(Press-News.org) Berkeley – Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, have developed a new technique that allows plasmon lasers to operate at room temperature, overcoming a major barrier to practical utilization of the technology.

The achievement, described Dec. 19 in an advanced online publication of the journal Nature Materials, is a "major step towards applications" for plasmon lasers, said the research team's principal investigator, Xiang Zhang, UC Berkeley professor of mechanical engineering and faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

"Plasmon lasers can make possible single-molecule biodetectors, photonic circuits and high-speed optical communication systems, but for that to become reality, we needed to find a way to operate them at room temperature," said Zhang, who also directs at UC Berkeley the Center for Scalable and Integrated Nanomanufacturing, established through the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Nano-scale Science and Engineering Centers program.

In recent years, scientists have turned to plasmon lasers, which work by coupling electromagnetic waves with the electrons that oscillate at the surface of metals to squeeze light into nanoscale spaces far past its natural diffraction limit of half a wavelength. Last year, Zhang's team reported a plasmon laser that generated visible light in a space only 5 nanometers wide, or about the size of a single protein molecule.

But efforts to exploit such advancements for commercial devices had hit a wall of ice.

"To operate properly, plasmon lasers need to be sealed in a vacuum chamber cooled to cryogenic temperatures as low as 10 kelvins, or minus 441 degrees Fahrenheit, so they have not been usable for practical applications," said Renmin Ma, a post-doctoral researcher in Zhang's lab and co-lead author of the Nature Materials paper.

In previous designs, most of the light produced by the laser leaked out, which required researchers to increase amplification of the remaining light energy to sustain the laser operation. To accomplish this amplification, or gain increase, researchers put the materials into a deep freeze.

To plug the light leak, the scientists took inspiration from a whispering gallery, typically an enclosed oval-shaped room located beneath a dome in which sound waves from one side are reflected back to the other. This reflection allows people on opposite sides of the gallery to talk to each other as if they were standing side by side. (Some notable examples of whispering galleries include the U.S. Capitol's Statuary Hall, New York's Grand Central Terminal, and the rotunda at San Francisco's city hall.)

Instead of bouncing back sound waves, the researchers used a total internal reflection technique to bounce surface plasmons back inside a nano-square device. The configuration was made out of a cadmium sulfide square measuring 45 nanometers thick and 1 micrometer long placed on top of a silver surface and separated by a 5 nanometer gap of magnesium fluoride.

The scientists were able to enhance by 18-fold the emission rate of light, and confine the light to a space of about 20 nanometers, or one-twentieth the size of its wavelength. By controlling the loss of radiation, it was no longer necessary to encase the device in a vacuum cooled with liquid helium. The laser functioned at room temperature.

"The greatly enhanced light matter interaction rates means that very weak signals might be observable," said Ma. "Lasers with a mode size of a single protein are a key milestone toward applications in ultra-compact light source in communications and biomedical diagnostics. The present square plasmon cavities not only can serve as compact light sources, but also can be the key components of other functional building-blocks in integrated circuits, such as add-drop filters, direction couplers and modulators."

INFORMATION:

Rupert Oulton, a former post-doctoral researcher in Zhang's lab and now a lecturer at Imperial College London, is the other co-lead author of the paper. Other co-authors are Volker Sorger, a UC Berkeley Ph.D. student in mechanical engineering, and Guy Bartal, a former research scientist in Zhang's lab.

The U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the NSF helped support this work.

Scientists take plasmon lasers out of deep freeze

2010-12-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Despite damage, membrane protein structure can be seen using new X-ray technology, study reveals

2010-12-21

Australian researchers have identified a way to measure the structure of membrane proteins despite being damaged when using X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs), a discovery that will help fast track the development of targeted drugs using emerging XFELs technology.

About 70% of drugs on the market today depend on the activity of membrane proteins, which are complex molecules that form the membranes of the cells in our body.

A major problem for the design of new pharmaceuticals, often known as the "membrane protein problem", is that they do not form the crystals needed ...

Study identifies cells that give rise to brown fat

2010-12-21

BOSTON – December 20, 2010 – In some adults, the white fat cells that we all stockpile so readily are supplemented by a very different form of fat—brown fat cells, which can offer the neat trick of burning energy rather than storing it. Researchers at Joslin Diabetes Center, which last year led the way in demonstrating an active role for brown fat in adults, now have identified progenitor cells in mouse white fat tissue and skeletal muscle that can be transformed into brown fat cells.

"This finding opens up a whole new avenue for researchers interested in designing molecules ...

Acid suppressive medication may increase risk of pneumonia

2010-12-21

Using acid suppressive medications, such as proton pump inhibitors and histamine2 receptor antagonists, may increase the risk of developing pneumonia, states an article in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) (pre-embargo link only) http://www.cmaj.ca/embargo/cmaj092129.pdf.

Acid suppressive drugs are the second leading medication worldwide, totaling over US$26 billion in sales in 2005. Recently, medical literature has looked at unrecognized side effects in popular medications and their impact on public health.

This systematic review, which incorporated all relevant ...

Strict heart rate control provides no advantage over lenient approach

2010-12-21

Strictly controlling the heart rate of patients with atrial fibrillation provides no advantage over more lenient heart rate control, experts report in a focused update of the 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation.

The new recommendations, published in Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association, the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, and HeartRhythm Journal, are updates of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients ...

Young female chimps treat sticks like dolls

2010-12-21

Researchers have reported some of the first evidence that chimpanzee youngsters in the wild may tend to play differently depending on their sex, just as human children around the world do. Although both young male and female chimpanzees play with sticks, females do so more often, and they occasionally treat them like mother chimpanzees caring for their infants, according to a study in the December 21st issue of Current Biology, a Cell Press publication.

The findings suggest that the consistently greater tendency, across all cultures, for girls to play more with dolls ...

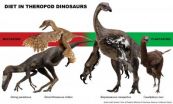

Meat-eating dinosaurs not so carnivorous after all

2010-12-21

December 20th, 2010 – Tyrannosaurus rex may have been a flesh-eating terror but many of his closest relatives were more content with vegetarian fare, a new analysis by Field Museum scientists has found.

The scientists, Lindsay Zanno and Peter Makovicky, who will publish their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used statistical analyses to determine the diet of 90 species of theropod dinosaurs. Their results challenge the conventional view that nearly all theropods hunted prey, especially those closest to the ancestors of birds. ...

Brain imaging predicts future reading progress in children with dyslexia

2010-12-21

NASHVILLE, Tenn.—Brain scans of adolescents with dyslexia can be used to predict the future improvement of their reading skills with an accuracy rate of up to 90 percent, new research indicates. Advanced analyses of the brain activity images are significantly more accurate in driving predictions than standardized reading tests or any other measures of children's behavior.

The finding raises the possibility that a test one day could be developed to predict which individuals with dyslexia would most likely benefit from specific treatments.

The research was published ...

Expansion of HIV screening cost-effective in reducing spread of AIDS, Stanford study shows

2010-12-21

STANFORD, Calif. — An expanded U.S. program of HIV screening and treatment could prevent as many as 212,000 new infections over the next 20 years and prove to be very cost-effective, according to a new study by Stanford University School of Medicine researchers.

The researchers found that screening high-risk people annually and low-risk people once in their lifetimes was a worthwhile and cost-effective approach to help curtail the epidemic. The screening would have to be coupled with treatment of HIV-infected individuals, as well as programs to help change risky behaviors.

"We ...

Neuroimaging at Stanford helps to predict which dyslexics will learn to read

2010-12-21

STANFORD, Calif. — Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have used sophisticated brain imaging to predict with 90 percent accuracy which teenagers with dyslexia would improve their reading skills over time.

Their work, the first to identify specific brain mechanisms involved in a person's ability to overcome reading difficulties, could lead to new interventions to help dyslexics better learn to read.

"This gives us hope that we can identify which children might get better over time," said Fumiko Hoeft, MD, PhD, an imaging expert and instructor at ...

Children with autism lack visual skills required for independence

2010-12-21

The ability to find shoes in the bedroom, apples in a supermarket, or a favourite animal at the zoo is impaired among children with autism, according to new research from the University of Bristol. Contrary to previous studies, which show that children with autism often demonstrate outstanding visual search skills, this new research indicates that children with autism are unable to search effectively for objects in real-life situations – a skill that is essential for achieving independence in adulthood.

Previous studies have tested search skills using table-top tasks ...