"We've known that aluminium alloys can become stronger by being stored at room temperature - that's not new information," says Adrian Lervik, a physicist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

The German metallurgist Alfred Wilm discovered this property way back in 1906. But why does it happen? So far the phenomenon has been poorly understood, but now Lervik and his colleagues from NTNU and SINTEF, the largest independent research institute in Scandinavia, have tackled that question.

Lervik recently completed his doctorate at NTNU's Department of Physics. His work explains an important part of this mystery. But first a little background, because Lervik has dug into some prehistory as well.

"At the end of the 1800s, Wilm worked to try to increase the strength of aluminium, a light metal that had the recently become available. He melted and cast a number of different alloys and tested out various cooling rates common in steel production in order to achieve the best possible strength," says Lervik.

One weekend when the weather was good Wilm decided to take a break from his experiments and instead take an early weekend to sail along the Havel River.

"He returned to the lab on Monday and continued to run tensile tests of an alloy consisting of aluminium, copper and magnesium that he had started the week before. He discovered that the alloy's strength had increased considerably over the weekend.

This alloy had simply stayed at room temperature during that time. Time had done the job that all sorts of other cooling methods couldn't do.

Today this phenomenon is called natural ageing.

The American metallurgist Paul Merica suggested in 1919 that the phenomenon must be due to small particles of the various elements that form a kind of precipitation in the alloy. But at that time there were no experimental methods that could prove this.

"Only towards the end of the 1930s could the method of X-ray diffraction prove that the alloying elements accumulated in small clusters on a nanoscale," says Lervik.

Pure aluminium consists of lots of crystals. A crystal can be seen as a block of grid sheets, where an atom sits in each square of the grid. Strength is measured in the sheets' resistance to sliding over each other.

In an alloy, a small per cent of the squares are occupied by other elements, making it a little harder for the sheets to slide across each other and resulting in increased strength.

As Lervik explains it, "An aggregate is like a small drop of paint in the grid block. The alloying elements accumulate and occupy a few dozen neighbouring squares that extend over several sheets. Together with the aluminium, they form a pattern. These drops have a different atomic structure than the aluminium and make dislocation sliding more difficult for the sheets in the grid block."

Aggregates of alloying elements are known as "clusters. In technical language they are called Guinier-Preston (GP) zones after the two scientists who first described them. In the 1960s, it became possible to see GP zones through an electron microscope for the first time, but it's taken until now to view them at the single-atom level.

"In recent years, numerous scientists have explored the composition of aggregates, but little work has been done to understand their nuclear structure. Instead, many studies have focused on optimizing alloys by experimenting with age hardening at different temperatures and for different lengths of time," says Lervik.

Age hardening and creating strong metal mixtures are clearly very important in an industrial context. But very few researchers and people in the industry have cared much about what the clusters actually consist of. They were simply too small to prove.

Lervik and his colleagues thought differently.

"With our modern experimental methods, we managed to take atomic-level pictures of the clusters with the transmission electron microscope in Trondheim for the first time in 2018," says Lervik.

"He and his team studied alloys of aluminium, zinc and magnesium. These are becoming increasingly important in the automotive and aerospace industries."

The research team also determined the clusters' chemical composition using the instrument for atomic probe tomography that was recently installed at NTNU. The infrastructure programme at the Research Council of Norway made this discovery possible. This investment has already contributed to new fundamental insights into metals.

The researchers studied alloys of aluminium, zinc and magnesium, known as 7xxx series Al alloys. These light metal alloys are becoming increasingly important in the automotive and aerospace industries.

"We found clusters with a radius of 1.9 nanometres buried in the aluminium. Although numerous, they are difficult to observe under a microscope. We only managed to identify the atomic structure under special experimental conditions," says Lervik.

This is part of the reason why no one has done this before. Performing the experiments is tricky and requires advanced modern experimental equipment.

"We experienced just how tricky this was several times. Even though we managed to take a picture of the clusters and could extract some information about their composition, it took several years before we understood enough to be able to describe the nuclear structure," says Lervik.

So what exactly makes this work so special? In the past, people have assumed that aggregates consist of the alloying elements, aluminium and perhaps vacancies (empty squares) that are more or less randomly arranged.

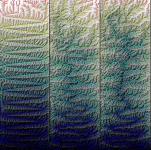

"We found that we can describe all the clusters we've observed based on a unique geometric spatial figure called a 'truncated cube octahedron,'" says Lervik.

Right here anyone without a background in physics or chemistry may want to skim the next sections or jump straight to the middle heading "Important for understanding heat treatment."

To understand the illustration above, we must first accept that an aluminium crystal (square block) can be visualized as a stack of cubes, each with atoms on the 8 corners and 6 sides.

This structure is an atomic side-centred cubic lattice. The geometric figure is like a cube, with an outer shell formed from the surrounding cubes. We describe it as three shells around the centre cube: one for the sides, one for the corners and the outermost shell. These shells consist of 6 zinc, 8 magnesium and 24 zinc atoms, respectively.

The middle of the body (cube) may contain an extra atom - an 'interstitial' - which in this illustration can be described as being located between the spaces (squares) of aluminium.

This single figure further explains all larger cluster units by their ability to connect and expand in three defined directions. The picture also explains observations previously reported by others. These cluster units are what contribute to increased strength during age hardening.

Important for understanding heat treatment

"Why is this cool? It's cool because natural ageing isn't usually the last step in processing an alloy before it's ready to be used," says Lervik.

These alloys also go through a final heat treatment at higher temperatures (130-200°C) to form larger precipitates with defined crystal structures. They bind the atomic planes (sheets) even more tightly together and strengthen it considerably .

"We believe that understanding the atomic structure of the clusters formed by natural aging is essential to further understand the process of forming the precipitates that determine so much of the material's properties. Do the precipitates form on the clusters or do the clusters transform into precipitates during heat treatment? How can this be optimized and utilized? Our further work will try to answer these questions," says Lervik.

INFORMATION:

References: A. Lervik, E. Thronsen, J. Friis, C. D. Marioara, S. Wenner, A. Bendo, K. Matsuda, R. Holmestad, S. J. Andersen. Atomic structure of solute clusters in Al - Zn - Mg alloys. Acta Materialia, Volume 205, 15 February 2021, 116574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2020.116574