(Press-News.org) In the human gut, good bacteria make great neighbors.

A new Northwestern University study found that specific types of gut bacteria can protect other good bacteria from cancer treatments -- mitigating harmful, drug-induced changes to the gut microbiome. By metabolizing chemotherapy drugs, the protective bacteria could temper short- and long-term side effects of treatment.

Eventually, the research could potentially lead to new dietary supplements, probiotics or engineered therapeutics to help boost cancer patients' gut health. Because chemotherapy-related microbiome changes in children are linked to health complications later in life -- including obesity, asthma and diabetes -- discovering new strategies for protecting the gut is particularly important for pediatric cancer patients.

"We were really inspired by bioremediation, which uses microbes to clean up polluted environments," said Northwestern's Erica Hartmann, the study's senior author. "Usually bioremediation applies to groundwater or soil, but, here, we have applied it to the gut. We know that certain bacteria can breakdown toxic cancer treatments. We wondered if, by breaking down drugs, these bacteria could protect the microbes around them. Our study shows the answer is 'yes.' If some bacteria can break down toxins fast enough, that provides a protective effect for the microbial community."

The research will be published on May 26 in the journal mSphere.

Hartmann is an assistant professor of environmental biology at Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering. Ryan Blaustein, a former postdoctoral fellow in Hartmann's laboratory, is the paper's first author. He is now a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health.

Although cancer treatments are life-saving, they also cause profoundly harsh and painful side effects, including gastrointestinal issues. Chemotherapies, in particular, can obliterate the healthy, "good" bacteria in the human gut.

"Chemotherapy drugs do not differentiate between killing cancer cells and killing microbes," Hartmann said. "Microbes in your gut help digest your food and keep you healthy. Killing these microbes is especially harmful for children because there's some evidence that disruption in the gut microbiome early in life can lead to potential health conditions later in life."

Working with Dr. Patrick Seed, a professor of pediatrics and microbiology-immunology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Hartmann's lab learned from Raoultella planticola. Naturally occurring in the human gut in low abundances, Raoultella planticola can break down chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, which has been demonstrated in other research.

To test whether or not this breakdown effect could protect the entire microbiome, the team developed simplified microbial communities, which included various types of bacteria typically found in the human gut. The "mock gut communities" included bacteria strains (Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae) that are good at breaking down doxorubicin, strains (Clostridium innocuum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus) that are especially sensitive to doxorubicin and one strain (Enterococcus faecium) that is resistant to doxorubicin but does not break it down.

The team then exposed these mock gut communities" to doxorubicin and found increased survival among sensitive strains. The researchers concluded that, by degrading doxorubicin, certain bacteria made the drugs less toxic to the rest of the gut.

Although the research highlights a promising new pathway for potentially protecting cancer patients, Hartmann cautions that translating the new findings into treatments is still far off.

"There are several eventual applications that would be great to help cancer patients -- particularly pediatric patients -- not experience such harsh side effects," she said. "But we're still far from actually making that a reality."

INFORMATION:

MOSCOW, Idaho -- May 26, 2021 -- University of Idaho researchers partnered with other scientists from the United States and Australia to study the evolution of Tasmanian devils in response to a unique transmissible cancer.

The team found that historic and ongoing evolution are widespread across the devils' genome, but there is little overlap of genes between those two timescales. These findings, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggest that if transmissible cancers occurred historically in devils, they imposed natural selection on different sets of genes.

Tasmanian devils suffer from a transmissible cancer called devil facial tumor disease (DFTD). Unlike typical cancers, tumor cells from transmissible cancers are directly transferred from one individual ...

Children of Latinx immigrants who take on adult responsibilities exhibit higher levels of political activity compared with those who do not, according to University of Georgia researcher Roberto Carlos.

Immigrant communities often display low levels of political engagement, but a new study by Carlos indicates that when children of Latinx immigrants take on adult roles because of parents' long work hours, immigrant status or language deficiencies, they develop noncognitive skills associated with higher rates of political participation.

"There is thriving in spaces that we wouldn't necessarily expect because of the hardship related ...

"If you can't measure it, you can't improve it". This concept is also true within the context of climate policy, where the achievement of the objectives of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is dependent on the ability of the international community to accurately measure greenhouse gas (GHG) emission trends and, consequently, to alter these trends.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emission inventories represent the link between national and international political actions on climate change, and climate and environmental sciences. Research communities and inventory agencies have approached the problem of climate ...

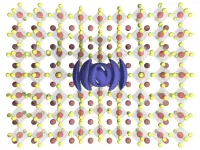

Researchers at McGill University have gained new insight into the workings of perovskites, a semiconductor material that shows great promise for making high-efficiency, low-cost solar cells and a range of other optical and electronic devices.

Perovskites have drawn attention over the past decade because of their ability to act as semiconductors even when there are defects in the material's crystal structure. This makes perovskites special because getting most other semiconductors to work well requires stringent and costly manufacturing techniques to produce crystals that are as defect-free ...

SAN FRANCISCO, CA--May 26, 2021--In January 2021, reports of a new coronavirus variant that had emerged in California raised many concerns. Preliminary data suggested that it is more transmissible than the unmutated strains of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) from which it evolved.

Now, a multifaceted collaboration between researchers at UC San Francisco, Gladstone Institutes, and other organizations across California provides a comprehensive portrait of the variant--including its interaction with the immune system and its potential to spread.

"Our ...

Even though people stayed in touch during the pandemic's stay-at-home orders and social distancing, it was easy to feel out of touch with loved ones.

Technology and the internet have expanded the way humans communicate and added much to that communication -- think emojis, GIFs and memes. But they can still fall short of being physically with someone.

"Our social cues are limited online," said Fannie Liu, a research scientist at Snap Inc who earned her Ph.D. from the Human-Computer Interaction Institute in Carnegie Mellon University's School of Computer Science. "We're exploring a new way to support digital connection through a deeper and more internal cue."

Liu was part of a team from CMU, Snap and the University ...

A new study looking across a large body of research finds further evidence for the safety of vaccines that are Food and Drug Administration-approved and routinely recommended for children, adults and pregnant women. The study updates a vaccine safety review that was released by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in 2014.

"This in-depth analysis found no evidence of increased risk of serious adverse events following vaccines, apart from a few - previously known - associations," said Susanne Hempel, director of the Southern California Evidence Review Center.

The meta-analysis, ...

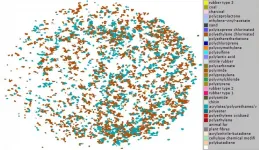

In cities, heavy rains wash away the gunk collecting on sidewalks and roads, picking up all kinds of debris. However, the amount of microplastic pollution swept away by this runoff is currently unknown. Now, researchers in ACS ES&T Water report that stormwater can be a large source of microplastics and rubber fragments to water bodies and, with a proof-of-concept experiment, show that a rain garden could keep these microscopic pieces out of a storm drain.

Most cities' storm drains end up discharging directly into wetlands, creeks or rivers. Rainwater running into these drains becomes a concoction of whatever is on the ground, including dirt and grass clippings, leaked car fluids, fertilizer and garbage. Recently, researchers also found that ...

Scientists have got up close and personal with human sewage to determine how best to measure hidden and potentially dangerous plastics.

As the way microplastics are measured and counted varies from place to place, there is no agreed understanding of the weight of the problem. Until scientists can agree on one way of measuring them, life on land and sea will continue to ingest who knows how much plastic, affecting health for generations.

A new study, published today in Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, by the University of Portsmouth has examined one method, using a chemical solution called 'Fenton reagent' to ...

WHAT:

The immune system's attempt to eliminate Salmonella bacteria from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract instead facilitates colonization of the intestinal tract and fecal shedding, according to National Institutes of Health scientists. The study, published in Cell Host & Microbe, was conducted by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) scientists at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana.

Salmonella Typhimurium bacteria (hereafter Salmonella) live in the gut and often cause gastroenteritis in people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates Salmonella bacteria cause about ...