(Press-News.org) BAR HARBOR, MAINE — Many salamanders can readily regenerate a lost limb, but adult mammals, including humans, cannot. Why this is the case is a scientific mystery that has fascinated observers of the natural world for thousands of years.

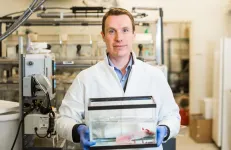

Now, a team of scientists led by James Godwin, Ph.D., of the MDI Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, has come a step closer to unraveling that mystery with the discovery of differences in molecular signaling that promote regeneration in the axolotl, a highly regenerative salamander, while blocking it in the adult mouse, which is a mammal with limited regenerative ability.

"Scientists at the MDI Biological Laboratory have been relying on comparative biology to gain insights into human health since its founding in 1898," said Hermann Haller, M.D., the institution's president. "The discoveries enabled by James Godwin's comparative studies in the axolotl and mouse are proof that the idea of learning from nature is as valid today as it was more than one hundred and twenty years ago."

Instead of regenerating lost or injured body parts, mammals typically form a scar at the site of an injury. Because the scar creates a physical barrier to regeneration, research in regenerative medicine at the MDI Biological Laboratory has focused on understanding why the axolotl doesn't form a scar - or, why it doesn't respond to injury in the same way that the mouse and other mammals do.

"Our research shows that humans have untapped potential for regeneration," Godwin said. "If we can solve the problem of scar formation, we may be able to unlock our latent regenerative potential. Axolotls don't scar, which is what allows regeneration to take place. But once a scar has formed, it's game over in terms of regeneration. If we could prevent scarring in humans, we could enhance quality of life for so many people."

The axolotl as a model for regeneration

The axolotl, a Mexican salamander that is now all but extinct in the wild, is a favorite model in regenerative medicine research because of its one-of-a-kind status as nature's champion of regeneration. While most salamanders have some regenerative capacity, the axolotl can regenerate almost any body part, including brain, heart, jaws, limbs, lungs, ovaries, spinal cord, skin, tail and more.

Since mammalian embryos and juveniles have the ability to regenerate - for instance, human infants can regenerate heart tissue and children can regenerate fingertips - it's likely that adult mammals retain the genetic code for regeneration, raising the prospect that pharmaceutical therapies could be developed to encourage humans to regenerate tissues and organs lost to disease or injury instead of forming a scar.

In his recent research, Godwin compared immune cells called macrophages in the axolotl to those in the mouse with the goal of identifying the quality in axolotl macrophages that promotes regeneration. The research builds on earlier studies in which Godwin found that macrophages are critical to regeneration: when they are depleted, the axolotl forms a scar instead of regenerating, just like mammals.

The recent research found that although macrophage signaling in the axolotl and in the mouse were similar when the organisms were exposed to pathogens such as bacteria, funguses and viruses, when it came to exposure to injury it was a different story: the macrophage signaling in the axolotl promoted the growth of new tissue while that in the mouse promoted scarring.

The paper on the research, entitled "Distinct TLR Signaling in the Salamander Response to Tissue Damage" was recently published in the journal Developmental Dynamics. In addition to Godwin, authors include Nadia Rosenthal, Ph.D., of The Jackson Laboratory; Ryan Dubuque and Katya E. Chan of the Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute (ARMI); and Sergej Nowoshilow, Ph.D., of the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna, Austria.

Godwin, who holds a joint appointment with The Jackson Laboratory, was formerly associated with ARMI and Rosenthal is ARMI's founding director. The MDI Biological Laboratory and ARMI have a partnership agreement to promote research and education on regeneration and the development of new therapies to improve human health.

Specifically, the paper reported that the signaling response of a class of proteins called toll-like receptors (TLRs), which allow macrophages to recognize a threat such an infection or a tissue injury and induce a pro-inflammatory response, were "unexpectedly divergent" in response to injury in the axolotl and the mouse. The finding offers an intriguing window into the mechanisms governing regeneration in the axolotl.

Being able to 'pull the levers of regeneration'

The discovery of an alternative signaling pathway that is compatible with regeneration could ultimately lead to regenerative medicine therapies for humans. Though regrowing a human limb may not be realistic in the short term, significant opportunities exist for therapies that improve clinical outcomes in diseases in which scarring plays a major role in the pathology, including heart, kidney, liver and lung disease.

"We are getting closer to understanding how axolotl macrophages are primed for regeneration, which will bring us closer to being able to pull the levers of regeneration in humans," Godwin said. "For instance, I envision being able to use a topical hydrogel at the site of a wound that is laced with a modulator that changes the behavior of human macrophages to be more like those of the axolotl."

Godwin, who is an immunologist, chose to examine the function of the immune system in regeneration because of its role in preparing the wound for repairs as the equivalent of a first responder at the site of an injury. His recent research opens the door to further mapping of critical nodes in TLR signaling pathways that regulate the unique immune environment enabling axolotl regeneration and scar-free repair.

INFORMATION:

Godwin's research is supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant numbers P20GM103423 and P20GM104318 to the MDI Biological Laboratory. ARMI is supported by grants from the State Government of Victoria, Australia. The mouse studies were supported by Jackson Laboratory institutional funds.

About the MDI Biological Laboratory

We aim to improve human health and healthspan by uncovering basic mechanisms of tissue repair, aging and regeneration, translating our discoveries for the benefit of society and developing the next generation of scientific leaders. For more information, please visit mdibl.org.

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University's Computational Biology Department in the School of Computer Science have developed a new process that could reinvigorate the search for natural product drugs to treat cancers, viral infections and other ailments.

The machine learning algorithms developed by the Metabolomics and Metagenomics Lab match the signals of a microbe's metabolites with its genomic signals and identify which likely correspond to a natural product. Knowing that, researchers are better equipped to isolate the natural product to begin developing it for a possible drug.

"Natural products are still one of the most successful paths for drug discovery," said Bahar Behsaz, a project scientist in the lab and lead author of a paper about the process. "And ...

A team of Colorado State University scientists, led by veterinary postdoctoral fellow Dr. Anna Fagre, has detected Zika virus RNA in free-ranging African bats. RNA, or ribonucleic acid, is a molecule that plays a central role in the function of genes.

According to Fagre, the new research is a first-ever in science. It also marks the first time scientists have published a study on the detection of Zika virus RNA in any free-ranging bat.

The findings have ecological implications and raise questions about how bats are exposed to Zika virus in nature. The study was recently published in Scientific Reports, a journal published by Nature Research.

Fagre, a researcher at CSU's Center for Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - All fish are not created equal, at least when it comes to nutritional benefits.

This truth has important implications for how declining fish biodiversity can affect human nutrition, according to a computer modeling study led by Cornell and Columbia University researchers.

The study, "Declining Diversity of Wild-Caught Species Puts Dietary Nutrient Supplies at Risk," published May 28 in Science Advances, focused on the Loreto region of the Peruvian Amazon, where inland fisheries provide a critical source of nutrition for the 800,000 inhabitants.

At the same time, the findings apply to fish biodiversity worldwide, as more than 2 billion people depend on fish as their primary source of animal-derived nutrients.

"Investing in safeguarding biodiversity can deliver ...

Researchers at Kyoto University's Institute for Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS) have developed a new approach to speed up hydrogen atoms moving through a crystal lattice structure at lower temperatures. They reported their findings in the journal Science Advances.

"Improving hydrogen transport in solids could lead to more sustainable sources of energy," says Hiroshi Kageyama of iCeMS who led the study.

Negatively charged hydrogen 'anions' can move very quickly through a solid 'hydride' material, which consists of hydrogen atoms attached to other chemical elements. This system is a promising contender for clean energy, but the fast ...

Stone tools have been made by humans and their ancestors for millions of years. For archaeologists these rocky remnants - lithic artefacts and flakes - are of key importance. Because of their high preservation potential they are among the most common findings in archaeological excavations. Worldwide, numerical dating of these lithic artefacts, especially when they occur as surface findings, remains a major challenge. Usually, stone tools cannot be dated directly, but only when they are embedded in sediment layers together with, for example, organic material. The age of such organic material can be constrained via the radiocarbon technique. If such datable organic remains are ...

Tested on human blood in the lab, the selective nanocapsules could reduce the side effects of a major blood clot dissolving drug, which include bleeding on the brain. If confirmed with animal tests, the nanocapsules could also make the drug more effective at lower doses.

Blood clots, also known as thrombi, are a key cause of strokes and heart attacks which are leading causes of death and ill-health worldwide. They can be treated with a clot dissolving drug called tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) which disrupts clots to clear the blocked blood vessel and re-establish blood ...

Known as nature's own sonar system, echolocation occurs when an animal emits a sound that bounces off objects in the environment, returning echoes that provide information about the surrounding space.

While echolocation is well known in whale or bat species, previous research has also indicated that some blind people may use click-based echolocation to judge spaces and improve their navigation skills.

Equipped with this knowledge, a team of researchers, led by Dr Lore Thaler, of Durham University, UK, delved into the factors that determine how people learn this skill.

Over the course of a 10-week training programme, the team investigated how blindness and age affect learning ...

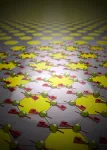

Atomically thin van der Waals magnets are widely seen as the ultimately compact media for future magnetic data storage and fast data processing. Controlling the magnetic state of these materials in real-time, however, has proven difficult. But now, an international team of researchers led by Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) has managed to use light in order to change the anisotropy of a van der Waals antiferromagnet on demand, paving the way to new, extremely efficient means of data storage.

The thin atomic layers that make up van der Waals magnets may seem extremely fragile, but they can be about 200 times stronger ...

In a six-month study of more than 1,000 Americans, R. Kelly Garrett and Robert Bond found that U.S. conservatives were less able to distinguish truth from falsehoods in 20 viral political news stories that appeared online between January and July 2019. Differences in the political orientation of these stories may help explain this observation, the researchers note, writing that "we find that high-profile true political claims tend to promote issues and candidates favored by liberals, while falsehoods tend to be better for conservatives." Two-thirds (65%) of the high-profile true stories were characterized as benefiting the political left, compared with only 10% that were described as benefiting the political right. Among high-profile false stories, 45.8% were perceived to benefit the ...

Individuals at higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer could be identified earlier using machine learning (ML) techniques which would result in a greater number of patients surviving the disease, suggests a new study published in PLOS ONE.

The study was led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and funded by the UK charity Pancreatic Cancer Research Fund (PCRF).

It used UK electronic health records for more than 1,000 patients aged 15-99 years who were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer between January 2005 and June 2009.

The researchers examined numerous symptoms and ...