the reconstruction have just been published in the journal Climate of the Past.

The study's key findings: Mean ocean temperatures have been very similar over the last seven ice ages, averaging about 3.3 °C colder than the pre-industrial reference period, as already suggested by syntheses of deep water ...

It is an open question to what extent protection against reinfection persists after overcoming a SARS-CoV-2 infection. The "Rhineland Study", a population-based study conducted by DZNE in the Bonn area, is now providing new findings in this regard. Blood samples taken last year indicate that an important component of immunity - the levels of specific neutralizing antibodies against the coronavirus - had dropped in most of the study participants with a previous infection after four to five months. In some, antibody titers even fell below the detection limit. These results, published in the scientific journal "Nature Communications", lay the groundwork for planned follow-up studies.

Between April ...

Research breakthrough in understanding how neural systems process and store information.

A team of scientists from the University of Exeter and the University of Auckland have made a breakthrough in the quest to better understand how neural systems are able to process and store information.

The researchers, including lead author Dr Kyle Wedgwood from the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, have made a significant discovery in how a single cell can store electrical patterns, similar to memories.

They compared sophisticated mathematical modelling to lab-based experiments to determine how different parameters, such as how long it takes ...

In a new study, Dr. LU Xiankai and his colleagues from the South China Botanical Garden (SCBG) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) found that tropical forests can capture carbon dioxide (CO2) into soils and thus reduce emitted CO2. But how exactly do tropical forest soils capture atmospheric CO2?

Current knowledge of forest soil carbon sequestration mainly focuses on temperate and boreal forests, where most ecosystems are nitrogen-limited, and an increase in nitrogen supply can enhance net primary productivity (NPP) and subsequent soil carbon ...

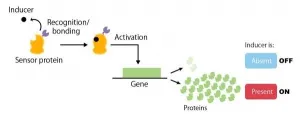

A group of researchers from Kobe University and Chiba University has successfully developed a flexible and simple method of artificially producing genetic switches for yeast, a model eukaryotic organism. The group consisted of Researcher TOMINAGA Masahiro*1, Associate Professor ISHII Jun*2 and Professor KONDO Akihiko*3 (of Kobe University's Graduate School of Science, Technology and Innovation/Engineering Biology Research Center), and Professor UMENO Daisuke et al. (of Chiba University's Graduate School of Engineering).

Genetic switches are gene regulatory networks that control gene expression. The researchers established a platform for ...

Oakland, CA-In the first study to report on the health effects of exposure to a toxic environmental chemical over three human generations, a new study has found that granddaughters whose grandmothers were exposed to the pesticide DDT have higher rates of obesity and earlier first menstrual periods. This may increase the granddaughters' risk for breast cancer as well as high blood pressure, diabetes and other cardiometabolic diseases.

The research by the Public Health Institute's Child Health and Development Studies (CHDS) and the University of California at Davis was published today ...

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - April 14, 2021 - Investigators at Wake Forest School of Medicine, part of Wake Forest Baptist Health, have identified a set of new genetic markers that could potentially lead to new personalized treatments for lung cancer.

The study appears online in Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

This study was built on a previous discovery by the precision oncology team at Wake Forest Baptist's Comprehensive Cancer Center, directed by Wei Zhang, Ph.D., professor of cancer biology at Wake Forest School of Medicine and a co-corresponding author of this study. Using DNA sequencing technologies, Zhang's team found that tumors with mutated KMT2 genes, a family of proteins, exhibit a feature ...

A new study based on daily COVID-19 data from Brazil details the fast spread of both cases and deaths in the country, with distinct patterns by state, and where inequities regarding the implementation of policies and resources exacerbated the spread in lower-income regions. Despite an extensive network of primary care availability, Brazil - which did not pursue a coordinated national pandemic response strategy - has suffered greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic. "[T]he federal response has been a dangerous combination of inaction and wrongdoing," write Marcia Castro and colleagues. Using daily data from State Health Offices, Castro ...