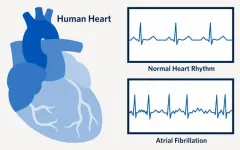

(Press-News.org) A UBC Okanagan researcher is urging people to learn and then heed the symptoms of Atrial Fibrillation (AF). Especially women.

Dr. Ryan Wilson, a post-doctoral fellow in the School of Nursing, says AF is the most commonly diagnosed arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) in the world. Despite that, he says many people do not understand the pre-diagnosis symptoms and tend to ignore them. In fact, 77 per cent of the women in his most recent study had experienced symptoms for more than a year before receiving a diagnosis.

While working in a hospital emergency department (ED), Dr. Wilson noted that many patients came in with AF symptoms that included, but were not limited to, shortness of breath, feeling of butterflies (fluttering) in the chest, dizziness or general fatigue. Many women also experienced gastrointestinal distress or diarrhea. When diagnosed they admitted complete surprise -- even though they had been experiencing the symptoms for a considerable time.

One in four strokes are AF related, he says. However, when people with AF suffer a stroke, their outcomes are generally worse than people who have suffered a stroke for other reasons.

"I would see so many patients in the ED who had just suffered a stroke but they had never been diagnosed with AF. I wanted to get a sense of their experience before diagnoses: what did they do before they were diagnosed, how they made their decisions, how they perceived their symptoms and ultimately, how they responded."

Even though his study group was small, what he learned was distressing.

"Ten women, in comparison to only three men, experienced symptoms greater than one year," says Dr. Wilson. "What's really alarming is they also had more significant severity and frequency of their symptoms than men--yet they experience the longest amount of time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis."

What really troubles Dr. Wilson are the reasons a diagnosis is delayed in women.

Many doubted their symptoms were serious, he says. They discounted them because they were tired, stressed, thought they related to other existing medical conditions, or even something they had eaten. Most women also had caregiving responsibilities that took precedence over their own health, and they chose to self-manage their symptoms by sitting, lying down, or breathing deeply until they stopped.

What's more alarming, however, is that if women mentioned their symptoms to their family doctor, many said they simply felt dismissed.

"There was a lot more anger among several of the women because they had been told nothing was wrong by their health-care provider," says Dr. Wilson. "To be repeatedly told there is nothing wrong, and then later find yourself in the emergency room with AF, was incredibly frustrating for these women. More needs to be done to support gender-sensitive ways to promote an early diagnosis regardless of the gender."

Dr. Wilson reports that none of the men in his study were upset about their interactions with their health-care providers, mostly because they were immediately sent for diagnostic tests.

"But a delay in diagnosis is not just in this study," he cautions. "Women generally wait longer than men for diagnosis with many ailments. Sadly, with AF and other critical illnesses, the longer a person waits, the shorter time there is to receive treatments. Statistically, women end up with a worse quality of life."

Dr. Wilson, who is currently working on specific strategies to help people manage AF, admits the condition is often hard to diagnose because some of the symptoms are vague. Ideally, he would like people to be as knowledgeable about AF as they are about the symptoms and risks of stroke and heart attacks. As the population is living longer, the number of people with AF continues to increase. In fact, about 15 percent of people over the age of 80 will be diagnosed with the condition.

"People know what to do for other cardiovascular diseases, it's not the same with AF," he adds. "And while the timeline may not be as essential as a stroke for diagnosis and care, there is still a substantial risk of life-limiting effects such as stroke, heart failure and dementia. Reason enough, I hope, for people to seek out that diagnosis."

INFORMATION:

Dr. Wilson's study was recently published in the Western Journal of Nursing Research.

Seeing through smog and fog. Mapping out a person's blood vessels while monitoring heart rate at the same time--without touching the person's skin. Seeing through silicon wafers to inspect the quality and composition of electronic boards. These are just some of the capabilities of a new infrared imager developed by a team of researchers led by electrical engineers at the University of California San Diego.

The imager detects a part of the infrared spectrum called shortwave infrared light (wavelengths from 1000 to 1400 nanometers), which is right outside of the visible spectrum (400 to 700 nanometers). Shortwave infrared imaging is not to be confused with thermal imaging, which detects much longer infrared wavelengths ...

A new Tel Aviv University study has revealed, for the first time, that bats know the speed of sound from birth. In order to prove this, the researchers raised bats from the time of their birth in a helium-enriched environment in which the speed of sound is higher than normal. They found that unlike humans, who map the world in units of distance, bats map the world in units of time. What this means is that the bat perceives an insect as being at a distance of nine milliseconds, and not one and a half meters, as was thought until now.

The Study was published in PNAS.

In order to determine ...

PULLMAN, Wash. -- A count of the Western Monarch butterfly population last winter saw a staggering drop in numbers, but there are hopeful signs the beautiful pollinators are adapting to a changing climate and ecology.

The population, counted by citizen scientists at Monarch overwintering locations in southern California, dropped from around 300,000 three years ago to just 1,914 in 2020, leading to an increasing fear of extinction. However, last winter large populations of monarchs were found breeding in the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas. Prior to last winter, it was unusual to find winter breeding by monarchs ...

The idea of deriving health benefits from live microorganisms is well known, but some non-living microorganisms, too, can have beneficial health effects. Yet even with an increasing number of scientific papers published on non-viable microbes for health, the category is not well defined and different terms are used in different contexts.

Now, a group of international experts has clarified this concept in a recently END ...

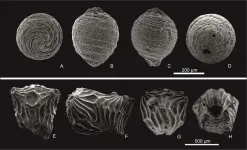

A study published in Cretaceous Research expands the paleontological richness of continental fossils of the Lower Cretaceous with the discovery of a new water plant (charophytes), the species Mesochara dobrogeica. The study also identifies a new variety of carophytes from the Clavator genus (in particular, Clavator ampullaceus var. latibracteatus) and reveals a set of paleobiographical data from the Cretaceous much richer than other continental records such as dinosaurs'.

Among the authors of the study are Josep Sanjuan, Alba Vicente, Jordi Pérez-Cano and Carles Martín-Closas, members of the Faculty of Earth Sciences and the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBio) of the University of Barcelona, in collaboration with the expert Marius Stoica, ...

Ishikawa, Japan - Inside our cells, and those of the most well-known lifeforms, exist a variety of complex compounds known as "molecular motors." These biological machines are essential for various types of movement in living systems, from the microscopic rearrangement or transport of proteins within a single cell to the macroscopic contraction of muscle tissues. At the crossroads between robotics and nanotechnology, a goal that is highly sought after is finding ways to leverage the action of these tiny molecular motors to perform more sizeable tasks in a controllable manner. However, achieving this goal will certainly be challenging. "So far, even though researchers ...

Singapore, 5 May 2021 - The rapid advancement of Autonomous Vehicles (AV) technology in recent years has changed transport systems and consumer habits globally. As countries worldwide see a surge in AV usage, the rise of shared Autonomous Mobility on Demand (AMoD) service is likely to be next on the cards. Public Transit (PT), a critical component of urban transportation, will inevitably be impacted by the upcoming influx of AMoD and the question remains unanswered on whether AMoD would co-exist with or threaten the PT system.

Researchers at the Future Urban Mobility (FM) Interdisciplinary Research Group (IRG) at Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), MIT's research enterprise in Singapore, and Massachusetts ...

The inner workings of a "self-destruct switch" present on human cells that can be activated during an immune response have been revealed. In unprecedented detail, KAUST scientists with collaborators in China report the 3D atomic structure of the human PANX1 protein, which may help underpin new therapies that target the immune system.

When cells become infected with a pathogen, the body's immune system works to destroy the infected cells before they become a threat to surrounding tissues. This form of cell death, during which a cell releases potent ...

The first civilisations to build monumental palaces and urban centres in Europe are more genetically homogenous than expected, according to the first study to sequence whole genomes gathered from ancient archaeological sites around the Aegean Sea. The study has been published in the journal Cell.

Despite marked differences in burial customs, architecture, and art, the Minoan civilization in Crete, the Helladic civilization in mainland Greece and the Cycladic civilization in the Cycladic islands in the middle of the Aegean Sea, were genetically similar during the Early Bronze age ...

We live in times when among the most limited and precious resources on Earth are air and water. No matter the geographical location, the pollution spreads quickly, negatively affecting even the purest regions like Mount Everest. Thus, anthropogenic activity decreases the quality of the environment, making it harmful for flora and fauna. Current waste treatment methods are not sufficient, so novel and effective methods for maximizing pollutants removal are highly needed. One of the robust and prosperous solutions that make it possible to degrade various highly toxic chemicals from air and water is based on nanotechnology. Nanomaterials offer unique physicochemical properties, ...