(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

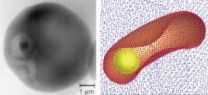

Malaria-infected red blood cells can be 50 times stiffer and have surface changes that disrupt the smooth flow of blood, depriving the brain and other organs of nutrients and oxygen....

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Although the incidence of malaria has declined in all but a few countries worldwide, according to a World Health Organization report earlier this month, malaria remains a global threat. Nearly 800,000 people succumbed to the mosquito-borne disease in 2009, nearly all of them in the developing world.

Physicians do not have reliable treatment for the virus at various stages, largely because no one has been able to document the malaria parasite's journeys in the body.

Now researchers at Brown University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have used advanced computer modeling and laboratory experiments to show how malaria parasites change red blood cells and how the infected cells impede blood flow to the brain and other critical organs.

Their findings, published in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could help doctors chart, in real time, the buildup in the body of cells infected with malaria or other diseases (such as sickle-cell anemia) and to prescribe treatment accordingly.

"The idea is to predict the evolution of these diseases, just like we predict the weather," said George Karniadakis, professor of applied mathematics at Brown and corresponding author on the paper.

The researchers worked with Plasmodium falciparum, a parasite that can cause cerebral malaria by lodging in capillaries of the brain, especially among children. The parasite is found globally but is most common in Africa.

Once introduced into the human body by an infected mosquito's bite, the parasite invades red blood cells. Healthy red blood cells are tremendously elastic; even though they can reach 8 microns in length and 2 microns in thickness, they can easily slide through a capillary just 3 microns in diameter. Capillaries are vital conduits in the human brain and other organs; red blood cells are key transporters of oxygen and nutrients.

Through extensive modeling carried out on one of the world's fastest supercomputers at the National Institute for Computational Sciences, Karniadakis and colleagues found that malaria-infected red blood cells stiffened as much as 50 times more than healthy red blood cells. The result: Infected red blood cells, having lost their elasticity, could no longer pass through capillaries, effectively blocking them.

"Basically what happens is the brain could be deprived of nutrients and oxygen," said Karniadakis, a member of the Center for Fluid Dynamics, Turbulence and Computation at Brown. "This happens because of the deformation of these red blood cells.

"This shows that as stiffening increases (in red blood cells), the viscosity of the blood increases, and the heart has to pump twice as much sometimes to get the same blood flow," Karniadakis added.

The researchers also found that infected red blood cells had a tendency to stick, flip, and flop along the walls of blood vessels — unlike healthy blood cells that flow in the middle of the channel. For reasons not entirely known, the infected red blood cells develop little knobby protrusions on their cellular skin that tend to stick to the surface of the blood wall, known as the endothelium. Scientists call the sticking cytoadhesion.

"So, what happens is the infected red blood cell is not only stiffer, it's slowed down by this interaction (cytoadhesion)," Karniadakis said. "This drastically changes the flow of blood in the brain, especially in the arterials and in the capillaries."

INFORMATION:

Dimitry Fedosov, first author on the paper, worked on the research as a graduate student at Brown. He is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Solid State Research in Germany. Bruce Caswell, professor emeritus in the School of Engineering at Brown, contributed to the research. Subra Suresh, former dean of the engineering school at MIT and now director of the National Science Foundation, also contributed to the research.

The National Institutes of Health and the NSF funded the research.

Malaria-infected cells stiffen, block blood flow

2010-12-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Intensive chemotherapy can dramatically boost survival of older teenage leukemia patients

2010-12-21

More effective risk-adjusted chemotherapy and sophisticated patient monitoring helped push cure rates to nearly 88 percent for older adolescents enrolled in a St. Jude Children's Research Hospital acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treatment protocol and closed the survival gap between older and younger patients battling the most common childhood cancer.

A report online in the December 20 edition of the Journal of Clinical Oncology noted that overall survival jumped 30 percent in the most recent treatment era for ALL patients who were age 15 through 18 when their cancer ...

Waterways contribute to growth of potent greenhouse gas

2010-12-21

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, has increased by more than 20 percent over the last century, and nitrogen in waterways is fueling part of that growth, according to a Michigan State University study.

Based on this new study, the role of rivers and streams as a source of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere now appears to be twice as high as estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, according to Stephen Hamilton, a professor at MSU's Kellogg Biological Station. The study appears in the current issue of the Proceedings of the Academy ...

New breathing therapy reduces panic and anxiety by reversing hyperventilation

2010-12-21

VIDEO:

A new breathing therapy reduces panic and anxiety by reversing hyperventilation. The breakthrough "CART " treatment, developed by SMU psychologist Alicia E. Meuret, worked better than traditional cognitive therapy at altering...

Click here for more information.

A new treatment program teaches people who suffer from panic disorder how to reduce the terrorizing symptoms by normalizing their breathing.

The method has proved better than traditional cognitive ...

Quitting menthol cigarettes may be harder for some smokers

2010-12-21

Menthol cigarettes may be harder to quit, particularly for some teens and African-Americans, who have the highest menthol cigarette use, according to a study by a team of researchers.

Recent studies have consistently found that racial/ethnic minority smokers of menthol cigarettes have a lower quit rate than comparable smokers of regular cigarettes, particularly among younger smokers.

One possible reason suggested in the report is that the menthol effect is influenced by economic factors -- less affluent smokers are more affected by price increases, forcing them to consume ...

The genetic basis of brain diseases

2010-12-20

In research published today, scientists have studied human brain samples to isolate a set of proteins that accounts for over 130 brain diseases. The paper also shows an intriguing link between diseases and the evolution of the human brain.

Brain diseases are the leading cause of medical disability in the developed world according to the World Health Organisation and the economic costs in the USA exceeds $300 billion.

The brain is the most complex organ in the body with millions of nerve cells connected by billions of synapses. Within each synapse is a set of proteins, ...

Scientists decipher 3 billion-year-old genomic fossils

2010-12-20

About 580 million years ago, life on Earth began a rapid period of change called the Cambrian Explosion, a period defined by the birth of new life forms over many millions of years that ultimately helped bring about the modern diversity of animals. Fossils help palaeontologists chronicle the evolution of life since then, but drawing a picture of life during the 3 billion years that preceded the Cambrian Period is challenging, because the soft-bodied Precambrian cells rarely left fossil imprints. However, those early life forms did leave behind one abundant microscopic fossil: ...

CSHL study finds that 2 non-coding RNAs trigger formation of a nuclear subcompartment

2010-12-20

Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – The nucleus of a cell, which houses the cell's DNA, is also home to many structures that are not bound by a membrane but nevertheless exist as distinct compartments. A team of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) scientists has discovered that the formation of one of these nuclear subcompartments, called paraspeckles, is triggered by a pair of RNA molecules, which also maintain its structural integrity.

As reported in a study published online ahead of print on December 19 in Nature Cell Biology, the scientists discovered this unique structure-building ...

Increased Consumer Demand for BBQ Brisket Fuels Sadler's Smokehouse's Growth

2010-12-20

the growing popularity of barbecue across the U.S. in 2010 has boosted sales and distribution, announces Sadler's Smokehouse, Ltd., North America's leader in premium, pit-smoked meats. Retail and club distribution has increased to more than 7,000 stores, and year-to-date sales of brisket, dinners and other Sadler's products are up 15 percent in this channel.

Traditionally a regional favorite in the south, smoked brisket is gaining popularity throughout the U.S. as consumers from coast to coast are adding it to their weekly menus. To meet the demand, the company has ...

Eswaran Brothers is the First Tea Company in the World to be Certified CarbonNeutral

2010-12-20

Eswaran Brothers Exports announced that it has achieved CarbonNeutral company certification, a major milestone in the sixty-seven year history of the family-owned tea company.

The Vice Chairman of Eswaran Brothers and a third generation tea taster, Mr. Subramaniam Eassuwaren, stated, "As part of a family that has been devoted to tea, this is an important landmark for us. It's among the initial steps we have taken in our drive to become a truly ethical and sustainable business while still maintaining profitability. It is also an extension of our heritage and values that ...

New tropical mistletoe described just in time for Christmas

2010-12-19

As the UN's International Year of Biodiversity draws to a close, scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew are celebrating the diversity of the planet's plant and fungal life by highlighting some of the weird, wonderful and stunning discoveries they've made this year from the rainforests of Cameroon to the UK's North Pennines. But it's not just about the new – in some cases species long thought to be extinct in the wild have been rediscovered.

Professor Stephen Hopper, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew says, "Each year, botanists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, ...