(Press-News.org) When a University of Michigan-led research team reported last year that North American migratory birds have been getting smaller over the past four decades and that their wings have gotten a bit longer, the scientists wondered if they were seeing the fingerprint of earlier spring migrations.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that birds are migrating earlier in the spring as the world warms. Perhaps the evolutionary pressure to migrate faster and arrive at breeding grounds earlier led to the physical changes the U-M-led team observed.

"We know that bird morphology has a major effect on the efficiency and speed of flight, so we became curious whether the environmental pressure to advance spring migration would lead to natural selection for longer wings," said U-M evolutionary biologist Marketa Zimova.

In a new study scheduled for publication June 21 in the Journal of Animal Ecology, Zimova and her colleagues test for a link between the observed morphological changes and earlier spring migration, which is an example of timing shifts biologists call phenological changes.

Unexpectedly, they found that the morphological and phenological changes are happening in parallel but appear to be unrelated or "decoupled."

"We found that birds are changing in size and shape independently of changes in their migration timing, which was surprising," said Zimova, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the U-M Institute for Global Change Biology.

Both the new study and the 2020 paper that described the changes in body size and wing length were based on analyses of some 70,000 bird specimens from 52 species at the Field Museum. The birds were collected after colliding with Chicago buildings during spring and fall migrations between 1978 and 2016.

In addition to its finding about the decoupling of morphological and phenological changes, the new study is believed to be the first to use museum specimens from building collisions to examine long-term trends in bird migration timing. Several previous reports relied on data from bird-banding studies or, more recently, the analysis of weather radar records.

The U-M-led team confirmed previous findings about earlier spring migration and provided new insights about fall bird migrations in North America, which have been less studied. Specifically, they found that the earliest spring migrants are now arriving nearly five days sooner than they did four decades ago, while the earliest fall migrants are heading south about 10 days earlier than they used to.

Notably, the last fall stragglers now depart about a week later than they used to so that, overall, the duration of the fall migration season has been stretched considerably.

"It is unusual to have a dataset that can provide insights into multiple aspects of global change--such as phenology and morphology--at the same time," said U-M evolutionary biologist and ornithologist Ben Winger, a senior author of the study.

"I was impressed that the collision data so clearly showed evidence of advancing spring migration. The collision monitors in Chicago have been collecting these data on bird building collisions for 40 years and, meanwhile, the birds have been changing the timing of their migratory patterns in ways that were imperceptible until the dataset as a whole was examined," said Winger, an assistant professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and an assistant curator at the Museum of Zoology.

Last year in the journal Ecology Letters, the U-M-led team reported that nearly all of the 52 bird species in their study experienced both declines in body size and simultaneous increases in wing length over the four-decade period.

At the time, they linked the measured body-size reductions to warmer temperatures at the birds' breeding grounds. Since smaller bodies are more efficient at dissipating heat, perhaps smaller birds gained a competitive advantage and were favored by natural selection. Alternatively, the body-size reductions could be the result of a process called developmental plasticity, the ability of an individual to modify its development in response to changing environmental conditions.

The researchers also suggested that the observed increases in wing length helped compensate for the smaller body size, allowing the birds to maintain migration by increasing flight efficiency.

But the previous study did not test to see whether the changes in body size and wing length were driven by climate-related shifts in migration timing. In the new study, they tested for that link.

For each of the 52 species, the researchers estimated temporal trends in morphology and changes in the timing of migration. Then they tested for associations between species-specific rates of phenological and morphological change, taking into account the potential effects of migratory distance and breeding latitude.

They found no evidence that rates of phenological change across years, or migratory distance and breeding latitude, are predictive of rates of concurrent changes in morphological traits.

"Scientifically, this is really the most interesting and novel finding," said U-M evolutionary biologist and ornithologist Brian Weeks, a senior author of the new Journal of Animal Ecology study.

Advances in phenology, such as flowering plants blooming earlier in the spring, and changes in morphology, including body size reductions, are among the most commonly described biological responses to global warming temperatures.

Many studies of plant and animal adaptive responses to climate warming have looked at either phenological or morphological changes, but few have been able to examine both at the same time. The depth of the Field Museum dataset enabled the U-M-led team to examine multiple responses to climate warming simultaneously and to test for connections between them.

"It is often assumed that morphological changes driven by climate and changes in the timing of migration must interact to either facilitate or constrain adaptive responses to climate change," said Weeks, an assistant professor at the School for Environment and Sustainability. "But this has never to my knowledge been tested empirically at a significant scale, until now, due to lack of data."

So, if increased wing length is not responsible for the earlier arrival of migratory birds in Chicago each spring, then what is? Previous studies suggest that shorter, less frequent stopovers during the northbound trek may be a factor.

"And there might be other adjustments that allow birds to migrate faster that we haven't thought about--maybe some physiological adaptation that might allow faster flight without causing the birds to overheat and lose too much water," Zimova said.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Zimova, Weeks and Winger, the other author of the Journal of Animal Ecology study is David Willard of the Field Museum, the ornithologist and collections manager emeritus who measured all 70,716 birds analyzed in the study. The Field Museum dataset has been a bonanza for bird researchers and has led to several recent publications.

The newly reported study was supported by U-M's Institute for Global Change Biology at the School for Environment and Sustainability.

Photos: END

University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers identified a new gene that may be linked to certain neurodevelopmental disorders and intellectual disabilities. The researchers believe that finding genes involved in certain types of developmental disorders, provide an important first step in determining the cause of these disorders and ultimately in developing potential therapies for treating them. The paper was recently published in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

About 3 percent of the world's population has intellectual disability. Up to half the cases are due to genetics, however, because many thousands of genes contribute to brain development, it has been difficult to identify the specific cause for each patient.

Once the researchers ...

People who struggle with social anxiety might experience increased distress related to mask-wearing during and even after the COVID-19 pandemic.

A paper authored by researchers from the University of Waterloo's Department of Psychology and Centre for Mental Health Research and Treatment also has implications for those who haven't necessarily suffered from social anxiety in the past.

"The adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health outcomes, including anxiety and depression, have been well-documented," said David Moscovitch, professor of clinical psychology and co-author of the paper. "However, little is known about effects of increased mask-wearing on social interactions, social anxiety, or overall mental health.

"It is also possible ...

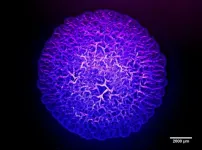

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogenic bacterium present in many ecological niches, such as plant roots, stagnant water or even the pipes of our homes. Naturally very versatile, it can cause acute and chronic infections that are potentially fatal for people with weakened immune systems. The presence of P. aeruginosa in clinical settings, where it can colonise respirators and catheters, is a serious threat. In addition, its adaptability and resistance to many antibiotics make infections by P. aeruginosa increasingly difficult to treat. There is therefore an urgent need to develop new antibacterials. Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, ...

(Vienna, Monday, 21 June, 2021) COVID-19 patients suffer from cognitive and behavioural problems two months after being discharged from hospital, a new study presented at the 7th Congress of the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) has found.

Issues with memory, spatial awareness and information processing problems were identified as possible overhangs from the virus in post-COVID-19 patients who were followed up within eight weeks.

The research also found that one in 5 patients reported post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with 16% presenting depressive symptoms. ...

The first global standards to embed health and wellbeing into the education system have been created amid a rise in mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers at the Centre for Adolescent Health at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) led the two-year project at the invitation of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The two reports, to be launched this week in Geneva, provide a benchmarking framework to support the implementation of 'health promoting schools,' which aim to equally foster health ...

Washington, DC - June 20, 2021 - Researchers from Yonsei University in South Korea have found that certain commensal bacteria that reside in the human intestine produce compounds that inhibit SARS-CoV-2. The research will be presented on June 20 at World Microbe Forum, an online meeting of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM), the Federation of European Microbiological Societies (FEMS), and several other societies that will take place online June 20-24.

Previous clinical findings have shown that some patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 have gastro-intestinal symptoms, while others showed signs of infection solely in the lungs.

"We wondered whether gut ...

Washington, D.C. - June 20, 2021 - Increased screen time among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic correlated with a rise in pandemic-related distress, according to research led by investigators at the Saint James School of Medicine on the Caribbean island nation, Saint Vincent. The increase in time spent viewing entertainment on a screen both prior to and during the pandemic was associated with a boost in anxiety scores. Students scored higher than non-students in pandemic-related distress. Surprisingly, the results showed no association of depression with screen ...

Washington, DC - June 20, 2021 - Researchers from the Miami University in Ohio have optimized a new technique that will allow scientists to evaluate how potential inhibitors work on antibiotic-resistant bacteria. This technique, called native state mass spectrometry, provides a quick way for scientists to identify the best candidates for effective clinical drugs, particularly in cases where bacteria can no longer be treated with antibiotics alone. This research will be presented at the American Society for Microbiology World Microbe Forum online conference on June 21, 2021.

Overuse of antibiotics in the last century has led to a rise in bacterial resistance, leading to many bacterial infections that are no longer treatable with current antibiotics. In the United States each year, 2.8 million ...

Washington, D.C. - June 20, 2021 - Although two SARS-CoV-2 variants are associated with higher transmission, patients with these variants show no evidence of higher viral loads in their upper respiratory tracts compared to the control group, a Johns Hopkins School of Medicine study found.

The emergence and higher transmission of the evolving variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has been concerning. The researchers investigated B.1.1.7, the variant first identified in the UK, and B.1.351, the variant first identified in South Africa, to evaluate if patients showed higher ...

(Vienna, Sunday, 20 June, 2021) Women who suffer from migraines are more likely to endure obstetric and postnatal complications, a study presented today at the 7th Congress of the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) has found.

Pregnant women with migraines had a higher risk of developing obstetric and post partum complications. Migraine pregnant women had increased risk of been admitted to high-risk departments- 6% in non-migraine pregnant women, 6.9% in migraine without aura and 8.7% in pregnant women who suffer from migraine with aura.

Pregnant migraine patients had significantly increased risk of gestational diagnosis ...