(Press-News.org) Fruits, vegetables, red wine and chocolate are all rich in polyphenols, natural plant compounds that double as cancer-fighting antioxidants. We can access these foods' health benefits because the microbes in our guts happily feast on them, breaking them down into smaller chemical components.

Microbiome scientists at Colorado State University wanted to know if microbes can also break down those same polyphenols in systems outside the human body, including the microbial wild west of soils.

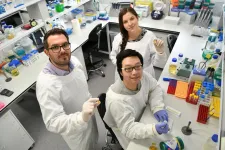

A research team led by Kelly Wrighton, associate professor in the College of Agricultural Sciences' Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, has uncovered new insights into the role of polyphenols in the soil microbiome, known as a black box for its complexity. They proffer an updated theory that soils - much like the human gut - can be food sources for the microbes that live there. Their results could upend a long-held theory that, under certain conditions, soil microbes can't access polyphenols and could thus be used as carbon traps to reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

"Our study opens the door for further study of polyphenol metabolism in the field, and how it fits into natural carbon cycles," said soil and crop sciences Ph.D. candidate Bridget McGivern, first author on the paper describing the work.

Published in Nature Communications, the research involved precisely monitored soil samples subjected to a palette of very high-resolution analytical chemistry in the lab. The researchers set out to prove the concept that microbes in soil, under oxygen-free conditions, do in fact break down polyphenols, likely releasing carbon dioxide.

These experiments fly in the face of the longstanding "enzyme latch" theory that soil microbes do not metabolize polyphenols when oxygen isn't freely available in places like flooded wetlands and peatlands. If it were true that polyphenols remained undigested in oxygen-free soils, it would mean loading up soils with these fibrous compounds could be an easy carbon-trapping sink.

"We know that polyphenols are really sticky, and so people thought that, by being in the soil, not only they themselves wouldn't be broken down, but they'd stick to other carbons and enzymes in the soil and prevent further breakdown of everything else," McGivern said. "So, if you had an already broken-down system like a degraded wetland, you could go in and add wood chips to the system, flood it again, and lock up all the carbon."

Thinking about soil

Wrighton first started thinking about how polyphenols behave in soil systems while a faculty member at Ohio State University; she joined the CSU faculty in 2018.

She couldn't shake the fact that this enzyme latch theory in soils just didn't make sense, based on what we know about how polyphenols are broken down in our guts, which are also oxygen-free environments. Wrighton at that point had become an expert in the gut microbiomes of moose, ruminants which have evolved over millions of years to take full advantage of the polyphenolic compounds in their herbivorous diets.

"The breakdown of polyphenols has to happen in the gut for us to access those antioxidants, and to appreciate chocolate and red wine and all their benefits," said Wrighton, who received a National Science Foundation CAREER award several years ago to study polyphenols. "But then we would go into this other ecosystem, which had a totally different paradigm of how these compounds behaved. We couldn't rationalize that."

Of course, it could be that the inherent complexity of the soil environment provided some other reason for polyphenols to behave differently there, Wrighton surmised. With her hypothesis in hand, and the right high-resolution chemistry tools available, she and McGivern set out to test whether microbes in soils could, indeed, break down polyphenols in oxygen-free conditions.

Their controlled laboratory experiments, bolstered by a bevy of experts who helped them analyze what they were seeing, showed they were right.

Chemical maze

Wrighton and McGivern teamed up with soil polyphenolic expert Ann Hagerman of Miami University in Ohio to tackle the problem. Collaborators at the Department of Energy's Joint Genome Institute performed metagenomic sequencing of the CSU team's soil microbiome, giving the team a snapshot of every gene found in the microbial community. Other collaborators at the DOE Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory performed metaproteomics, which provided information about which proteins were being expressed by which genes in the samples.

The research team, with critical contributions by Trent Northen at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Malak Tfaily at University of Arizona, drilled down even further with three types of high-resolution, metabolite-identifying chemistry, all with the goal of showing how the large, complex polyphenol compounds were being pulled apart by microbes into their small-molecule components. And they had to keep straight which molecules originated from the organic polymers and which were background noise from the soil matrix.

"It was just this chemical maze, tracking these compounds," Wrighton said.

Next steps: permafrost

Now that the team has shown, in a lab setting, that polyphenols are food sources for soil microbes in oxygen-free zones, the next logical step is to show the same behavior in a field setting. The team was recently awarded a grant to test their theories within a permafrost system in Sweden, along with another team of collaborators. Many believe thawing permafrost holds the greatest potential for greenhouse gas reductions via carbon lockdowns, so understanding how such soil systems work is critical, according to Wrighton and McGivern.

But first, McGivern will work on building a computational infrastructure that better categorizes and identifies the different enzymes associated with microbial polyphenolic metabolisms - information that's not widely available in public databases.

"My next project is basically building a polyphenol module to insert into an existing annotation infrastructure in our lab, so that if anybody goes in and annotates their genome, they'll start to see polyphenol metabolisms," McGivern said.

And the test case she's going to use to build that system? The human gut microbiome.

INFORMATION:

Link to paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-22765-1

Los Angeles (June 8, 2021) --

IBDs, including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, are chronic conditions that occur when the intestinal immune system becomes overreactive, causing chronic diarrhea and other digestive symptoms. In a published survey at the beginning of COVID-19 vaccine distribution, 70% of IBD patients reported concern about side effects from the vaccines.

"What we've learned is that if you have IBD, the side effects you're likely to experience after a vaccine are no different than they would be for anyone else," said Gil Melmed, MD, corresponding author of the study and director of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Research at Cedars-Sinai. "If ...

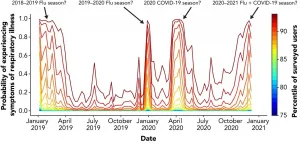

Real-world data from Sleep Number® smart bed sleepers shows a potential model for predicting and tracking COVID-19 infection using sleep and biometric measures.

Analysis of 18.2 million 360 smart bed sleep sessions finds heart rate variability differs with age, gender and day of the week.

MINNEAPOLIS, MN -- June 9, 2021 -- Today, END ...

Deaths from suicide are rising in the United States. These rising trends are especially alarming because global trends in suicide are on a downward trajectory. Moreover, in the U.S., the major mode of suicide among young Americans is by firearms.

Researchers from Florida Atlantic University's Schmidt College of Medicine and collaborators explored trends in suicide by firearms in young white and black Americans (ages 5 to 24 years) from 1999 to 2018. Results, published in the journal Annals of Public Health and Research, showed that between 2008 and 2018, rates of suicide by firearms quadrupled in young Americans ages 5 to 14 ...

Chemical rings of carbon and hydrogen atoms curve to form relatively stable structures capable of conducting electricity and more -- but how do these curved systems change when new components are introduced? Researchers based in Japan found that, with just a few sub-atomic additions, the properties can pivot to vary system states and behaviors, as demonstrated through a new synthesized chemical compound.

The results were published on April 26 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

"In the past decade, open-shell molecules have attracted considerable attention not only in the field of reactive intermediates, but also in materials science," said paper author Manabu Abe, ...

In the first three quarters of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a 30% fall in electronic and electrical equipment sales in low- and middle-income countries but only a 5% decline in high-income countries, highlighting and intensifying the digital divide between north and south, according to a new UN report.

Worldwide, sales of heavy electric appliances like refrigerators, washing machines and ovens fell the hardest -- 6-8% -- while small IT and telecommunications equipment decreased by only 1.4%. Within the latter category, sales of laptops, cell phones and gaming equipment rose in high-income countries and on a global basis, but fell in low- and middle-income ...

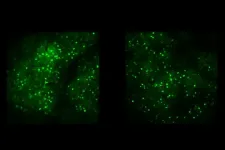

To focus on what's new, we disregard what's not. A new study by researchers at MIT's Picower Institute for Learning and Memory substantially advances understanding of how a mammalian brain enables this "visual recognition memory."

Dismissing the things in a scene that have proven to be of no consequence is an essential function because it allows animals and people to quickly recognize the new things that need to be assessed, said Mark Bear, Picower Professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and senior author of the study in the Journal of Neuroscience.

"Everyone's appropriate behavioral response to an unexpected stimulus is to devote attentional resources to that," Bear said. "Maybe it means danger. Maybe it means food. But if you learn that this once-novel ...

For the first time, Australian scientists have confirmed a link between the role of regular fish oil to break down the ability of 'superbugs' to become resistant to antibiotics.

The discovery, led by Flinders University and just published in international journal mBio, found that the antimicrobial powers of fish oil fatty acids could prove a simple and safe dietary supplement for people to take with antibiotics to make their fight against infection more effective.

"Importantly, our studies indicate that a major antibiotic resistance mechanism in cells can be negatively impacted by the uptake of omega-3 dietary lipids," says microbiologist Dr Bart Eijkelkamp, who leads the Bacterial Host Adaptation Research Lab at ...

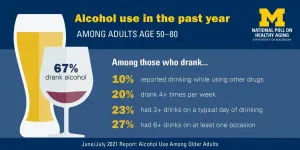

As many older adults get back to normal life across the United States thanks to high rates of vaccination and lower COVID-19 activity, a new poll suggests many should watch their alcohol intake.

In all, 23% of adults over 50 who drink alcohol reported that they routinely had three or more drinks in one sitting, according to END ...

DALLAS, June 9, 2021 -- Many adults with a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) continue to smoke cigarettes and/or use other tobacco products, despite knowing it increases their risk of having another cardiovascular event, according to new research published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access journal of the American Heart Association.

To understand how many adults with CVD continue to use tobacco products, investigators reviewed survey responses from the large, national Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study (PATH) to compare tobacco use rates over time. The participants of the current study included 2,615 adults (ages 18 or older) with a self-reported history of heart attack, heart failure, stroke or other heart disease, ...

The field of ultrafast nonlinear photonics has now become the focus of numerous studies, as it enables a host of applications in advanced on-chip spectroscopy and information processing. The latter in particular requires a strongly intensity-dependent optical refractive index that can modulate optical pulses faster than even picosecond timescales and on sub-millimeter scales suitable for integrated photonics.

Despite the tremendous progress made in this field, there is currently no platform providing such features for the ultraviolet (UV) spectral range, which is where broadband spectra generated by nonlinear modulation can be used for new on-chip ultrafast chemical and biochemical spectroscopy devices.

Now, an ...