(Press-News.org) Researchers at the University of California San Diego have laid the groundwork for a potential new type of gene therapy using novel CRISPR-based techniques.

Working in fruit flies and human cells, research led by UC San Diego Postdoctoral Scholar Zhiqian Li in Division of Biological Sciences Professor Ethan Bier's laboratory demonstrates that new DNA repair mechanisms could be designed to address the effects of debilitating diseases and damaged cell conditions.

The scientists developed a novel genetic sensor called a "CopyCatcher," which capitalizes on CRISPR-based gene drive technology, to detect instances in which a genetic element is copied precisely from one chromosome to another throughout cells in the body of a fruit fly.

Details are explained in the journal Nature Communications.

Gene-drive technology is being developed to copy and distribute desired traits in reproductive cells of the body (sperm and eggs), which allows these traits to be spread throughout populations--potentially preventing transmission of insect-vectored diseases such as malaria and fortifying agricultural crops. For human health applications, next-generation CopyCatcher systems will measure how often such perfect copying might take place in different cells of the human body. As this system detects a very high rate of copying in fruit flies, similar success in human cells would allow scientists to make desired precise genome edits throughout the body, and particularly in cells that rely on the function of that gene for normal health.

"These studies provide a clear proof of principle for a new type of gene therapy in which one copy of a mutated gene could be repaired from a partially intact second copy of the gene," said Bier, senior author of the Nature Communications study and science director for the Tata Institute for Genetics and Society-UC San Diego. "The need for such a design occurs in genetic situations with patients with inherited genetic disorders, if their parents were carriers for two different mutations in the same gene."

Bier says the strategy of fixing a mutated gene in its normal context within the genome differs greatly from current gene therapy strategies in which a surrogate copy of a gene is placed at a different site in the genome and acts as a crude "patch."

"This method restores enough gene activity to allow the patient to limp by," said Bier. "In these cases, genes are often activated in cells where they should normally be silent and may not be activated in others where they should be."

If the high efficiency of precise in vivo gene editing detected by CopyCatchers in fruit flies could be achieved in human cells, then a variety of genetic disorders might be treated including blood diseases, diseases affecting vision or hearing and diseases targeting specific organs such as muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis (lung and kidney) and congenital heart defects.

"This restorative form of gene therapy would represent a major improvement over existing methods in which a functional copy of the gene is typically activated in all cells of the body but in an abnormal pattern," said Li.

Although the researchers detected highly efficient copying of genetic information in three genes active in different tissues of the fly body (eyes, epidermis and embryonic cells), this ability to copy information from one chromosome to another was less efficient in human cells (4-8% of cells) than in flies (in 30-50% of cells), the researchers found. However, in human cells where specific cuts were made to one chromosome using CRISPR, the researchers rigorously established that the other chromosome could be used to repair the damage resulting in a genetic element being precisely copied into the cut site. Moreover, measures to improve copying in flies also translated to enhanced copying in human cells suggesting that further research may increase the efficiency of human in vivo genetic repair.

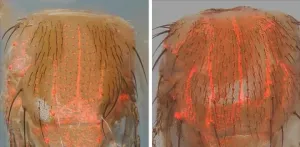

CopyCatchers are designed based on the fact that cells have two copies of each chromosome. In its starting location, a CopyCatcher is rendered inactive, preventing it from producing a red fluorescent detector protein. If the CopyCatcher copies itself precisely to the other chromosome, however, then it can free itself from the constraint imposed on the original element thereby leading to cells becoming fluorescent. The fraction of red fluorescing cells tabulated throughout a tissue is a quantitative indicator of the frequency of precise CRISPR editing. Since cells of the body have been thought to be relatively recalcitrant to precise CRISPR editing, it was surprising that CopyCatchers reveal an unexpected potential of cells throughout the body to do so, such as in the eyes and in the epidermis.

In the next series of planned experiments Li and colleagues in the Bier lab will use CopyCatchers and related systems to further optimize the efficiency of corrective editing and develop model systems for human diseases to enhance the efficacy this technology for gene therapy applications.

INFORMATION:

The co-authors of the study include: Zhiqian Li, Nimi Marcel, Sushil Devkota, Ankush Auradkar, Stephen Hedrick, Valentino Gantz and Ethan Bier.

The research was funded by National Institutes of Health (grant R01 GM117321), a Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group Distinguished Investigators Award and a gift from the Tata Trusts in India to TIGS-UC San Diego and TIGS-India.

Note: Bier has equity interest in two companies he co-founded: Synbal Inc. and Agragene, Inc., which may potentially benefit from the research results. He also serves on Synbal's board of directors and the scientific advisory board for both companies.

Researchers at the University of Bristol have discovered how microbes responsible for human African sleeping sickness produce sex cells.

In these single-celled parasites, known as trypanosomes, each reproductive cell splits off in turn from the parental germline cell, which is responsible for passing on genes. Conventional germline cells divide twice to produce all four sex cells - or gametes - simultaneously. In humans four sperms are produced from a single germline cell. So, these strange parasite cells are doing their own thing rather than sticking to ...

Every high-school physics student learns that sound and light travel at very different speeds. If the brain did not account for this difference, it would be much harder for us to tell where sounds came from, and how they are related to what we see.

Instead, the brain allows us to make better sense of our world by playing tricks, so that a visual and a sound created at the same time are perceived as synchronous, even though they reach the brain and are processed by neural circuits at different speeds.

One of the brain's tricks is temporal recalibration: ...

A novel technique for studying vortices in quantum fluids has been developed by Lancaster physicists.

Andrew Guthrie, Sergey Kafanov, Theo Noble, Yuri Pashkin, George Pickett and Viktor Tsepelin, in collaboration with scientists from Moscow State University, used tiny mechanical resonators to detect individual quantum vortices in superfluid helium.

Their work is published in the current volume of Nature Communications.

This research into quantum turbulence is simpler than turbulence in the real world, which is observed in everyday phenomena such as surf, fast flowing rivers, billowing storm clouds, or chimney smoke. Despite ...

Scientists at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa (CBM-CSIC-UAM) have discovered that the nitric oxide (NO) pathway is overactivated in the aortas of mice and patients with Marfan Syndrome and that the activity of this pathway causes the aortic aneurysms that characterize this disease.

The results of the study, published today in Nature Communications, reveal the essential role played by NO in Marfan Syndrome aortic disease and identify new therapeutic targets and markers of NO pathway activation that could be used to monitor disease status and progression.

Aortic aneurysm ...

A new paper in the Journal of the European Economic Association, published by Oxford University Press, indicates that distrust generated by a 2011 CIA-led vaccination campaign ruse designed to catch Osama Bin Laden resulted in a significant vaccination rate decline in Pakistan.

Using a local doctor, the US Central Intelligence Organization planned an immunization plan in Pakistan to obtain DNA samples of children living in a compound in Abbottabad where American authorities suspected Bin Laden was hiding in order to obtain proof of Bin Laden's location (because the presence of close ...

About 42% of rural school districts in the U.S. offered fully in-person instruction as of February, compared with only 17% for urban districts, according to a new RAND Corporation survey of school district leaders. The opposite pattern held for fully remote learning: 29% of urban districts offered fully remote instruction compared with 10% of rural districts and 18% of suburban districts.

The choice of in-person versus remote learning has important implications. Over a third of all U.S. school districts offering some form of remote instruction in early 2021 had shortened the school day, and a quarter had reduced instructional minutes.

"This survey shows how the choice of remote instruction has ramifications that extend beyond longstanding concerns about ...

Aqueducts are very impressive examples of the art of construction in the Roman Empire. Even today, they still provide us with new insights into aesthetic, practical, and technical aspects of construction and use. Scientists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) investigated the longest aqueduct of the time, the 426-kilometer-long Aqueduct of Valens supplying Constantinople, and revealed new insights into how this structure was maintained back in time. It appears that the channels had been cleaned of carbonate deposits just a few decades before the ...

Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, have developed a new material that prevents infections in wounds - a specially designed hydrogel, that works against all types of bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant ones. The new material offers great hope for combating a growing global problem.

The World Health Organization describes antibiotic-resistant bacteria as one of the greatest threats to global health. To deal with the problem, there needs to be a shift in the way we use antibiotics, and new, sustainable medical technologies must be developed.

"After testing our new hydrogel on different types of bacteria, we observed a high level of effectiveness, including against those ...

In some countries of the WHO European Region, 1 in 3 children aged 6 to 9 years is living with overweight or obesity. Mediterranean countries have the highest rates of obesity, but the situation there is starting to improve.

These are some of the findings of a new WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) report on the fourth round of data collection (2015-2017), presented at this week's European Congress on Obesity (held online this year). The report gives the latest data available on 6- to 9-year-olds in 36 countries in the region. A questionnaire collecting ...

New research presented at this year's European Congress on Obesity (held online, 10-13 May) shows that fat around the waist (abdominal obesity) is more important than general obesity as shown by body mass index (BMI) in predicting the severity of chest X-ray results in patients with COVID-19. The study is by Dr Alexis Elias Malavazos, I.R.C.C.S.Policlinico San Donato, San Donato Milanese, Italy, and colleagues.

Previous research has established that both chest x-ray (CXR) severity score and obesity are predictive risk factors for COVID-19 hospital admission. However, the relationship between abdominal obesity and CXR severity score is not fully explored. This retrospective cohort study analysed the association of different methods of measuring obesity, ...