(Press-News.org) When lithium ions flow in and out of a battery electrode during charging and discharging, a tiny bit of oxygen seeps out and the battery's voltage - a measure of how much energy it delivers - fades an equally tiny bit. The losses mount over time, and can eventually sap the battery's energy storage capacity by 10-15%.

Now researchers have measured this super-slow process with unprecedented detail, showing how the holes, or vacancies, left by escaping oxygen atoms change the electrode's structure and chemistry and gradually reduce how much energy it can store.

The results contradict some of the assumptions scientists had made about this process and could suggest new ways of engineering electrodes to prevent it.

The research team from the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University described their work in Nature Energy today.

"We were able to measure a very tiny degree of oxygen trickling out, ever so slowly, over hundreds of cycles," said Peter Csernica, a Stanford PhD student who worked on the experiments with Associate Professor Will Chueh. "The fact that it's so slow is also what made it hard to detect."

A two-way rocking chair

Lithium-ion batteries work like a rocking chair, moving lithium ions back and forth between two electrodes that temporarily store charge. Ideally, those ions are the only things moving in and out of the billions of nanoparticles that make up each electrode. But researchers have known for some time that oxygen atoms leak out of the particles as lithium moves back and forth. The details have been hard to pin down because the signals from these leaks are too small to measure directly.

"The total amount of oxygen leakage, over 500 cycles of battery charging and discharging, is 6%," Csernica said. "That's not such a small number, but if you try to measure the amount of oxygen that comes out during each cycle, it's about one one-hundredth of a percent."

In this study, researchers measured the leakage indirectly instead, by looking at how oxygen loss modifies the chemistry and structure of the particles. They tracked the process at several length scales - from the tiniest nanoparticles to clumps of nanoparticles to the full thickness of an electrode.

Because it's so difficult for oxygen atoms to move around in solid materials at the temperatures where batteries operate, the conventional wisdom has been that the oxygen leaks come only from the surfaces of nanoparticles, Chueh said, although this has been up for debate.

To get a closer look at what's happening, the research team cycled batteries for different amounts of time, took them apart, and sliced the electrode nanoparticles for detailed examination at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory's Advanced Light Source. There, a specialized X-ray microscope scanned across the samples, making high-res images and probing the chemical makeup of each tiny spot. This information was combined with a computational technique called ptychography to reveal nanoscale details, measured in billionths of a meter.

Meanwhile, at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Light Source, the team shot X-rays through entire electrodes to confirm that what they were seeing at the nanoscale level was also true at a much larger scale.

A burst, then a trickle

Comparing the experimental results with computer models of how oxygen loss might occur, the team concluded that an initial burst of oxygen escapes from the surfaces of particles, followed by a very slow trickle from the interior. Where nanoparticles glommed together to form larger clumps, those near the center of the clump lost less oxygen than those near the surface.

Another important question, Chueh said, is how the loss of oxygen atoms affects the material they left behind. "That's actually a big mystery," he said. "Imagine the atoms in the nanoparticles are like close-packed spheres. If you keep taking oxygen atoms out, the whole thing could crash down and densify, because the structure likes to stay closely packed."

Since this aspect of the electrode's structure could not be directly imaged, the scientists again compared other types of experimental observations against computer models of various oxygen loss scenarios. The results indicated that the vacancies do persist - the material does not crash down and densify - and suggest how they contribute to the battery's gradual decline.

"When oxygen leaves, surrounding manganese, nickel and cobalt atoms migrate. All the atoms are dancing out of their ideal positions," Chueh said. "This rearrangement of metal ions, along with chemical changes caused by the missing oxygen, degrades the voltage and efficiency of the battery over time. People have known aspects of this phenomenon for a long time, but the mechanism was unclear."

Now, he said, "we have this scientific, bottom-up understanding" of this important source of battery degradation, which could lead to new ways of mitigating oxygen loss and its damaging effects.

INFORMATION:

Chueh is an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC. The Advanced Light Source, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and Spallation Neutron Source at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, where parts of this work were performed, are DOE Office of Science user facilities. Major funding came from the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Vehicle Technologies Office, and samples were provided by the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology Global Research Outreach program.

Citation: Peter M. Csernica et al., Nature Energy, 14 June 2021 (10.1038/s41560-021-00832-7)

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

MISSOULA - Those in love with the outdoors can spend their entire lives chasing that perfect campsite. New University of Montana research suggests what they are trying to find.

Will Rice, a UM assistant professor of outdoor recreation and wildland management, used big data to study the 179 extremely popular campsites of Watchman Campground in Utah's Zion National Park. Campers use an online system to reserve a wide variety of sites with different amenities, and people book the sites an average of 51 to 142 days in advance, providing hard data about demand.

Along with colleague Soyoung Park of Florida Atlantic University, Rice sifted through nearly 23,000 reservations. The researchers found that price and availability of electricity were the largest drivers of demand. Proximity ...

Albeit very small, with a carapace width of only 3 cm, the Atlantic mangrove fiddler crab Leptuca thayeri can be a great help to scientists seeking to understand more about the effects of global climate change. In a study published in the journal Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, Brazilian researchers supported by São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP show how the ocean warming and acidification forecast by the end of the century could affect the lifecycle of these crustaceans.

Embryos of L. thayeri were exposed to a temperature rise of 4 °C and a pH reduction of 0.7 against the average for their habitat, growing faster as a result. However, a larger number of ...

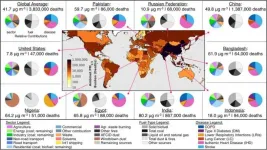

An interdisciplinary group of researchers from across the globe has comprehensively examined the sources and health effects of air pollution -- not just on a global scale, but also individually for more than 200 countries.

They found that worldwide, more than one million deaths were attributable to the burning of fossil fuels in 2017. More than half of those deaths were attributable to coal.

Findings and access to their data, which have been made public, were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Pollution is at once a global crisis and a devastatingly personal problem. It is analyzed by satellites, but PM2.5 -- tiny particles that can infiltrate a person's lungs -- can also sicken a person who cooks dinner nightly on a cookstove.

"PM2.5 ...

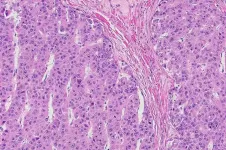

Treatment options for a deadly liver cancer, fibrolamellar carcinoma, are severely lacking. Drugs that work on other liver cancers are not effective, and although progress has been made in identifying the specific genes involved in driving the growth of fibrolamellar tumors, these findings have yet to translate into any treatment. For now, surgery is the only option for those affected--mostly children and young adults with no prior liver conditions.

Sanford M. Simon and his group understood that patients dying of fibrolamellar could not afford to wait. "There are people who need therapy now," he says. So his group threw the kitchen sink at the problem and tested over 5,000 compounds, either already approved for other clinical uses or in clinical ...

DALLAS - June 14, 2021 - Overweight cancer patients receiving immunotherapy treatments live more than twice as long as lighter patients, but only when dosing is weight-based, according to a study by cancer researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

The findings, published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, run counter to current practice trends, which favor fixed dosing, in which patients are given the same dose regardless of weight. The study included data on nearly 300 patients with melanoma, lung, kidney, and head and neck cancers ...

Leesburg, VA, June 14, 2021--According to ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), high-dose intranodal lymphangiography (INL) with ethiodized oil is a safe and effective procedure for treating high-output postsurgical chylothorax with chest tube removal in 83% of patients.

"To our knowledge," wrote corresponding author Geert Maleux of University Hospitals in Leuven, Belgium, "no data are available on the safety or potential beneficial effect of injecting higher doses of ethiodized oil to treat patients with refractory postoperative chylothorax."

All 18 patients (mean, 67 years; range, ...

A team of scientists from Kaunas University of Technology and Lithuanian Energy Institute proposed a method to convert lint-microfibers found in clothes dryers into energy. They not only constructed a pilot pyrolysis plant but also developed a mathematical model to calculate possible economic and environmental outcomes of the technology. Researchers estimate that by converting lint microfibers produced by 1 million people, almost 14 tons of oil, 21.5 tons of gas and nearly 10 tons of char could be produced.

Each year, the global population consumes approximately 80 billion pieces of clothing and approximately €140 million worth of it goes into landfill. This is accompanied by large amounts of emissions, causing serious environmental and health problems. One of the ways to lessen ...

A new study found higher education students are more engaged and motivated when they are taught using playful pedagogy rather than the traditional lecture-based method. The study was conducted by University of Colorado Denver counseling researcher Lisa Forbes and was published in the Journal of Teaching and Learning.

While many educators in higher education believe play is a method that is solely used for elementary education, Forbes argues that play is important in post-secondary education to enhance student learning outcomes.

Throughout the spring 2020 semester, Forbes observed students who were enrolled in three of her courses between the ages of 23-43. To introduce playful pedagogy, Forbes included games and play, not always tied to the ...

Solar flares jetting out from the sun and thunderstorms generated on Earth impact the planet's ionosphere in different ways, which have implications for the ability to conduct long range communications.

A team of researchers working with data collected by the Incoherent Scatter Radar (ISR) at the Arecibo Observatory, satellites, and lightning detectors in Puerto Rico have for the first time examined the simultaneous impacts of thunderstorms and solar flares on the ionospheric D-region (often referred to as the edge of space).

In the first of its kind analysis, the team determined that solar flares ...

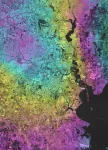

The types of land around us play an important role in how major storms will unfold -- flood waters may travel differently over rural versus urban areas, for example. However, it's challenging to get an accurate picture of land types using only satellite image data because it is so difficult to interpret.

Researchers at the Cockrell School of Engineering have, for the first time, applied a machine learning algorithm to measure the surface roughness of different types of land with a high level of detail. The team used a type of satellite imagery that is more dependable and easier to capture than typical optical photographs but also more challenging to analyze. And they are working to integrate this data into storm surge models to give a clearer ...