(Press-News.org) In 2015, nearly half of Hawai?i's coral reefs were affected by the most severe bleaching event to date. Coral bleaching occurs when warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures prompt corals to expel the algae that normally live inside them and on which the corals rely for food.

Bleaching events are dismaying, but corals can sometimes recover, while others resist bleaching altogether. In a new study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers led by Katie Barott of the University of Pennsylvania found that these battle-tested, resilient corals could thrive, even when transplanted to a different environment and subjected to additional heat stress. The findings offer hope that hardy corals could serve as a founding population to restore reefs in the future.

"The big thing that we were really interested in here was trying to experimentally test whether you an take a coral that seems to be resistant to climate chage and use that as the seed stock to propagate and put out on a different reef that might be degraded," Barott says. "The cool thing was we didn't see any differences in their bleaching response after this transplant."

Mass coral bleaching events are getting increasingly frequent, raising worries that corals will become victims of climate change in the near future. Yet Barott and colleagues have been studying the corals that resist bleaching, with an eye toward buying corals more time to hang on in the face of warming and acidifying ocean waters.

One strategy they and others have envisioned, and which has been trialed in areas such as the Great Barrier Reef, is coral transplantation. Researchers could replenish reefs damaged by climate change--or other anthropogenic insults, such as sedimentation or a ship grounding--with corals that had proved sturdy and able to survive in the face of tough conditions.

For this to work, however, would require the coral "survivors" to continue to display their resilient characteristics after being moved to a new environment.

"If you take a coral that is resistant to bleaching in its native habitat, it could be that the stress of moving to a new place might make them lose that ability," Barott says.

Just as a fern that grew well in the shade might wilt if moved to a sunny plot, the conditions of a new environment, including water flow rate, food access, light, and nutrient availability, could could affect the resilience of transplanted corals.

Barott and colleagues went after this question with an experiment in two reefs in Hawai?i's Ka?ne?ohe Bay on the island of O?ahu: one closer to shore with more stagnant waters and another farther from shore with higher flow. In each area, the researchers identified coral colonies that had resisted bleaching during the 2015 bleaching event and collected samples from them the following year. Corals are clonal organisms, and so a chunk taken from a colony can regrow and will have the same genetics as the "mother" coral. For each colony, they kept some samples on their native reef and transplanted others to the second reef.

After the corals had spent six months at their new location, the biologists also put coral samples from each site in tanks in the lab and simulated another bleaching event by raising the water temperature over a period of several days.

Carefully tracking the corals' health and the conditions of the surrounding environment, the team measured photosynthesis rates, metabolism, and calcification rates, as well as the health of the symbiotic algae. They found that bleaching-resistant corals stayed that way, even in a new environment.

"What was really novel is that we had this highly replicated experiment," Barott says, "and we saw no change in the coral's bleaching response."

The researchers also looked at how well the corals reproduced the summer that followed their collection. A coral's native site conditions had an impact on their future reproductive fitness, they discovered.

"The corals from the 'happy' site--the outer lagoon that had higher growth rates prior to the bleaching event--generally seemed a little happier and their fitness was higher," Barott says. "That tells us that, if you're going to have a coral nursery, you should pick a site with good conditions because there seems to be some carryover benefit of spending time at a nicer site even after the corals are outplanted to a less 'happy' site."

The "happy" site, the lagoon farther from shore, had higher flow rates than the other reef, which is closer to shore, less salty, and more stagnant. "Higher flow rates are really important for helping corals get rid of waste and get food," Barott says.

Barott, who started the work as a postdoc at the Hawai?i Institute of Marine Biology, is continuing to pursue research on coral resiliency in her lab at Penn, including an investigation of the effects of heat stress and bleaching on reproductive success and the function of coral sperm.

While the results of the transplantation study are promising, she says that it would only be a temporary solution to the threat of climate change.

"I think techniques like this can buy us a little bit of time, but there isn't a substitute for capping carbon emissions," she says. "We need global action on climate change because even bleaching-resistant corals aren't going to survive forever if ocean warming keeps increasing as fast as it is today."

INFORMATION:

Katie L. Barott is an assistant professor in the Department of Biology in the University of Pennsylvania School of Arts & Sciences.

Barott's coauthors on the work were Penn's Teegan Innis and the University of Hawai?i's Ariana S. Huffmyer, Jennifer M. Davidson, Elizabeth Lenz, Shayle B. Matsuda, Joshua R. Hancock, Crawford Drury, Hollie M. Putnam, and Ruth D. Gates.

The study was supported by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, the University of Pennsylvania, and the National Science Foundation (grants 1923743 and 1323822).

Boulder, Colo., USA: The Geological Society of America regularly publishes

articles online ahead of print. For April, GSA Bulletin topics

include multiple articles about the dynamics of China and Tibet; new

insights into the Chicxulub impact structure; and the dynamic topography of

the Cordilleran foreland basin. You can find these articles at

https://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent

.

Tectonic and eustatic control of Mesaverde Group

(Campanian-Maastrichtian) architecture, Wyoming-Utah-Colorado region,

USA

Keith P. Minor; Ronald J. Steel; Cornel Olariu

Abstract:

We describe and analyze the depositional history and stratigraphic

architecture of the Campanian and Maastrichtian ...

WACO, Texas (May 28, 2021) - About 36 million people have blindness including 1 million children. Additionally, 216 million people experience moderate to severe visual impairment. However, STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education maintains a reliance on three-dimensional imagery for education. Most of this imagery is inaccessible to students with blindness. A breakthrough study by Bryan Shaw, Ph.D., professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Baylor University, aims to make science more accessible to people who are blind or visually impaired through small, candy-like models.

The ...

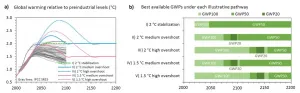

Five researchers shed new light on a key argument to reduce greenhouse gases (GHG): they provided the first economic analysis of conversion factors of other GHG like methane into their CO2 equivalent in overshoot scenarios. Although the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) considers settling for one value of reference (known as "Common Metric") to make this conversion among the Paris Agreement, the models presented here show the economic advantage of flexibility between various factors of conversion. "A key notion in the UNFCCC is to reduce GHG emissions in the least costly way so as to ensure global benefits" highlights Katsumasa Tanaka, primary author of the Science Advances study.

The research provides series of dynamic variations of ...

A study coordinated by Luís Graça, principal investigator at the Instituto de Medicina Molecular João Lobo Antunes (iMM; Portugal) and Professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon (FMUL) used lymph nodes, tonsils and blood, to show how the cells that control production of antibodies are formed and act. The results published now in the scientific journal Science Immunology* unveiled key aspects about the regulation of antibody production, with significant importance for diseases where antibody production is dysregulated such as autoimmune diseases or allergies.

In the last few ...

A new study of dozens of wild fish species commonly consumed in the Peruvian Amazon says that people there could suffer major nutritional shortages if ongoing losses in fish biodiversity continue. Furthermore, the increasing use of aquaculture and other substitutes may not compensate. The research has implications far beyond the Amazon, since the diversity and abundance of wild-harvested foods is declining in rivers and lakes globally, as well as on land. Some 2 billion people globally depend on non-cultivated foods; inland fisheries alone employ some 60 million people, and provide the primary source of protein for some 200 million. The study appears this week in the journal Science Advances.

The ...

Centuries-old smoke particles preserved in the ice reveal a fiery past in the Southern Hemisphere and shed new light on the future impacts of global climate change, according to new research published in Science Advances.

"Up till now, the magnitude of past fire activity, and thus the amount of smoke in the preindustrial atmosphere, has not been well characterized," said Pengfei Liu, a former graduate student and postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and first author of the paper. "These results have importance for understanding the evolution of climate change from the 1750s until ...

Since the onset of the CRISPR genetic editing revolution, scientists have been working to leverage the technology in the development of gene drives that target pathogen-spreading mosquitoes such as Anopheles and Aedes species, which spread malaria, dengue and other life-threatening diseases.

Much less genetic engineering has been devoted to Culex genus mosquitoes, which spread devastating afflictions stemming from West Nile virus--the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the continental United States--as well as other viruses such as the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and the pathogen causing avian malaria, a threat to ...

DALLAS - May 28, 2021 - A study of gene activity in the brain's hippocampus, led by UT Southwestern researchers, has identified marked differences between the region's anterior and posterior portions. The END ...

East Hanover, NJ. May 28, 2021. A team of researchers has shown that physical intervention plans that included exoskeleton-assisted walking helped people with spinal cord injury evacuate more efficiently and improved the consistency of their stool. This finding was reported in Journal of Clinical Medicine on March 2, 2021, in the article "The Effect of Exoskeletal-Assisted Walking on Spinal Cord Injury Bowel Function: Results from a Randomized Trial and Comparison to Other Physical Interventions" (doi: 10.3390/jcm10050964).

The authors are Peter H. Gorman, MD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Gail F. Forrest, PhD, of Kessler Foundation's Tim and Caroline Reynolds Center for Spinal Stimulation, Dr. William Scott, of VA Maryland Healthcare System, ...

Neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease and epilepsy have had some treatment success with deep brain stimulation, but those require surgical device implantation. A multidisciplinary team at Washington University in St. Louis has developed a new brain stimulation technique using focused ultrasound that is able to turn specific types of neurons in the brain on and off and precisely control motor activity without surgical device implantation.

The team, led by Hong Chen, assistant professor of biomedical engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering and of radiation oncology at the School of Medicine, is the first to provide direct evidence showing noninvasive, cell-type-specific ...