(Press-News.org) A study published in the June 10, 2021 issue of Cell describes a remarkable new mechanism by which the body's own immune system can eliminate cancer cells without damaging host cells. The findings have the potential to develop first-in-class medicines that are designed to be selective for cancer cells and non-toxic to normal cells and tissues. If successful, this discovery may improve the practice of precision medicine by ensuring the right drug is delivered at the right dose at the right time.

Our immune system plays a critical role in our ability to fight off diseases while keeping us healthy. For example, the immune system has the ability to recognize and attack a wide range of infectious pathogens, including bacteria, fungi and protozoa. Researchers at the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center were interested in learning whether and how the immune system can mount a similar response against cancer.

Such a discovery could reveal cancer's weak spot, or Achilles' heel, and make it possible to develop new, more effective treatments with fewer unwanted side effects.

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), a type of white blood cell, provide a strong clue. PMNs respond to chemical signals emitted by the immune system and migrate to different sites in the body where they are needed. However, the exact mechanism by which they cause cancer cells to die is not fully understood. Through this new study, the team at UChicago identified neutrophil elastase (ELANE) as a major anti-cancer protein released by human neutrophils that activates cell death pathways specifically in cancer cells. ELANE causes cancer cells to die in both tumors and distant locations where they have spread, while sparing nearby healthy cells.

"Taking a step back, what I think we've stumbled upon is our body's first response to mutated cells," said Lev Becker, PhD, lead author on the paper and associate professor in the Ben May Department for Cancer Research at UChicago. "Cells are constantly changing and mutations accumulate. Some people develop cancer, others do not. The pathway that we've discovered may help explain the primordial mechanisms of our immune system to eliminate those mutated cells."

Using human and mouse models, Becker and colleagues observed that ELANE starts a complex cancer-killing program that suppresses cell survival pathways, induces DNA damage, elevates mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production, and ultimately activates programmed cell death, known as apoptosis.

This chain of events is triggered by PMNs secreting an enzyme called elastase, which breaks down proteins into smaller molecules. As a result, this process liberates the CD95 death domain, a system responsible for keeping the immune system in balance by controlling which cells undergo apoptosis. The activated CD95 death domain then interacts with histone H1, which are elevated in cancer cells to maintain their genomic stability.

ELANE consistently activated this program in many types of cancer cell lines but not in any non-cancer cells tested. According to the researchers, ELANE's specificity for cancer versus non-cancer cells may limit potential toxicity, a possibility that is strengthened by the lack of side effects observed in tumor-free mice injected with ELANE. This selective killing also preserves immune cells, allowing them to capitalize on liberated antigens and generate a boosted immune response that extends to sites where cancer has spread.

Because it can kill a wide range of cancer cells, the treatment may be able to work whatever the cancer's genetic make-up. The researchers demonstrated ELANE's efficacy across nine types of genetically diverse cancer--including difficult-to-treat cancers such as triple-negative breast cancer, melanoma, and lung cancer.

In addition to the discoveries described above, the researchers reported that they uncovered differences between human and mouse neutrophils in releasing active ELANE and showed that porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE), a protein similar to ELANE that is less sensitive to tumor inhibitors, induces an even better therapeutic response.

The researchers said that future studies are warranted to learn how to maximize the therapeutic effects of ELANE/PPE, both as a single therapy and in combination with other cancer treatments.

"This is one of those findings where if we had gone the traditional route of starting in mice we would have never found it," said Becker. "In this instance, we began with observations from patients, brought it back to the lab to study further in mice, and we are hopeful we'll be able to bring it back to humans as a novel cancer treatment."

The unique approach to cancer treatment may be translated to real-world applications. Onchilles Pharma, for which Becker serves as the scientific founder and director, recently received Series A financial backing from investors to advance the first drug candidate based on his work in preclinical proof-of-concept studies.

INFORMATION:

The study, "Neutrophil elastase selectively kills cancer cells and attenuates tumorigenesis" was funded by the Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center Janet D. Rowley Discovery Fund, University of Chicago Cancer Research Foundation J. Clifford Moos Award, Ruth Bruch Triple Negative Breast Cancer Research Award, and Women's Board Faculty

Research Startup Funds and Ben May Department Startup Funds.

Additional authors include Chang Cui, Kasturi Chakraborty, Xu Anna Tang, Guolin Zhou, Kelly Q. Schoenfelt, Kristen M. Becker, Alexandria Hoffman, Ya-Fang Chang, Ariane Blank, Catherine A. Reardon, Hilary A. Kenny, Ernst Lengyel, Geoffrey Greene of UChicago; and Tomas Vaisar of the University of Washington, Seattle.

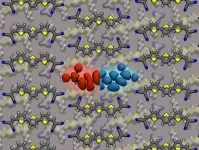

Organic semiconductors have earned a reputation as energy efficient materials in organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs) that are employed in large area displays. In these and in other applications, such as solar cells, a key parameter is the energy gap between electronic states. It determines the wavelength of the light that is emitted or absorbed. The continuous adjustability of this energy gap is desirable. Indeed, for inorganic materials an appropriate method already exists - the so-called blending. It is based on engineering the band gap by substituting atoms in the material. This allows for a continuous tunability as, for example in aluminum gallium arsenide semiconductors. Unfortunately, this is not transferable to organic semiconductors ...

Leipzig. Soot particles from oil and wood heating systems as well as road traffic can pollute the air in Europe on a much larger scale than previously assumed. This is what researchers from the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS) conclude from a measurement campaign in the Thuringian Forest in Germany. The evaluation of the sources showed that about half of the soot particles came from the surrounding area and the other half from long distances. From the researchers' point of view, this underlines the need to further reduce emissions of soot that ...

It is generally agreed that sperms "swim" by beating or rotating their soft tails. However, a research team led by scientists from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) has discovered that ray sperms move by rotating both the tail and the head. The team further investigated the motion pattern and demonstrated it with a robot. Their study has expanded the knowledge on the microorganisms' motion and provided inspiration for robot engineering design.

The research is co-led by Dr Shen Yajing, Associate Professor from CityU's Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME), and Dr Shi Jiahai, Assistant Professor of the Department of Biomedical Sciences (BMS). Their findings have been published in ...

An electrode coating just one molecule thick can significantly enhance the performance of an organic photovoltaic cell, KAUST researchers have found. The coating outperforms the leading material currently used for this task and may pave the way for improvements in other devices that rely on organic molecules, such as light-emitting diodes and photodetectors.

Unlike the most common photovoltaic cells that use crystalline silicon to harvest light, organic photovoltaic cells (OPVs) rely on a light-absorbing layer of carbon-based molecules. Although OPVs cannot yet rival the performance of silicon cells, they could be easier and cheaper to manufacture at a very large scale using ...

The type of material present under glaciers has a big impact on how fast they slide towards the ocean. Scientists face a challenging task to acquire data of this under-ice landscape, let alone how to represent it accurately in models of future sea-level rise.

"Choosing the wrong equations for the under-ice landscape can have the same effect on the predicted contribution to sea-level rise as a warming of several degrees", says Henning Åkesson, who led a new published study on Petermann Glacier in Greenland.

Glaciers and ice sheets around the world currently lose more than 700,000 Olympic swimming pools of water every day. Glaciers form by the transformation of snow into ice, which is later melted by ...

With the start of the United Nations' Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, which runs through 2030, a tremendous amount of money and effort will be put into re-growing forests, making over-exploited farmland productive, and reviving damaged marine environments. This is a good, and vital, initiative. Without quick action to clean up the fallout of humanity's scorched-earth economic systems, goals on hunger, biodiversity and climate will be unattainable.

But in examining restoration projects already underway across the globe, a group of scientists has found that restoration action is at risk of failure if it doesn't make ...

Palaeoclimatologists study climate of the geological past. Using an innovative technique, new research by an international research team led by Niels de Winter (VUB-AMGC & Utrecht University) shows for the first time that dinosaurs had to deal with greater seasonal differences than previously thought.

De Winter: "We used to think that when the climate warmed like it did in the Cretaceous period, the time of the dinosaurs, the difference between the seasons would decrease, much like the present-day tropics experience less temperature difference between ...

Inaccessible workplaces, normative departmental cultures and 'ableist' academic systems have all contributed to the continued underrepresentation and exclusion of disabled researchers in the Geosciences, according to an article published today (Thursday 8 June) in Nature Geosciences.

The article argues that changes to both working spaces and attitudes are urgently needed if institutions are to attract, safeguard and retain people with disabilities.

Anya Lawrence, a disabled early career researcher in the University of Birmingham's School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Science and author of the piece says:

"Disabled geoscientists like myself face barrier after barrier on a daily ...

People who smoke, suffer from high blood pressure, obesity, or diabetes are not only at greater risk of suffering a stroke, heart attack, or dementia. For them, the risk of being affected by depressive mood or depression also increases. The more risk factors a person has, the more likely this is. Until now, however, it was unclear whether this probability also depends on their age. Earlier studies had already shown for other diseases such as dementia or stroke that a combination of several risk factors leads to a more frequent onset of the disease between the ages of 40 and 65 than in old age. Until now, however, it was unclear whether this also applies to depression.

Researchers ...

MORGANTOWN, W. Va.-- Joining a club that sparks a new interest, playing a new intramural sport or finding a new group of friends may be just as indicative of a college freshman's loss of self-control as drinking or drug use, according to new research at West Virginia University.

Self-control--the ability to exercise personal restraint, inhibit impulsivity and make purposeful decisions--in that first year partly depends on a student's willingness to try new things, including things adults would call "good."

That's a new finding, according to Kristin Moilanen, associate professor of child development and family studies. The study, "Predictors of initial status and change in self-control during the college transition," observed 569 first year ...