(Press-News.org) Dozens of commonly used drugs, including antibiotics, antinausea and anticancer medications, have a potential side effect of lengthening the electrical event that triggers contraction, creating an irregular heartbeat, or cardiac arrhythmia called acquired Long QT syndrome. While safe in their current dosages, some of these drugs may have a more therapeutic benefit at higher doses, but are limited by the risk of arrhythmia.

Through both computational and experimental validation, a multi-institutional team of researchers has identified a compound that prevents the lengthening of the heart's electrical event, or action potential, resulting in a major step toward safer use and expanded therapeutic efficacy of these medications when taken in combination. The team found that the compound, named C28, not only prevents or reverses the negative physiological effects on the action potential, but does not cause any change on the normal action potential when used alone at the same concentrations. The results, found through rational drug design, were published online Friday, May 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research team was led by Jianmin Cui, professor of biomedical engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis; Ira Cohen, MD, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Physiology and Biophysics, professor of medicine, and director of the Institute for Molecular Cardiology at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University; and Xiaoqin Zou, professor of physics, biochemistry, and a member of the Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center and Institute for Data Science and Informatics at the University of Missouri.

The drugs in question, as well as several that have been pulled from the market, cause a prolongation of the QT interval of the heartbeat, known as acquired Long QT Syndrome, that predisposes patients to cardiac arrhythmia and sudden death. In rare cases, Long QT also can be caused by specific mutations in genes that code for ion channel proteins, which conduct the ionic currents to generate the action potential. Although there are several types of ion channels in the heart, a change in one or more of them may lead to this arrhythmia, which contributes to about 200,000 to 300,000 sudden deaths a year, more than deaths from stroke, lung cancer or breast cancer.

The team selected a specific target, IKs, for this work because it is one of the two potassium channels that are activated during the action potential: IKr (rapid) and IKs (slow).

"The rapid one plays a major role in the action potential," said Cohen, one of the world's top electrophysiologists. "If you block it, Long QT results, and you get a long action potential. IKs is very slow and contributes much less to the normal action potential duration."

It was this difference in roles that suggested that increasing IKs might not significantly affect normal electrical activity but could shorten a prolonged action potential.

Cui, an internationally renowned expert on ion channels, and the team wanted to determine if the prolongation of the QT interval could be prevented by compensating for the change in current and inducing the Long QT Syndrome by enhancing IKs. They identified a site on the voltage-sensing domain of the IKs potassium ion channel that could be accessed by small molecules.

Zou, an internationally recognized expert who specializes in developing new and efficient algorithms for predicting protein interactions, and the team used the atomic structure of the KCNQ1 unit of the IKs channel protein to computationally screen a library of a quarter of a million small compounds that targeted this voltage-sensing domain of the KCNQ1 protein unit. To do this, they developed software called MDock to test the interaction of small compounds with a specific protein in silico, or computationally. By identifying the geometric and chemical traits of the small compounds, they can find the one that fits into the protein -- sort of a high-tech, 3D jigsaw puzzle. While it sounds simple, the process is quite complicated as it involves charge interactions, hydrogen bonding and other physicochemical interactions of both the protein and the small compound.

"We know the problems, and the way to make great progress is to identify the weaknesses and challenges and fix them," Zou said. "We know the functional and structural details of the protein, so we can use an algorithm to dock each molecule onto the protein at the atomic level."

One by one, Zou and her lab docked the potential compounds with the protein KCNQ1 and compared the binding energy of each one. They selected about 50 candidates with very negative, or tight, binding energies.

Cui and his lab then identified C28 using experiments out of the 50 candidates identified in silico by Zou's lab. They validated the docking results by measuring the shift of voltage-dependent activation of the IKs channel at various concentrations of C28 to confirm that C28 indeed enhances the IKs channel function. They also studied a series of genetically modified IKs channels to reveal the binding of C28 to the site for the in silico screening.

Cohen and his lab tested the C28 compound in ventricular myocytes from a small mammal model that expresses the same IKs channel as humans. They found that C28 could prevent or reverse the drug-induced prolongation of the electrical signals across the cardiac cell membrane and minimally affected the normal action potentials at the same dosage. They also determined that there were no significant effects on atrial muscle cells, an important control for the drug's potential use.

"We are very excited about this," Cohen said. "In many of these medications, there is a concentration of the drug that is acceptable, and at higher doses, it becomes dangerous. If C28 can eliminate the danger of inducing Q-T prolongation, then these drugs can be used at higher concentrations, and in many cases, they can become more therapeutic."

While the compound needs additional verification and testing, the researchers say there is tremendous potential for this compound or others like it and could help to convert second-line drugs into first-line drugs and return others to the market. With assistance from the Washington University Office of Technology Management, they have patented the compound, and Cui has founded a startup company, VivoCor, to continue to work on the compound and others like it as potential drug candidates. The work was accelerated by a Leadership and Entrepreneurial Acceleration Program (LEAP) Inventor Challenge grant Washington University in St. Louis in 2018 funded by the Office of Technology Management, the Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, the Center for Drug Discovery, the Center for Research Innovation in Biotechnology, and the Skandalaris Center for Interdisciplinary Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

"This work was done by an effective drug design approach: identifying a critical site in the ion channel based on understanding of structure-function relation, using in silico docking to identify compounds that interact with the critical site in the ion channel, validating functional modulation of the ion channel by the compound, and demonstrating therapeutic potential in cardiac myocytes," Zou said. "Our three labs form a great team, and without any of them, this would not be possible."

INFORMATION:

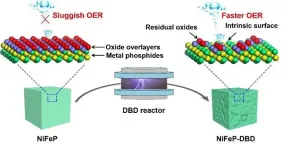

Extracting hydrogen from water through electrolysis offers a promising route for increasing the production of hydrogen, a clean and environmentally friendly fuel. But one major challenge of water electrolysis is the sluggish reaction of oxygen at the anode, known as the oxygen evolution reaction (OER).

A collaboration between researchers at Hunan University and Shenzhen University in China, has led to a discovery that promises to improve the OER process. In their recent paper, published in the KeAi journal Green Energy & Environment, they report that etching - or, in other words, chemically removing - the oxide overlayers that form on the surface of the metal phosphide electrocatalysts regularly used in electrolysis, can increase ...

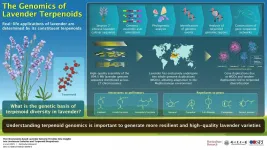

Even the mention of lavender evokes the distinct fragrance of the flower. This beautiful flower has been used to make perfumes and essential oils since time immemorial. The aesthetics of the flower have captured the imagination of hundreds, worldwide. So, what makes this flower so special? What are the "magical" compounds that gives it its unique fragrance? What is the genetic basis of these compounds? These questions have long puzzled scientists.

To find out the answers, a group of scientists from China have sequenced the genome of lavender, which is known in the scientific world as Lavandula angustifolia. The team headed by Dr. Lei Shi, Professor at the Key Laboratory of Plant Resources and Beijing Botanical Garden, Institute of Botany, Chinese ...

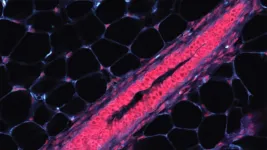

What if you could predict which cells might become cancerous? Breast tissue changes dramatically throughout a woman's life, so finding markers for sudden changes that can lead to cancer is especially difficult. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Associate Professor Camila dos Santos and her team identified and cataloged thousands of normal human and mouse breast cell types. The new catalog redefines healthy breast tissue so that when something goes awry, scientists can pinpoint its origin.

Any breast cell could become cancerous. Dos Santos says:

"To understand breast cancer risk, you have to understand normal breast cells first, so when we think about preventive and even targeting therapies, ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - In a large-animal study, researchers have shown that heart attack recovery is aided by injection of heart muscle cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cell line, or hiPSCs, that overexpress cyclin D2. This research, published in the journal Circulation, used a pig model of heart attacks, which more closely resembles the human heart in size and physiology, and thus has higher clinical relevance to human disease, compared to studies in mice.

An enduring challenge for bioengineering researchers is the failure of the heart to regenerate muscle tissue after a heart attack has killed part of its muscle wall. That dead tissue can strain the surrounding muscle, leading to a lethal heart enlargement.

Heart experts thus have sought to create new tissue -- applying ...

Inspired by nature, researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), along with collaborators from Washington State University, created a novel material capable of capturing light energy. This material provides a highly efficient artificial light-harvesting system with potential applications in photovoltaics and bioimaging.

The research provides a foundation for overcoming the difficult challenges involved in the creation of hierarchical functional organic-inorganic hybrid materials. Nature provides beautiful examples of hierarchically structured hybrid materials such as bones and teeth. These materials typically showcase a precise atomic ...

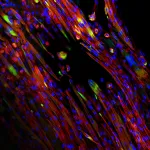

HOUSTON - (May 14, 2021) - Rice University bioengineers are fabricating and testing tunable electrospun scaffolds completely derived from decellularized skeletal muscle to promote the regeneration of injured skeletal muscle.

Their paper in Science Advances shows how natural extracellular matrix can be made to mimic native skeletal muscle and direct the alignment, growth and differentiation of myotubes, one of the building blocks of skeletal muscle. The bioactive scaffolds are made in the lab via electrospinning, a high-throughput process that can produce single micron-scale fibers.

The research could ease the burden of performing an estimated ...

Scientists have used fibre-optic sensing to obtain the most detailed measurements of ice properties ever taken on the Greenland Ice Sheet. Their findings will be used to make more accurate models of the future movement of the world's second-largest ice sheet, as the effects of climate change continue to accelerate.

The research team, led by the University of Cambridge, used a new technique in which laser pulses are transmitted in a fibre-optic cable to obtain highly detailed temperature measurements from the surface of the ice sheet all the way to the base, more than 1000 metres below.

In contrast to previous studies, which measured temperature from separate sensors located tens or even hundreds of metres apart, the new approach allows temperature ...

A microscope used by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek to conduct pioneering research contains a surprisingly ordinary lens, as new research by Rijksmuseum Boerhaave Leiden and TU Delft shows. It is a remarkable finding, because Van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) led other scientists to believe that his instruments were exceptional. Consequently, there has been speculation about his method for making lenses for more than three centuries. The results of this study were published in Science Advances on May 14.

Previous research carried out in 2018 already indicated that some of Van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes contained common ground lenses. Researchers have now examined ...

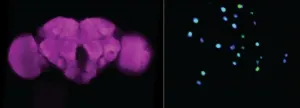

In research made possible when COVID-19 sidelined other research projects, scientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine meticulously counted brain cells in fruit flies and three species of mosquitos, revealing a number that would surprise many people outside the science world.

The insects' tiny brains, on average, have about 200,000 neurons and other cells, they say. By comparison, a human brain has 86 billion neurons, and a rodent brain contains about 12 billion. The figure probably represents a "floor" for the number needed to perform the bugs' complex behaviors.

"Even though these brains are simple [in contrast to mammalian brains], they can do a lot of processing, even more than a supercomputer," says Christopher Potter, Ph.D., associate professor of neuroscience ...

Being treated fairly is important - but fairness alone isn't enough to make people feel valued in a workplace or other groups, new research suggests.

Researchers found that "distinctive treatment" - where a person's talents and qualities are recognised - provides this sense of value while also reinforcing their sense of inclusion. It also promotes mental health.

The findings suggest there is no conflict between "fitting in" and "standing out" in groups - in fact, they complement each other.

But while the importance of fairness is widely accepted, the researchers say distinctive treatment is ...