(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- Tens of millions of people worldwide are affected by diseases like macular degeneration or have had accidents that permanently damage the light-sensitive photoreceptors within their retinas that enable vision.

The human body is not capable of regenerating those photoreceptors, but new advances by medical researchers and engineers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison may provide hope for those suffering from vision loss. They described their work today in the journal Science Advances.

Researchers at UW-Madison have made new photoreceptors from human pluripotent stem cells. However, it remains challenging to precisely deliver those photoreceptors within the diseased or damaged eye so that they can form appropriate connections, says David Gamm, director of the McPherson Eye Research Institute and professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health.

"While it was a breakthrough to be able to make the spare parts -- these photoreceptors -- it's still necessary to get them to the right spot so they can effectively reconstruct the retina," he says. "So, we started thinking, 'How can we deliver these cells in a more intelligent way?' That's when we reached out to our world-class engineers at UW-Madison."

Gamm is collaborating with colleagues Shaoqin (Sarah) Gong, a professor of biomedical engineering, Wisconsin Institute for Discovery faculty member and an expert in biomaterials, and Zhenqiang (Jack) Ma, a professor of electrical and computer engineering and an expert in semiconductors whose lab is experienced in sophisticated micro- and nanofabrication. Together, their research groups have developed a micro-molded scaffolding photoreceptor "patch" designed to be implanted under a damaged or diseased retina.

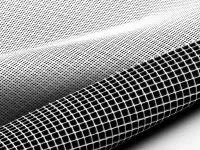

In 2018, the team developed its first biodegradable polymer scaffolding with wine-glass-shaped pores to hold the photoreceptor cells in place. However, that design wasn't optimal since it could not fit many photoreceptors in each pore.

In this second-generation scaffold, the team opted for an "ice cube tray" design, which can hold three times as many cells while reducing the amount of biomaterial used for the scaffolding to facilitate faster degradation of the synthetic material within the eye.

Gong and her team, led by graduate student Ruosen (Alex) Xie, screened a long list of potential biomaterials before deciding on poly(glycerol-sebacate), or PGS, a material that is compatible with the retina and can be safely metabolized by the body after degradation. The Gong lab optimized the formulation and further developed a curing process to achieve desirable material properties for making the scaffolds.

"We wanted the material to be very strong," says graduate student and co-first author Allison Ludwig, who works in Gamm's lab, "and in the eye, it degrades pretty quickly over about two months. That's ideal for the human retina."

The process of crafting the scaffold with the desired mechanical strength and precise dimensions was performed by co-first author Inkyu Lee and graduate student Juhwan Lee, who work in Ma's lab. To achieve highly ordered 3D ice cube tray-shaped microstructures from the biodegradable and biocompatible PGS films with micron-sized features, they developed multi-step micro-molding techniques that can transfer patterns to flexible polymer films.

The final scaffold fabrication work was tedious and frustrating. Fractures and imperfections occurred on the soft scaffolds during demounting from the micro molds, rendering the micro molds inoperable for further use -- but Inkyu Lee ultimately discovered that soaking the scaffold in isopropyl alcohol allowed it to release cleanly.

"The fabrication processes creating a scaffold with micron-sized features involve a lot of person-dependent technical handling skills, which makes the production of scaffolds with a uniform quality difficult," he says. "I wanted to achieve something that is repeatable regardless of an operator's handling skills. I was enlightened by the fact that the PGS polymer swells in isopropyl alcohol. Exploiting this property ultimately facilitated the release of the scaffolds from the micro molds."

Using this approach, Ma's lab was able to reliably demount the scaffold from micro molds without surface defects and retain the mold's microstructures, maintaining the mold surface integrity for reuse. In the end, microscopy revealed the fabrication technique was a success, reliably reproducing a perfect ice cube tray-shaped scaffold capable of holding more than 300,000 photoreceptors in approximately the area of the human macula, the center of the retina.

"Overall, the results are very exciting and significant," says Ma. "Once we figured out the recipe, mass production became immediately possible, and commercialization will be very easy. The fabrication methods can be used to create many other types of soft scaffolds for various biomedical applications, such as complicated tissue engineering, etc."

The team has disclosed the scaffold structure and the fabrication method to the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, which has filed a patent application.

The team plans to continue optimizing its scaffolding shape, fabrication technique and bio-resorbable materials for faster production to satisfy future surgical needs. In the meantime, the current iteration of the scaffolding patch is almost ready for surgical testing in large animals. If successful, the patch will eventually be tested in humans.

"We're hoping these early generation retinal patches will be safe and restore some vision. Then we'll be able to innovate and improve upon the technology and the outcomes over time," says Gamm. "We didn't start out with supercomputers on our wrists and we're not going to start out by completely erasing blindness in our first attempt. But we're very excited about taking a significant step in that direction."

INFORMATION:

Other University of Wisconsin-Madison authors include M. Joseph Phillips, Benjamin Sajdak, and Lindsey Jager.

This research was supported by the Department of Defense (grant No. W81XWH-20-1-0655), the National Institutes of Health (P51OD011106 and U54HD090256), the Foundation Fighting Blindness, the Harrington Discovery Institute, Research to Prevent Blindness, and the Carl and Mildred Reeves Foundation.

--Jason Daley, jgdaley@wisc.edu

Contact: Zhenqiang "Jack" Ma, mazq@engr.wisc.edu; Sarah Gong, shaoqingong@wisc.edu; David Gamm, dgamm@wisc.edu

DOWNLOAD IMAGES: https://uwmadison.box.com/v/eye-cell-scaffold

Water is abundant in our solar system. Even outside of our own planet, scientists have detected ice on the moon, in Saturn's rings and in comets, liquid water on Mars and under the surface of Saturn's moon Enceladus, and traces of water vapor in the scorching atmosphere of Venus. Studies have shown that water played an important role in the early evolution and formation of the solar system. To learn more about this role, planetary scientists have searched for evidence of liquid water in extraterrestrial materials such as meteorites, most of which originate from asteroids that formed in the early history of the solar system.

Scientists have even found water as hydroxyls and molecules in meteorites in the context ...

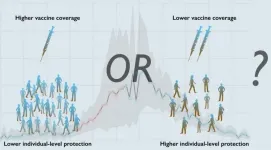

Two of the COVID-19 vaccines currently approved in the United States require two doses, administered three to four weeks apart, however, there are few data indicating how best to minimize new infections and hospitalizations with limited vaccine supply and distribution capacity. A study published on 21st April, 2021 in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Seyed Moghadas at York University in Toronto, Canada, and colleagues suggests that delaying the second dose could improve the effectiveness of vaccine programs.

The emergence of novel, more contagious SARS-CoV-2 variants has led to a public health debate on whether to vaccinate more individuals with the first ...

Swing voters in battleground states delivered Donald Trump his unexpected victory in the 2016 presidential election, suggests a new study coauthored by Yale political scientist Gregory A. Huber.

The study, published on April 21 in the journal Science Advances, compares the outcomes of the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections in six key states: Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The analysis merged voter turnout records of 37 million individuals with precinct-level election returns to determine the sources of Trump's electoral success. It examined the relative roles of conversion -- voters switching their support from one party to the ...

Boston, MA - In a worldwide survey, pregnant and postpartum women reported high levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and post-traumatic stress during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Such high levels of distress may have potential implications for women and for fetal and child health and development, according to the study.

The study will be published online in PLOS ONE on April 21, 2021.

"We expected to see an increase in the proportion of pregnant and postpartum women reporting mental health distress, as they are likely to be worried or have questions about their babies' health and development, ...

In the field of robotics, researchers are continually looking for the fastest, strongest, most efficient and lowest-cost ways to actuate, or enable, robots to make the movements needed to carry out their intended functions.

The quest for new and better actuation technologies and 'soft' robotics is often based on principles of biomimetics, in which machine components are designed to mimic the movement of human muscles--and ideally, to outperform them. Despite the performance of actuators like electric motors and hydraulic pistons, their rigid form limits how they can be deployed. As robots transition to more ...

Researchers of the University of Barcelona, together with researchers from the University of Zurich (Switzerland) and Brown University (United States), have analysed more than 10,000 evaluations that were carried out to candidates who wish to hold a public teaching permanent in Catalonia. The objective was to study how the decision by the committee of evaluators is affected by the fact that each candidate holds a certain position in the lists of people to be assessed. The study, published in the journal Science Advances, identifies a new cognitive bias that researchers have named "generosity-erosion effect". It involves that once the evaluators have scored one candidate generously, ...

Brandi Wren was studying social distancing and infections before masking tape marks appeared on the grocery store floor and plastic barriers went up in the post office.

Wren, a visiting scholar in the Department of Anthropology at Purdue University, spent a year studying wild vervet monkey troops in South Africa, tracking both their social grooming behavior and their parasite load. Her results, some of which were published Wednesday (April 21) in PLOS ONE showed evidence that monkeys carrying certain gastrointestinal parasites do not groom others as much as those without the parasite, and that routes of transmission may not be as clear cut as biologists think.

With implications for both animal behavior and human health, Wren's results open new avenues for research and ...

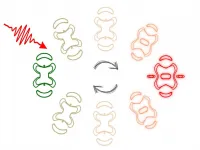

Making the speed of electronic technology as fast as possible is a central aim of contemporary materials research. The key components of fast computing technologies are transistors: switching devices that turn electrical currents on and off very quickly as basic steps of logic operations. In order to improve our knowledge about ideal transistor materials, physicists are constantly trying to determine new methods to accomplish such extremely fast switches. Researchers from the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society in Berlin and the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter in Hamburg have now figured out ...

Women who experience partner violence at a young age don't always show physical signs of abuse and don't always disclose -- or recognize -- the dangerous position they're in. A new study from Michigan State University is one of the first to examine multiple factors that influence young women's disclosure of partner violence that occurred during their first relationships, when they were just under 15 years old, on average.

"Physical abuse is widely understood as unhealthy, wrong and abusive, but sexual violence and coercive control are less understood and still pretty hidden, especially among young women," said Angie C. Kennedy, MSU associate professor of ...

East Hanover, NJ. April 21, 2021. Kessler Foundation researchers showed that people with multiple sclerosis (MS) experience subtle language impairments that standard neuropsychological tests may incorrectly attribute to impaired executive functions. The article, "The role of language ability in verbal fluency of individuals with multiple sclerosis" (doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102846) was published on February 16, 2021, in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders.

The authors are Nancy D. Chiaravalloti, PhD, director of the Centers for Neuropsychology, Neuroscience, and Traumatic Brain Injury Research at Kessler Foundation, Lauren B. Strober, PhD, senior research scientist at the Center for Neuropsychology and Neuroscience ...