(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. - Free from human disturbance for a century, an inland island in Central America has nevertheless lost more than 25% of its native bird species since its creation as part of the Panama Canal's construction, and scientists say the losses continue.

The Barro Colorado Island extirpations show how forest fragmentation can reduce biodiversity when patches of remnant habitat lack connectivity, according to a study by researchers at Oregon State University.

Even when large remnants of forest are protected, some species still fail to survive because of subtle environmental changes attributable to fragmentation, and those losses continue over many decades, the scientists say.

Findings, published this week in Scientific Reports, suggest that the island's bird population is "drying out" - i.e., taking on community characteristics associated with less damp parts of central Panama.

Barro Colorado Island, or BCI, is a 6-square-mile former hilltop jutting from manmade Gatun Lake, created when the Chagres River was dammed as part of the canal project more than 100 years ago. The lake is a primary component of the canal, and the island was set aside as a nature reserve in 1923 by the United States, which then controlled the canal zone.

BCI is probably the best-case example for conservation of tropical diversity in fragmented landscapes, according to Doug Robinson, the Mace Professor of Watchable Wildlife in OSU's College of Agricultural Sciences. BCI's surrounding habitats are stable over long periods of time, it is protected from hunting, and there is no resource extraction such as tree harvesting.

BCI is also home to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, which calls the island the world's most intensively studied tropical forest. Yet BCI is still losing species even after 100 years of protection.

"BCI has been a model system to study species losses such as the ones we report on in this paper," Robinson said. "The island is unique in that it has been visited by ornithologists since the 1920s, so we have a rare record of inventories spanning the last century. No other tropical site has been studied so long."

Forests in the tropics display extreme biological diversity, Robinson notes, adding the highest bird diversity on the globe is in tropical America. Tropical landscapes, however, have undergone rapid change through large-scale deforestation, which means habitat loss as well as a lack of connectivity among the forest patches that remain.

"Species disappear from these isolated habitat remnants, but the losses are not immediate nor are the causes of the losses obvious," said Robinson, who has been doing research on the island for 27 years. "Some of the species disappearances take more than 100 years to materialize and our understanding of the erosion of diversity is in many locations hampered by a lack of tropical studies that span more than a few decades."

Collaborator Jenna Curtis is a staff member at Cornell University who earned a Ph.D. at Oregon State while working with Robinson. She used the century-long record of bird inventories from BCI and parts of the data Robinson and collaborators have been collecting since 1994 to ask questions about what factors might explain species losses in forest fragments.

In the case of BCI, 27% of the 228 bird species initially found on the island have disappeared, though all are still present in the bigger forest parcels that ring Gatun Lake. Thirty-seven forest-associated species have disappeared despite increasing forest coverage on the island.

To hone-in on the losses among forest-associated resident birds, the study excluded aquatic species, vagrants and non-breeding migrants, as well as birds that forage in the air like vultures, swifts, swallows and nighthawks, whose daily ranges extend well beyond BCI.

"We examined some previously recognized factors that could help explain the risk of extinction, such as initial population size in the remnant patch and traits like preference for certain foods and foraging locations and nest height and type," Curtis said. "The novel result we identified was that species living in the wettest forests of central Panama were most likely to have disappeared from the island - now the bird community on BCI looks more like a community that you'd find in the less rainy locations in central Panama. Changes in the bird community therefore reflect the idea that the BCI bird community is drying out, even though rainfall itself hasn't changed."

The group of scientists, which also included Ghislain Rompre? and Randall Moore of OSU's Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences and Bruce McCune of the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, could detect that trend because of the exhaustive surveys, led by Robinson, of birds across central Panama, which has a range of local annual rainfalls.

"The north, the Caribbean coast, is very wet with more than 3 meters of rain per year," he said. "The Pacific coast on the south is relatively dry. The bird communities in the 24 regions we've surveyed are quite different, showing that we could use the rainfall gradient as a way to index habitat preferences of the birds. The birds that live in the wet forests near the north coast were much more likely to have disappeared from BCI than species that can tolerate dry forests."

When habitat remnants are connected with other patches of undisturbed forest instead of being isolated like BCI, birds could move when conditions were too dry and return when they were more favorable, Curtis said.

"It's very easy to underappreciate the effects forest fragmentation has on tropical diversity," she said. "Even when we have large remnants that are protected from human disturbance, we still lose species because of subtle environmental changes, and those losses continue to occur over a very long time. Thus connecting forest remnants will be very important for the long-term preservation of tropical bird diversity."

INFORMATION:

Funding this study were the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation Oregon Chapter, the Oregon Lottery, Thomas G. Scott, the Coombs-Simpson Memorial Fellowship and the OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences.

DALLAS - May 12, 2021 - Scientists with UT Southwestern's Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute have identified the molecular mechanism that can cause weight gain for those using a common antipsychotic medication. The findings, published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, suggest new ways to counteract the weight gain, including a drug recently approved to treat genetic obesity, according to the study, which involved collaborations with scientists at UT Dallas and the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

"If this effect can be shown in clinical trials, it could give us a way to effectively treat ...

Astronomers commonly refer to massive stars as the chemical factories of the Universe. They generally end their lives in spectacular supernovae, events that forge many of the elements on the periodic table. How elemental nuclei mix within these enormous stars has a major impact on our understanding of their evolution prior to their explosion. It also represents the largest uncertainty for scientists studying their structure and evolution.

A team of astronomers led by May Gade Pedersen, a postdoctoral scholar at UC Santa Barbara's Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, have now measured the internal mixing within an ensemble of these stars using observations ...

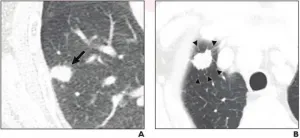

Leesburg, VA, May 13, 2021--According to an open-access Editor's Choice article in ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), CT features may help identify which patients with stage IA non-small cell lung cancer are optimal candidates for sublobar resection, rather than more extensive surgery.

This retrospective study included 904 patients (453 men, 451 women; mean age, 62 years) who underwent lobectomy (n=574) or sublobar resection (n=330) for stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Two thoracic radiologists independently evaluated findings on preoperative chest CT, later resolving any discrepancies. Recurrences were identified via medical record review.

"In patients with stage IA non-small cell lung cancer, pathologic ...

Boston - Pregnant women with symptomatic COVID-19 have a higher risk of intensive care unit admissions, mechanical ventilation and death compared to non-pregnant reproductive age women. Increases in preterm birth and still birth have also been observed in pregnancies complicated by the viral infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that people who are pregnant may choose to be vaccinated at their own discretion with their healthcare provider. However, pregnant and lactating women were not included in Phase 3 vaccine efficacy trials; thus, data on vaccine safety and immunogenicity in this population is limited.

In a new study from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), ...

Despite having been driven nearly to extinction, the California condor has a high degree of genetic diversity that bodes well for its long-term survival, according to a new analysis by University of California researchers.

Nearly 40 years ago, the state's wild condor population was down to a perilous 22. That led to inbreeding that could have jeopardized the population's health and narrowed the bird's genetic diversity, which can reduce its ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

In comparing the complete genomes of two California condors with those of an Andean condor and a turkey vulture, UC San Francisco and UC Berkeley scientists did find genetic evidence of inbreeding over the past few centuries, but, overall, a ...

TORONTO, ON - A team of evolutionary biologists from the University of Toronto has shown that Anolis lizards, or anoles, are able to breathe underwater with the aid of a bubble clinging to their snouts.

Anoles are a diverse group of lizards found throughout the tropical Americas. Some anoles are stream specialists, and these semi-aquatic species frequently dive underwater to avoid predators, where they can remain submerged for as long as 18 minutes.

"We found that semi-aquatic anoles exhale air into a bubble that clings to their skin," says Chris Boccia, a recent Master of Science graduate from the Faculty of Arts & Science's Department of Ecology ...

Traffic noise leads to inaccuracies and delays in the development of song learning in young birds. They also suffer from a suppressed immune system, which is an indicator of chronic stress. A new study by researchers of the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology and colleagues shows that young zebra finches, just like children, are particularly vulnerable to the effects of noise because of its potential to interfere with learning at a critical developmental stage.

Traffic noise is a pervasive pollutant that adversely affects the health and well-being ...

New Orleans, LA - Research conducted by an international team of scientists discovered a mechanism that leads to Herceptin resistance, representing a significant clinical obstacle to successfully treating HER2-positive breast cancer. They also identified a new approach to potentially overcome it. The work is published online in Nature Communications, available here.

"This work attempts to understand why some HER2-positive breast cancer patients do not benefit from treatment with Herceptin, which is a generally effective HER2-targeted therapy," explains Bolin Liu, MD, Professor of Genetics at LSU Health New Orleans' School of Medicine and Stanley S. Scott Cancer Center.

The researchers found increased signaling by IGF2/IRS1 (genes involved in ...

MAROANTSETRA, Madagascar (May 13, 2021) - A new study by WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society) looks at the prevalence of human consumption of lemur and fossa (Madagascar's largest predator) in villages within and around Makira Natural Park, northeastern Madagascar, providing up-to-date estimates of the percentage of households who eat meat from these protected species.

Authors from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) describe their findings in the journal Conservation Science and Practice. In Madagascar, the consumption of endangered and protected species, in particular lemurs, ...

Two recent papers from Hungarian researchers highlight the so far underrated relevance of pet dog biobanking in molecular research and introduce their initiative to make pioneering steps in this field. The Hungarian Canine Brain and Tissue Bank (CBTB) was established by the research team of the Senior Family Dog Project in 2017, following the examples of human tissue banks. In a recent paper, the team reports findings, which would not have been possible without the CBTB, and may augment further progress in dog aging and biomarker research.

Even though dogs have a much shorter average lifespan than humans, the aging path of the two species has remarkable similarities. Hence our best friends have attracted the attention ...