(Press-News.org) It is possible to re-create a bird's song by reading only its brain activity, shows a first proof-of-concept study from the University of California San Diego. The researchers were able to reproduce the songbird's complex vocalizations down to the pitch, volume and timbre of the original.

Published June 16 in Current Biology, the study lays the foundation for building vocal prostheses for individuals who have lost the ability to speak.

"The current state of the art in communication prosthetics is implantable devices that allow you to generate textual output, writing up to 20 words per minute," said senior author Timothy Gentner, a professor of psychology and neurobiology at UC San Diego. "Now imagine a vocal prosthesis that enables you to communicate naturally with speech, saying out loud what you're thinking nearly as you're thinking it. That is our ultimate goal, and it is the next frontier in functional recovery."

The approach that Gentner and colleagues are using involves songbirds such as the zebra finch. The connection to vocal prostheses for humans might not be obvious, but in fact, a songbird's vocalizations are similar to human speech in various ways. They are complex, and they are learned behaviors.

"In many people's minds, going from a songbird model to a system that will eventually go into humans is a pretty big evolutionary jump," said Vikash Gilja, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at UC San Diego who is a co-author on the study. "But it's a model that gives us a complex behavior that we don't have access to in typical primate models that are commonly used for neural prosthesis research."

The research is a cross-collaborative effort between engineers and neuroscientists at UC San Diego, with the Gilja and Gentner labs working together to develop neural recording technologies and neural decoding strategies that leverage both teams' expertise in neurobiological and behavioral experiments.

The team implanted silicon electrodes in male adult zebra finches and monitored the birds' neural activity while they sang. Specifically, they recorded the electrical activity of multiple populations of neurons in the sensorimotor part of the brain that ultimately controls the muscles responsible for singing.

The researchers fed the neural recordings into machine learning algorithms. The idea was that these algorithms would be able to make computer-generated copies of actual zebra finch songs just based on the birds' neural activity. But translating patterns of neural activity into patterns of sounds is no easy task.

"There are just too many neural patterns and too many sound patterns to ever find a single solution for how to directly map one signal onto the other," said Gentner.

To accomplish this feat, the team used simple representations of the birds' vocalization patterns. These are essentially mathematical equations modeling the physical changes--that is, changes in pressure and tension--that happen in the finches' vocal organ, called a syrinx, when they sing. The researchers then trained their algorithms to map neural activity directly to these representations.

This approach, the researchers said, is more efficient than having to map neural activity to the actual songs themselves.

"If you need to model every little nuance, every little detail of the underlying sound, then the mapping problem becomes a lot more challenging," said Gilja. "By having this simple representation of the songbirds' complex vocal behavior, our system can learn mappings that are more robust and more generalizable to a wider range of conditions and behaviors."

The team's next step is to demonstrate that their system can reconstruct birdsong from neural activity in real time.

Part of the challenge is that songbirds' vocal production, like humans', involves not just output of the sound but a constant monitoring of the environment and constant monitoring of the feedback. If you put headphones on humans, for example, and delay when they hear their own voice, disrupting just the temporal feedback, they'll start to stutter. Birds do the same thing. They're listening to their own song. They make adjustments based on what they just heard themselves singing and what they hope to sing next, Gentner explained. A successful vocal prosthesis will ultimately need to work on a timescale that is similarly fast and also intricate enough to accommodate the entire feedback loop, including making adjustments for errors.

"With our collaboration," said Gentner, "we are leveraging 40 years of research in birds to build a speech prosthesis for humans--a device that would not simply convert a person's brain signals into a rudimentary set of whole words but give them the ability to make any sound, and so any word, they can imagine, freeing them to communicate whatever they wish."

INFORMATION:

Paper: "Neurally driven synthesis of learned, complex vocalizations." Co-authors include Ezequiel M. Arneodo, Shukai Chen and Daril E. Brown, all at UC San Diego.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01DC018446), the Kavli Institute for the Brain and Mind (IRG no. 2016-004), the Office of Naval Research (MURI N00014-13-1-0205) and a Pew Latin American Fellowship in the Biomedical Sciences.

Declaration of interests: Vikash Gilja is a compensated consultant of Paradromics, Inc., a brain-computer interface company.

When Betelgeuse, a bright orange star in the constellation of Orion, became visibly darker in late 2019 and early 2020, the astronomy community was puzzled. A team of astronomers have now published new images of the star's surface, taken using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (ESO's VLT), that clearly show how its brightness changed. The new research reveals that the star was partially concealed by a cloud of dust, a discovery that solves the mystery of the "Great Dimming" of Betelgeuse.

Betelgeuse's dip in brightness -- a change noticeable even to the ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined to what extent cannabis use is associated with thickness in brain areas measured by magnetic resonance imaging in a study of adolescents.

Authors: Matthew D. Albaugh, Ph.D., of the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine in Burlington, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1258)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The ...

What The Study Did: Survival among people with early-onset (diagnosed before age 50) colorectal cancer compared with later-onset colorectal cancer (diagnosed at ages 51 through 55) was compared using data from the National Cancer Database.

Authors: Charles S. Fuchs, M.D., M.P.H., of the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven, Connecticut, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12539)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and ...

What The Study Did: This study demonstrated an association between receiving the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccine and a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers beginning eight days after the first dose.

Authors: Michael E. Charness, M.D., of the VA Boston Healthcare System in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16416)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest ...

A ball of 4,000-year-old hair frozen in time tangled around a whalebone comb led to the first ever reconstruction of an ancient human genome just over a decade ago.

The hair, which was preserved in arctic permafrost in Greenland, was collected in the 1980s and stored at a museum in Denmark. It wasn't until 2010 that evolutionary biologist Professor Eske Willerslev was able to use pioneering shotgun DNA sequencing to reconstruct the genetic history of the hair.

He found it came from a man from the earliest known people to settle in Greenland ...

Stimulation of the nervous system with neurotechnology has opened up new avenues for treating human disorders, such as prosthetic arms and legs that restore the sense of touch in amputees, prosthetic fingertips that provide detailed sensory feedback with varying touch resolution, and intraneural stimulation to help the blind by giving sensations of sight.

Scientists in a European collaboration have shown that optic nerve stimulation is a promising neurotechnology to help the blind, with the constraint that current technology has the capacity of providing only simple visual signals.

Nevertheless, the scientists' vision (no pun intended) is to design these simple visual signals to be meaningful in assisting the blind with daily living. Optic nerve stimulation ...

Although plexiglass barriers are seemingly everywhere these days -- between grocery store lanes, around restaurant tables and towering above office cubicles -- they are an imperfect solution to blocking virus transmission.

Instead of capturing virus-laden respiratory droplets and aerosols, plexiglass dividers merely deflect droplets, causing them to bounce away but remain in the air. To enhance the function of these protective barriers, Northwestern University researchers have developed a new transparent material that can capture droplets and aerosols, effectively ...

New York, NY (June 16, 2021) -- Immune cells that normally repair tissues in the body can be fooled by tumors when cancer starts forming in the lungs and instead help the tumor become invasive, according to a surprising discovery reported by Mount Sinai scientists in Nature in June.

The researchers found that early-stage lung cancer tumors coopt the immune cells, known as tissue-resident macrophages, to help invade lung tissue. They also mapped out the process, or program, of how the macrophages allows a tumor to hurt the tissues the macrophage normally repairs. This process allows the tumor to hide from the immune system and proliferate into later, deadly stages of cancer.

Macrophages play a key ...

June 16, 2021, CLEVELAND: New findings from Cleveland Clinic researchers show for the first time that the gut microbiome impacts stroke severity and functional impairment following stroke. The results, published in Cell Host & Microbe, lay the groundwork for potential new interventions to help treat or prevent stroke.

The research was led by Weifei Zhu, Ph.D., and Stanley Hazen, M.D., Ph.D., of Cleveland Clinic's Lerner Research Institute. The study builds on more than a decade of research spearheaded by Dr. Hazen and his team related to the gut microbiome's role in cardiovascular health and disease, including the adverse effects of TMAO (trimethylamine N-oxide) - a byproduct produced when gut bacteria digest certain nutrients abundant in red meat and other animal ...

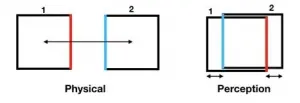

Our eyes move three times per second. Every time we move our eyes, the world in front of us flies across the retina at the back of our eyes, dramatically shifting the image the eyes send to the brain; yet, as far as we can tell, nothing appears to move. A new study provides new insight into this process known as "visual stabilization". The results are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Our results show that a framing strategy is at work behind the scenes all the time, which helps stabilize our visual experience," says senior author Patrick Cavanagh, a research professor in psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth ...