(Press-News.org) Like a fence or barricade intended to stop unwanted intruders, the skin serves as a barrier protecting the body from the hundreds of allergens, irritants, pollutants and microbes people come in contact with every day. In patients with eczema, or atopic dermatitis, the most common inflammatory human skin disease, the skin barrier is leaky, allowing intruders – pollen, mold, pet dander, dust mites and others – to be sensed by the skin and subsequently wreak havoc on the immune system.

While the upper-most layer of the skin – the stratum corneum – has been pinned as the culprit in previous research, a new study published today in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology found that a second skin barrier structure, consisting of cell-to-cell connections known as tight junctions, is also faulty in eczema patients and likely plays a role in the development of the disease. Tightening both leaky barriers may be an effective treatment strategy for eczema patients, who often have limited options to temper the disease.

"Over the past five years, disruption of the skin barrier has become a central hypothesis to explain the development of eczema," said Lisa Beck, M.D., lead study author and associate professor in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Rochester Medical Center. "Our findings challenge the belief that the top layer of the skin or stratum corneum is the sole barrier structure: It suggests that both the stratum corneum and tight junctions need to be defective to jumpstart the disease."

Currently, there are no treatments that target skin barrier dysfunction in eczema. To treat eczema, which causes dry, red, itchy skin, physicians typically prescribe anti-inflammatory drugs, like prednisone, and a variety of topical anti-inflammatory creams and ointments. But, modest benefit, negative side effects and cost concerns associated with these therapies leave patients and doctors eagerly awaiting new alternatives.

"We want to figure out what current eczema therapies do to both barrier structures and start thinking about new treatments to close the breaks that let irritants in and water out and subsequently drive the inflammation and dryness that is characteristic of the disease," noted Beck, who treats eczema patients in addition to conducting research on the condition.

To better understand the role of tight junctions in eczema, Beck and her team studied skin samples from eczema patients and healthy individuals. Using resistance and permeability tests, they discovered that tight junctions, which act like a gate controlling the passage of water and particles, were strong and tight in healthy skin samples, yet loose and porous in the skin of eczema patients.

On further investigation, they found that a particular tight junction protein, claudin-1, which determines the strength and permeability of tight junctions in skin, is significantly reduced in the skin of eczema patients, but not in healthy individuals or individuals with psoriasis, another common chronic skin disease. They demonstrated that reducing claudin-1 expression in skin cells from healthy donors made the tight junctions leaky and more permeable, a finding in line with results of other research groups.

"Since claudin-1 was only reduced in eczema patients, and not the other controls, it may prove to be a new susceptibility gene in this disease," said Anna De Benedetto, M.D., postdoctoral-fellow at the Medical Center and first author of the new study. "Our hypothesis is that reduced claudin-1 may enhance the reactivity to environmental antigens and lead to greater allergen sensitization and susceptibility in people with eczema."

If the team's hypothesis stands up in future research, increasing claudin-1 to combat eczema could be a new treatment approach worth exploring. The University of Rochester has applied for patent protection for increasing claudin-1 with drug compounds to treat eczema.

Barrier problems, and in particular tight junction defects, are recognized as a common feature in many other inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease and asthma, where the lining of the intestine and the airways is weakened, which is why Beck and her team decided to focus on the role of this barrier structure in eczema.

Eczema affects up to 17 percent of children and about six percent of adults in the United States – close to 15 million Americans. While there are varying severities of eczema, all have an itch that can make it difficult to focus on daily activities and to sleep. People with eczema are often counseled to minimize their exposure to allergens, but that is a difficult task given the hundreds of allergens people are exposed to each day.

Beck, who began the research while at Johns Hopkins University, plans to build on these findings by investigating the immunologic consequences of tight junction disruption in the skin and whether there is a relationship between barrier disruption and subjects' intractable itch. In addition, as part of a contract with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health, called the Atopic Dermatitis Research Network, Beck, in collaboration with Kathleen Barnes, Ph.D., at Johns Hopkins, will perform gene mapping of claudin-1 to try to identify mutations in patients with eczema.

INFORMATION:

The current research was funded by the Atopic Dermatitis and Vaccinia Network at NIAID, the National Eczema Association and the Mary Beryl Patch Turnbull Scholar Program. Along with Beck and De Benedetto, Andrei I. Ivanov, Ph.D., Steve N. Georas, M.D., Kunzhong Zhang, Ph.D., Sadasivan Vidyasagar, M.D., Ph.D., and Takeshi Yoshida, Ph.D., from the University of Rochester Medical Center participated in the research. Scientists from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, National Jewish Health, the University of California, San Diego, Children's Hospital Boston, Oregon Health & Science University, the University of Bonn (Germany), Technische Universität München (Germany) and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health contributed as well.

Study reveals major shift in how eczema develops

Not 1, but 2 skin barriers influential in most common skin disease

2010-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ancient raindrops reveal a wave of mountains sent south by sinking Farallon plate

2010-12-18

50 million years ago, mountains began popping up in southern British Columbia. Over the next 22 million years, a wave of mountain building swept (geologically speaking) down western North America as far south as Mexico and as far east as Nebraska, according to Stanford geochemists. Their findings help put to rest the idea that the mountains mostly developed from a vast, Tibet-like plateau that rose up across most of the western U.S. roughly simultaneously and then subsequently collapsed and eroded into what we see today.

The data providing the insight into the mountains ...

Computer games and science learning

2010-12-18

Computer games and simulations are worthy of future investment and investigation as a way to improve science learning, says LEARNING SCIENCE: COMPUTER GAMES, SIMULATIONS, AND EDUCATION, a new report from the National Research Council. The study committee found promising evidence that simulations can advance conceptual understanding of science, as well as moderate evidence that they can motivate students for science learning. Research on the effectiveness of games designed for science learning is emerging, but remains inconclusive, the report says.###

The report is available ...

You only live once: our flawed understanding of risk helps drive financial market instability

2010-12-18

Our flawed understanding of how decisions in the present restrict our options in the future means that we may underestimate the risk associated with investment decisions, according to new research by Dr Ole Peters from Imperial College London. The research, published today in the journal Quantitative Finance, suggests how policy makers might reshape financial risk controls to reduce market instability and the risk of market collapse.

Investors know that there are myriad possibilities for how a financial market might develop. Before making an investment, they try to capture ...

Efficient phosphorus use by phytoplankton

2010-12-18

Rapid turnover and remodelling of lipid membranes could help phytoplankton cope with nutrient scarcity in the open ocean.

A team led by Patrick Martin of the National Oceanography Centre has shown that a species of planktonic marine alga can rapidly change the chemical composition of its cell membranes in response to changes in nutrient supply. The findings indicate that the process may be important for nutrient cycling and the population dynamics of phytoplankton in the open ocean.

Tiny free-floating algae called phytoplankton exist in vast numbers in the upper ocean. ...

Effect of college on volunteering greatest among disadvantaged college graduates

2010-12-18

Sociologists have long known that a college education improves the chances that an individual will volunteer as an adult. Less clear is whether everyone who goes to college gets the same boost in civic engagement from the experience.

In an innovative study that compared the volunteering rates of college graduates with those of non–college graduates with similar social backgrounds and high school achievement levels, UCLA sociologist Jennie Brand found something striking: A college education has a much greater impact on volunteering rates among individuals from underprivileged ...

Ion channel responsible for pain identified by UB neuroscientists

2010-12-18

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- University at Buffalo neuroscience researchers conducting basic research on ion channels have demonstrated a process that could have a profound therapeutic impact on pain.

Targeting these ion channels pharmacologically would offer effective pain relief without generating the side effects of typical painkilling drugs, according to their paper, published in a recent issue of The Journal of Neuroscience.

"Pain is the most common symptom of injuries and diseases, and pain remains the primary reason a person visits the doctor," says Arin Bhattacharjee, PhD, ...

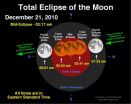

A total lunar eclipse and winter solstice coincide on Dec. 21

2010-12-18

With frigid temperatures already blanketing much of the United States, the arrival of the winter solstice on December 21 may not be an occasion many people feel like celebrating. But a dazzling total lunar eclipse to start the day might just raise a few chilled spirits.

Early in the morning on December 21 a total lunar eclipse will be visible to sky watchers across North America (for observers in western states the eclipse actually begins late in the evening of December 20), Greenland and Iceland. Viewers in Western Europe will be able to see the beginning stages of ...

NASA's LRO creating unprecedented topographic map of moon

2010-12-18

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is allowing researchers to create the most precise and complete map to date of the moon's complex, heavily cratered landscape.

"This dataset is being used to make digital elevation and terrain maps that will be a fundamental reference for future scientific and human exploration missions to the moon," said Dr. Gregory Neumann of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "After about one year taking data, we already have nearly 3 billion data points from the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter on board the LRO spacecraft, with near-uniform ...

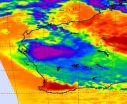

NASA satellite tracks soaking System 91S in western Australia

2010-12-18

NASA's Aqua satellite captured a series of images from its Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument over the last two days and saw the low pressure area known as System 91S make landfall in Australia. System 91S may not have become a tropical depression, but it's dropping heavy rainfall in Western Australia.

NASA's AIRS infrared instrument showed System 91S's center making landfall on Dec. 16 at 0647 UTC (1:47 a.m. EST) near the town of Carnavon in Western Australia. At that time, there was a large area of strong thunderstorms around the center of circulation, ...

New Article On OffTheGridNews.com Points to Some Challenging Questions; is Outrage Over WikiLeaks Revelations Misguided?

2010-12-18

The controversy surrounding whistle-blowing website WikiLeaks along with its creator Julian Assange continues to gain momentum as liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans have joined together in one voice to condemn the most recent leaks that Senator Diane Feinstein has described as "a serious breach of national security and could be used to severely harm the United States and its worldwide interests."

If you're looking to score popularity points in Washington now is the time to jump on the anti-Assange bandwagon and condemn the Aussie for his complicity in weakening ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Study reveals major shift in how eczema developsNot 1, but 2 skin barriers influential in most common skin disease