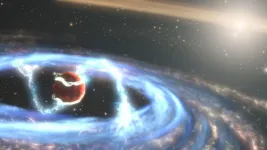

(Press-News.org) NASA's Hubble Space Telescope is giving astronomers a rare look at a Jupiter-sized, still-forming planet that is feeding off material surrounding a young star.

"We just don't know very much about how giant planets grow," said Brendan Bowler of the University of Texas at Austin. "This planetary system gives us the first opportunity to witness material falling onto a planet. Our results open up a new area for this research."

Though over 4,000 exoplanets have been cataloged so far, only about 15 have been directly imaged to date by telescopes. And the planets are so far away and small, they are simply dots in the best photos. The team's fresh technique for using Hubble to directly image this planet paves a new route for further exoplanet research, especially during a planet's formative years.

This huge exoplanet, designated PDS 70b, orbits the orange dwarf star PDS 70, which is already known to have two actively forming planets inside a huge disk of dust and gas encircling the star. The system is located 370 light-years from Earth in the constellation Centaurus.

"This system is so exciting because we can witness the formation of a planet," said Yifan Zhou, also of the University of Texas at Austin. "This is the youngest bona fide planet Hubble has ever directly imaged." At a youthful five million years, the planet is still gathering material and building up mass.

Hubble's ultraviolet light (UV) sensitivity offers a unique look at radiation from extremely hot gas falling onto the planet. "Hubble's observations allowed us to estimate how fast the planet is gaining mass," added Zhou.

The UV observations, which add to the body of research about this planet, allowed the team to directly measure the planet's mass growth rate for the first time. The remote world has already bulked up to five times the mass of Jupiter over a period of about five million years. The present measured accretion rate has dwindled to the point where, if the rate remained steady for another million years, the planet would only increase by approximately an additional 1/100th of a Jupiter-mass.

Zhou and Bowler emphasize that these observations are a single snapshot in time - more data are required to determine if the rate at which the planet is adding mass is increasing or decreasing. "Our measurements suggest that the planet is in the tail end of its formation process."

The youthful PDS 70 system is filled with a primordial gas-and-dust disk that provides fuel to feed the growth of planets throughout the entire system. The planet PDS 70b is encircled by its own gas-and-dust disk that's siphoning material from the vastly larger circumstellar disk. The researchers hypothesize that magnetic field lines extend from its circumplanetary disk down to the exoplanet's atmosphere and are funneling material onto the planet's surface.

"If this material follows columns from the disk onto the planet, it would cause local hot spots," Zhou explained. "These hot spots could be at least 10 times hotter than the temperature of the planet." These hot patches were found to glow fiercely in UV light.

These observations offer insights into how gas giant planets formed around our Sun 4.6 billion years ago. Jupiter may have bulked up on a surrounding disk of infalling material. Its major moons would have also formed from leftovers in that disk.

A challenge to the team was overcoming the glare of the parent star. PDS 70b orbits at approximately the same distance as Uranus does from the Sun, but its star is more than 3,000 times brighter than the planet at UV wavelengths. As Zhou processed the images, he very carefully removed the star's glare to leave behind only light emitted by the planet. In doing so, he improved the limit of how close a planet can be to its star in Hubble observations by a factor of five.

"Thirty-one years after launch, we're still finding new ways to use Hubble," Bowler added. "Yifan's observing strategy and post-processing technique will open new windows into studying similar systems, or even the same system, repeatedly with Hubble. With future observations, we could potentially discover when the majority of the gas and dust falls onto their planets and if it does so at a constant rate."

The researchers' results were published in April 2021 in The Astronomical Journal.

INFORMATION:

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA (European Space Agency). NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington, D.C.

Media Contacts:

Claire Andreoli

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

claire.andreoli@nasa.gov

Claire Blome

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md.

Ray Villard

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md.

Boulder, Colo., USA: Thirty-one new articles were published online ahead of

print for Geology in April. Topics include shocked zircon from the

Chicxulub impact crater; the Holocene Sonoran Desert; the architecture of

the Congo Basin; the southern Death Valley fault; missing water from the

Qiangtang Basin; sulfide inclusions in diamonds; how Himalayan collision

stems from subduction; ghost dune hollows; and the history of the Larsen C Ice Shelf. These Geology articles are online at END ...

The genome of single-celled plankton, known as dinoflagellates, is organized in an incredibly strange and unusual way, according to new research. The findings lay the groundwork for further investigation into these important marine organisms and dramatically expand our picture of what a eukaryotic genome can look like.

Researchers from KAUST, the U.S. and Germany have investigated the genomic organization of the coral-symbiont dinoflagellate Symbiodinium microadriaticum. The S. microadriaticum genome had already been sequenced and assembled into segments known as scaffolds but lacked a chromosome-level assembly.

The team used a technique known as Hi-C to detect ...

DURHAM, N.C. - Mantis shrimp don't need baby food. They start their life as ferocious predators who know how to throw a lethal punch.

A new study appearing April 29 in the Journal of Experimental Biology shows that larvae of the Philippine mantis shrimp (Gonodactylaceus falcatus) already display the ultra-fast movements for which these animals are known, even when they are smaller than a short grain of rice.

Their ultra-fast punching appendages measure less than 1 mm, and develop right when the larva exhausts its yolk reserves, moves away from its nest and out into the big wide sea. It immediately begins preying on organisms smaller than a grain of sand.

Although they accelerate their arms almost 100 times faster than a Formula One car, Philippine mantis shrimp larvae are slower ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Land productivity could be greatly increased by combining sheep grazing and solar energy production on the same land, according to new research by Oregon State University scientists.

This is believed to be the first study to investigate livestock production under agrivoltaic systems, where solar energy production is combined with agricultural production, such as planting agricultural crops or grazing animals.

The researchers compared lamb growth and pasture production in pastures with solar panels and traditional open pastures. They found less overall but higher quality forage in the solar pastures and that lambs raised in each pasture type ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- The Mayo Clinic data scientists who developed highly accurate computer modeling to predict trends for COVID-19 cases nationwide have new research that shows how important a high rate of vaccination is to reducing case numbers and controlling the pandemic.

Vaccination is making a striking difference in Minnesota and keeping the current level of positive cases from becoming an emergency that overwhelms ICUs and leads to more illness and death, according to a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The study, entitled "Quantifying the Importance of COVID-19 Vaccination to Our Future Outlook," outlines how Mayo's COVID-19 predictive modeling can assess future trends based on the pace of vaccination, and how vaccination trends are crucial ...

Venus is an enigma. It's the planet next door and yet reveals little about itself. An opaque blanket of clouds smothers a harsh landscape pelted by acid rain and baked at temperatures that can liquify lead.

Now, new observations from the safety of Earth are lifting the veil on some of Venus' most basic properties. By repeatedly bouncing radar off the planet's surface over the last 15 years, a UCLA-led team has pinned down the precise length of a day on Venus, the tilt of its axis and the size of its core. The findings are published today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"Venus is our sister planet, and yet these fundamental properties have remained unknown," said Jean-Luc Margot, a UCLA professor of Earth, planetary and space sciences who led the research.

Earth ...

Immunotherapies that fight cancer have been a life-saving advancement for many patients, but the approach only works on a few types of malignancies, leaving few treatment options for most cancer patients with solid tumors. Now, in two related papers published April 28, 2021 in Science Translational Medicine, researchers at UCSF have demonstrated how to engineer smart immune cells that are effective against solid tumors, opening the door to treating a variety of cancers that have long been untouchable with immunotherapies.

By "programming" basic computational abilities into immune cells that are designed to attack cancer, the researchers have overcome a number of major hurdles that have kept these strategies ...

The decision to donate to a charity is often driven by emotion rather than by calculated assessments based on how to make the biggest impact. In a review article published on April 29 in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences, researchers look at what they call "the psychology of (in)effective altruism" and how people can be encouraged to direct their charitable contributions in ways that allow them to get more bang for the buck--and help them to have a larger influence.

"In the past, most behavioral science research that's looked at charitable giving has focused on quantity and how people might be motivated to give more money to charity, or to give at all," says first author Lucius Caviola (@LuciusCaviola), a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Psychology at Harvard University. ...

Scientists in China have developed a small, flexible device that can convert heat emitted from human skin to electrical power. In their research, presented April 29 in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science, the team showed that the device could power an LED light in real time when worn on a wristband. The findings suggest that body temperature could someday power wearable electronics such as fitness trackers.

The device is a thermoelectric generator (TEG) that uses temperature gradients to generate power. In this design, researchers use the difference between the warmer body temperature and the relatively cooler ambient environment to generate power.

"This is a field with great potential," says corresponding author Qian Zhang of Harbin ...

It may seem like an unusual place to go looking for answers, but the contents of a baby's first diaper can reveal a lot about a newborn's future health.

In a new study published today in Cell Reports Medicine, a team of University of British Columbia (UBC) researchers has shown that the composition of a baby's first poop--a thick, dark green substance known as meconium--is associated with whether or not a child will develop allergies within their first year of life.

"Our analysis revealed that newborns who developed allergic sensitization by one year of age had significantly less 'rich' meconium at birth, compared to those who didn't develop allergic sensitization," says the study's senior co-author Dr. Brett Finlay, a professor at the Michael Smith ...