(Press-News.org) A team of students working with Jonathan Boreyko, associate professor in mechanical engineering at Virginia Tech, has discovered the method ducks use to suspend water in their feathers while diving, allowing them to shake it out when surfacing. The discovery opens the door for applications in marine technology. Findings were published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Boreyko has a well-established body of work in the area of fluid mechanics, including the invention of a fog harp and the use of contained, recirculated steam as a cooling device. As his research has progressed throughout the past decade, the mechanics of duck de-wetting has been one of his longest-running projects.

"I got this idea when I was at Duke University," said Boreyko. "I had a really bad parking spot, but my walk took me right through the scenic Duke Gardens. I passed by ponds with lots of ducks, and I noticed that when a duck comes out of the water, they'd shake their feathers and water would fly off. I realized that what they were doing was a de-wetting transition, releasing water that was partially inside of their feathers. That was the germ of the idea. In my research, purely by coincidence, I was studying the same kind of thing. I realized that these transitions work only if the water isn't allowed to get all the way to the bottom of the porous feather structure."

Boreyko remained intrigued with how the balance was struck, curious about the mechanisms that allow a duck to hold water in its feathers without sinking completely. He brought Farzad Ahmadi into his lab in 2014 as a graduate student, sharing that intrigue in one of their early meetings. Ahmadi picked up the project and dove into the finer details. Their first approach was simple - they attempted to force a single drop of water through a natural duck feather.

"It didn't work," said Ahmadi. "Then we had the idea to build a pressure chamber to force a pool of water through several layers of feathers."

Under pressure

The team first needed to ensure the water could only penetrate directly through the feathers, as opposed to simply leaking around their outer edges. To achieve this, they sealed one feather at a time, leaving only a small area exposed. The researchers sealed each layer, leaving an area exposed in the same place on each surface. This allowed them to create a column of exposed feather surfaces upward through the stack. A thin pool of water was poured over the top exposed surface. The stack was placed in a pressure chamber, and gas pressure was employed to push the water downward through the feathers. A camera was placed at the bottom to observe the water as it passed through the layers.

Feathers have micro-sized openings in them, tiny slots that allow pressurized water to pass through. A duck sitting on the surface of a pond isn't encountering any water pressure, so the water penetration is negligible. A duck diving downward, however, encounters a steady increase in hydrostatic pressure, something familiar to anyone taking a dive into the deep end of a pool.

Ahmadi discovered that as the number of feather layers increases, the pressure required to push water through all the layers must also increase. This establishes a kind of baseline, a maximum pressure up to which feathers hold the water entering them, but do not allow the water to reach a duck's skin.

"Our hypothesis was to use multiple layers of feathers so that the water only comes in part way, but there are air pockets under that," Boreyko explained. "As long as those air pockets are present, it prevents something called irreversible wetting. As long as the wetting is only partial, they can shake it out when they surface."

Ahmadi also discovered that species of ducks tend to have the exact number of feather layers needed to avoid irreversible wetting during their dives. A mallard, for instance, has four layers of feathers. The maximum depth to which a typical mallard dives corresponds to a hydrostatic pressure that invaded a three-feather stack but not four. In this way, at least one layer of feathers remains dry after a dive, allowing the duck to shake out the water when it emerges.

Designing synthetic feathers

Having established the foundational mechanics of duck de-wetting, Boreyko's team set out to create a synthetic material that works in a similar way. The team made bio-inspired feathers from a thin sheet of aluminum foil, laser cutting an array of slots one-tenth of a millimeter wide to mimic the barbules of a duck feather. They also re-created the hairy nanostructure of feathers by adding an aluminum nanostructure to the aluminum barbules.

The synthetic feathers produced nearly identical results during testing, a credit to the strength of nature's design. Application and scaling of this technology is a logical next step for Boreyko, and he has a few ideas.

This layer effect may be helpful for trapping air pockets in desalination membranes, mechanisms that remove salt from seawater. Boreyko also thinks there is potential for applying layered synthetic feathers to the exterior of a boat, to make the boat travel more easily through the water and reduce the amount of barnacle-like organisms that cling to the hull.

"If we think of a ship moving over the water as an engineered bird, right now it's swimming naked," Boreyko says. "We wonder if clothing the ship in feathers could impart the same enhancements that waterfowl benefit from."

INFORMATION:

Jack Tseng loves bone-crunching animals -- hyenas are his favorite -- so when paleontologist Joseph Peterson discovered fossilized dinosaur bones that had teeth marks from a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex, Tseng decided to try to replicate the bite marks and measure how hard those kids could actually chomp down.

Last year, he and Peterson made a metal replica of a scimitar-shaped tooth of a 13-year-old juvie T. rex, mounted it on a mechanical testing frame commonly used in engineering and materials science, and tried to crack a cow legbone with it.

Based on 17 successful attempts to match the depth and shape of the bite marks on the fossils -- he had to toss out some trials because the fresh bone slid around too much -- he determined that a juvenile could have exerted ...

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. -- Scientists at Sandia National Laboratories have built the world's smallest and best acoustic amplifier. And they did it using a concept that was all but abandoned for almost 50 years.

According to a paper published May 13 in Nature Communications, the device is more than 10 times more effective than the earlier versions. The design and future research directions hold promise for smaller wireless technology.

Modern cell phones are packed with radios to send and receive phone calls, text messages and high-speed data. The more radios in a device, the more it can do. While most radio components, including amplifiers, are electronic, they can potentially ...

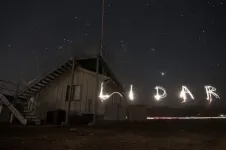

Twice a day, at dusk and just before dawn, a faint layer of sodium and other metals begins sinking down through the atmosphere, about 90 miles high above the city of Boulder, Colorado. The movement was captured by one of the world's most sensitive "lidar" instruments and reported today in the AGU journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The metals in those layers come originally from rocky material blasting into Earth's atmosphere from space, and the regularly appearing layers promise to help researchers understand better how earth's atmosphere interacts with space, even potentially how those interactions help support life.

"This is an important discovery because we have never seen these dusk/dawn features before, and because these metal layers affect many things. The ...

DALLAS, June 2, 2021 -- A "prescription" to sit less and move more is the optimal first treatment choice for reducing mild to moderately elevated blood pressure and blood cholesterol in otherwise healthy adults, according to the new American Heart Association scientific statement published today in the American Heart Association's journal Hypertension.

"The current American Heart Association guidelines for diagnosing high blood pressure and cholesterol recognize that otherwise healthy individuals with mildly or moderately elevated levels of these ...

A large group of iconic fossils widely believed to shed light on the origins of many of Earth's animals and the communities they lived in may be hiding a secret.

Scientists, led by two from the University of Portsmouth, UK, are the first to model how exceptionally well preserved fossils that record the largest and most intense burst of evolution ever seen could have been moved by mudflows.

The finding, published in Communications Earth & Environment, offers a cautionary note on how palaeontologists build a picture from the remains of the creatures they study.

Until now, it has been widely accepted the fossils buried in mudflows in the Burgess Shale in Canada that show the result of the Cambrian ...

CRISPR-based technologies offer enormous potential to benefit human health and safety, from disease eradication to fortified food supplies. As one example, CRISPR-based gene drives, which are engineered to spread specific traits through targeted populations, are being developed to stop the transmission of devastating diseases such as malaria and dengue fever.

But many scientists and ethicists have raised concerns over the unchecked spread of gene drives. Once deployed in the wild, how can scientists prevent gene drives from uncontrollably spreading across populations ...

CHICAGO -- Women who experience acute aortic dissection--a spontaneous and catastrophic tear in one of the body's main arteries--not only are older and have more advanced disease than men when they seek medical care, but they also are more likely to die, according to research published online today in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.

"Data over the course of the last few decades demonstrate differences in both presentation and outcomes between males and females who have acute aortic dissection, with greater mortality among females," said Thomas G. Gleason, MD, from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. "This study underscores ...

Can you trust the map on your smartphone, or the satellite image on your computer screen?

So far, yes, but it may only be a matter of time until the growing problem of "deep fakes" converges with geographical information science (GIS). Researchers such as Associate Professor of Geography Chengbin Deng are doing what they can to get ahead of the problem.

Deng and four colleagues -- Bo Zhao and Yifan Sun at the University of Washington, and Shaozeng Zhang and Chunxue Xu at Oregon State University -- co-authored a recent article in Cartography and Geographic Information Science that explores the problem. In "Deep ...

Popcorn. What would movies and sporting events without this salty, buttery snack? America's love for this snack goes beyond these events. We consume 15 billion quarts of popped popcorn each year.

When it comes to popcorn, consumers want a seed-to-snack treat that leaves more snacks than seeds when popped. This means when they pop the corn, there shouldn't be many unpopped kernels left in the bowl.

Maria Fernanda Maioli set out to determine the properties affecting popping expansion in popcorn. The team's research was recently published in Agronomy Journal, a publication of the American Society of Agronomy.

"The way kernels expand is a basic, ...

BEER-SHEVA, Israel...June 2, 2021 - As drones become more ubiquitous in public spaces, researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) have conducted the first studies examining how people respond to various emotional facial expressions depicted on a drone, with the goal of fostering greater social acceptance of these flying robots.

The research, which was presented recently at the virtual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, reveals how people react to common facial expressions superimposed on drones.

"There is a lack of research on how drones are perceived and understood by humans, which is vastly different than ground robots." says Prof. Jessica Cauchard together with Viviane Herdel of BGU's Magic Lab, in the BGU Department of Industrial ...