Researchers pinpoint possible way to prevent permanent hearing loss caused by cancer drug

Deeper understanding of how the chemotherapy drug cisplatin works in the body may potentially eliminate the toxic side-effect in childhood cancer survivors.

2021-05-14

(Press-News.org) University of Alberta scientists have identified a receptor in cells that could be key to preventing permanent hearing loss in childhood cancer survivors who are being treated with the drug cisplatin. The researchers believe by inhibiting the receptor, they may be able to eliminate toxic side-effects from the drug that cause the hearing loss.

Cisplatin is an incredibly effective chemotherapeutic when it comes to treating solid tumours in children, contributing to an 80 per cent overall survival rate over five years, according to U of A researcher Amit Bhavsar, an assistant professor in the Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology. The problem has always been with the side-effects. Nearly 100 per cent of patients who receive higher doses of cisplatin show some degree of permanent hearing loss. The ability to prevent this side-effect would dramatically improve the quality of life of childhood cancer survivors after they recover from the disease.

As Bhavsar explains, many researchers look at cisplatin's damaging side-effects from the angle of genetics, trying to determine underlying risk factors for hearing loss or examine how it works as a chemotherapeutic. A fair amount was known about the progression of hearing loss as a side-effect, but it was the initial spark--the instigating factor kicking everything off--that remained a mystery.

Bhavsar and his team thought outside the box and took things all the way back to the periodic table with their approach, getting some clues from the chemical composition of cisplatin itself and eventually identifying a particular receptor that was getting turned on.

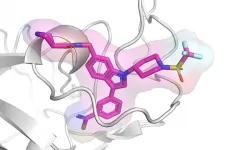

The receptor in question is Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which is involved in the body's immune response. TLR4 works by crossing the cell membrane, sticking a portion of itself outside the cell to sample the environment and to look for different signals that indicate damage or danger of some sort.

"It's a receptor that your body normally uses to detect when there's some sort of issue, like an infection. This receptor will turn on, and it'll start producing these signals that tell the cell it's under stress. Unfortunately in the case of cisplatin, those signals ultimately lead to the death of the cells responsible for hearing."

The cells affected by TLR4's signals are located within the cochlea of the ear, where they play a crucial role in hearing, translating vibrations in the ear into electrical impulses. Cisplatin also accumulates in the kidneys, but the difference is that it can be flushed out and diluted in that area of the body; in a closed system such as the ear, it accumulates and damages the cells.

"These cells don't renew. You really only get one shot and if they're gone, you're in trouble. The hearing loss is permanent," said Bhavsar.

The only way to prevent the damage is to stop the signals TLR4 produces that lead to the accumulation of cisplatin. To confirm the efficacy of inhibiting the TLR4 receptor, Bhavsar and his team looked at zebrafish models, with the help of Ted Allison, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and member of the U of A's Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute. They examined neuromasts, which are sensory cells within zebrafish that behave similarly to the human hair cells typically damaged by cisplatin. Bhavsar was able to prove that inhibiting TLR4 led to an inhibition of the damage on the sensory cells.

Bhavsar, a member of the Cancer Research Institute of Northern Alberta (CRINA), the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology and the Women and Children's Health Research Institute (WCHRI), is collaborating with CRINA member Frederick West and Allison to refine an inhibitor that can disrupt this sampling process, removing the function that causes the toxic side-effect while still keeping the immune sensor function intact so patients don't become immunocompromised.

"It really does open the door for potential therapeutics," said Bhavsar.

The study, "Toll-like receptor 4 is activated by platinum and contributes to cisplatin-induced ototoxicity," was published in EMBO Reports. The work received support through operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Stollery Children's Hospital Foundation through WCHRI, as well as funding from the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-14

Boston - While overall emergency department visits have decreased during the pandemic, nonfatal opioid overdose visits have more than doubled. However, few patients who overdosed on opioids had received a prescription for naloxone, a medication designed to block the effects of opioids on the brain and rapidly reverse opioid overdose.

In a new study, clinician-researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) analyzed naloxone prescription trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and compared them to trends in opioid prescriptions and to overall prescriptions. The team's findings, published in the journal JAMA Health Forum, suggest patents with opioid misuse disorders may be experiencing a dangerous decrease in access to the overdose-reversing ...

2021-05-14

A groundbreaking study led by engineering and medical researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how engineered immune cells used in new cancer therapies can overcome physical barriers to allow a patient's own immune system to fight tumors. The research could improve cancer therapies in the future for millions of people worldwide.

The research is published in Nature Communications, a peer-reviewed, open access, scientific journal published by Nature Research.

Instead of using chemicals or radiation, immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that helps the patient's immune system fight cancer. T cells are a type of white ...

2021-05-14

KINGSTON, R.I. - May 14, 2021 - We are frequently reminded of how vulnerable our health and safety are to threats from nature or those who wish to harm us.

New sensors developed by Professor Otto Gregory, of the College of Engineering at the University of Rhode Island, and chemical engineering doctoral student Peter Ricci, are so powerful that they can detect threats at the molecular level, whether it's explosive materials, particles from a potentially deadly virus or illegal drugs entering the country.

"This is potentially life-saving technology," said Gregory. "We have detected ...

2021-05-14

Researchers from Mosquito Alert (who belong to CEAB-CSIC, CREAF and UPF) together with researchers from the University of Budapest have shown that an artificial intelligence algorithm is capable of recognizing the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) in the photos sent by Mosquito Alert users.

The results of the study published in Scientific Reports have been obtained by applying deep learning technology or deep learning, an aspect of artificial intelligence that seeks to emulate the way of learning of humans and that has previously been used in the health field to interpret ...

2021-05-14

Of the over 400 climate scenarios assessed in the 1.5°C report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), only around 50 scenarios avoid significantly overshooting 1.5°C. Of those only around 20 make realistic assumptions on mitigation options, for instance the rate and scale of carbon removal from the atmosphere or extent of tree planting, a new study shows. All 20 scenarios need to pull at least one mitigation lever at "challenging" rather than "reasonable" levels, according to the analysis. Hence the world faces a high degree of risk of overstepping the 1.5°C limit. The realistic window for meeting the 1.5°C target is very rapidly closing.

If all climate mitigation levers are pulled, it may still be possible ...

2021-05-14

The protein made by the ASH1L gene plays a key role in the development of acute leukemia, along with other diseases. The ASH1L protein, however, has been challenging to target therapeutically.

Now a team of researchers led by Jolanta Grembecka, Ph.D., and Tomasz Cierpicki, Ph.D., from the University of Michigan has developed first-in-class small molecules to inhibit ASH1L's SET domain -- preventing critical molecular interactions in the development and progression of leukemia.

The team's findings, which used fragment-based screening, followed by medicinal chemistry and a structure-based design, appear in Nature Communications.

In mouse models of mixed lineage leukemia, the lead compound, known as AS-99, successfully reduced leukemia progression.

"This ...

2021-05-14

Organizing functional objects in a complex, sophisticated architecture at the nanoscale can yield hybrid materials that tremendously outperform their solo objects, offering exciting routes towards a spectrum of applications. The development in synthetic chemistry over past decades has enabled a library of hybrid nanostructures, such as core-shell, patchy, dimer, and hierarchical/branched ones.

Nevertheless, the material combinations of these non-van der Waals solids are largely limited by the rule of lattice-matched epitaxy.

A research team led by professor YU Shuhong at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) has reported a new class of heteronanostructures they ...

2021-05-14

After the p53 tumour suppressor gene, the genes most frequently found mutated in cancer are those encoding two proteins of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex. This complex's function is to "accommodate" the histones that cover the DNA of the chromosomes so that the processes of transcription, DNA repair and replication or chromosome segregation can occur, as appropriate. A group from the University of Seville has demonstrated at CABIMER that the inactivation of BRG1, the factor responsible for the enzymatic activity of the SWI/SNF complexes, leads to high genetic instability, a characteristic common to the vast majority of tumours.

This study's most important contribution is that it deciphers the mechanism by which this occurs. The SWI/SNF complex ...

2021-05-14

Yoga and breathing exercises have a positive effect on children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). After special classes, children improve their attention, decrease hyperactivity, they do not get tired longer, they can engage in complex activities longer. This is the conclusion reached by psychologists at Ural Federal University who studied the effect of exercise on functions associated with voluntary regulation and control in 16 children with ADHD aged six to seven years. The results of the study are published in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

"For children with ADHD, as a rule, the part of the brain that is responsible ...

2021-05-14

The COVID-19 lockdown was a catalyst for many older people to embrace technology, reconnect with friends and build new relationships with neighbours, according to University of Stirling research.

Understanding the coping mechanisms adopted by some over 60s during the pandemic will play a key role in developing interventions to help tackle loneliness, isolation and wellbeing in the future.

The study, led by the Faculty of Health Sciences and Sport, surveyed 1,429 participants - 84 percent (1,198) of whom were over 60 - and found many had adapted to video conferencing technology to increase ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers pinpoint possible way to prevent permanent hearing loss caused by cancer drug

Deeper understanding of how the chemotherapy drug cisplatin works in the body may potentially eliminate the toxic side-effect in childhood cancer survivors.