(Press-News.org) PULLMAN, Wash. - Fire can put a tropical songbird's sex life on ice.

Following habitat-destroying wildfires in Australia, researchers found that many male red-backed fairywrens failed to molt into their red-and-black ornamental plumage, making them less attractive to potential mates. They also had lowered circulating testosterone, which has been associated with their showy feathers.

For the study published in the Journal of Avian Biology, the researchers also measured the birds' fat stores and the stress hormone corticosterone but found those remained at normal levels.

"Really, it ended up all coming down to testosterone," said Jordan Boersma, Washington State University doctoral student and lead author on the study. "There's no evidence that the birds were actually stressed. Wildfire was just interfering with their normal, temporal pattern of elevating testosterone and then producing that colorful plumage."

While the findings are specific to this tropical songbird, they may have implications for other species that don special coloration for mating, Boersma added.

"It could be a good way to gauge how healthy a population is if you know their normal level of ornamentation," he said. "If you see that there are very few males undergoing that transition, then there is probably something in their environment that's not ideal."

Without the elevated testosterone, male red-backed fairywrens are not so red. Instead they have drab, brown feathers much like their female counterparts. Ornamental feathers can make them stand out to predators and cause conflict with competing males. As Boersma puts it, the flashy feathers are "costly." Their only advantage is in attracting female fairywrens.

"The females prefer to mate with a male fairywren who is prettier," Boersma said. "Testosterone is just one of the mechanisms that they use to get their ornamentation."

In an earlier study, Boersma and his colleagues showed that testosterone helps the fairywren process pigments in their diet called carotenoids to create their colorful feathers. This study adds further evidence of that connection as well as the birds' response to wildfire.

While other research has looked at how wildfire impacts long-term survival of birds and other animals, this is one of the few studies that look at how wildfire may affect the birds' physiology.

Red-backed fairywrens are used to living with periodic wildfires, and the researchers suspect that the suppression of testosterone is an evolved response. Wildfires can destroy the birds' grassland nesting habitat, so it is a signal that it might not good time to raise their young. The male birds then may inhibit or delay breeding by remaining brown and unattractive to mates.

For this study, the researchers observed and took blood samples from the fairywrens for five years at two different sites in the tropical northeast part of Queensland state in Australia. This allowed them to compare birds living at times and places that experienced wildfire with those that did not.

The male red-backed fairywrens typically wait for the monsoon season to molt into their bright colors when the rains bring more of the insects they eat out into the open. The researchers wanted to be sure it was the wildfire and not a dry season that was affecting their testosterone levels and feather color. During the study period, there was an unusually dry season, and the researchers observed minimal breeding among the birds, but yet the males were still producing ornamentation at a normal level. It was only post-fire that the many of the male birds stayed brown.

The researchers not only found that more males remained brown immediately following the wildfire event but also that the testosterone was lower in the brown males--and lower in the population at large relative to previous years without fires.

INFORMATION:

Male jackdaws don't stick around to console their mate after a traumatic experience, new research shows.

Jackdaws usually mate for life and, when breeding, females stay at the nest with eggs while males gather food.

Rival males sometimes visit the nest and attack the lone female, attempting to mate by force.

In the new study, University of Exeter researchers expected males to console their partner after these incidents by staying close and engaging in social behaviours like preening their partner's feathers.

However, males focussed on their own safety - they still brought food to the nest, but they visited less often and spent less time with the female.

"Humans often console friends or family in distress, but it's unclear whether animals do this in the wild," said Beki ...

A new analysis of 58 studies and 44305 patients published in Anaesthesia (a journal of the Association of Anaesthetists) shows that, contrary to some previous research, being male and increasing body mass index (BMI) are not associated with increased mortality in COVID-19 in patients admitted into intensive care (ICU).

However, the study, by Dr Bruce Biccard (Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa) and colleagues finds that a wide range of factors are associated with death from COVID-19 in ICU.

Patients with COVID-19 in ICU were 40% more likely to die with a history of smoking, 54% more likely with high blood pressure, 41% more likely with diabetes, ...

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, a scientific breakthrough that transformed Type 1 diabetes, once known as juvenile diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes, from a terminal disease into a manageable condition.

Today, Type 2 diabetes is 24 times more prevalent than Type 1. The rise in rates of obesity and incidence of Type 2 diabetes are related and require new approaches, according to University of Arizona researchers, who believe the liver may hold the key to innovative new treatments.

"All current therapeutics for ...

Los Angeles, Calif. - The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), the largest global HIV research network, today announced that findings from a sub-study of REPRIEVE (A5332/A5332s, an international clinical trial studying heart disease prevention in people living with HIV) have been published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open (JAMA Network Open). The study found that approximately half of study participants, who were considered by traditional measures to be at low-to-moderate risk of future heart disease, had atherosclerotic plaque in their coronary arteries.

While it is well-known that people living with HIV are at ...

(OTTAWA, ON) The University of Ottawa, the University of Montreal and the Assembly of First Nations are pleased to announce the newly published First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES) in the Canadian Journal of Public Health. Mandated by First Nations leadership across Canada through Assembly of First Nations Resolution 30 / 2007 and realized through a unique collaboration with researchers and communities, the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study is the first national study of its kind. It was led by principal investigators Dr. Laurie Chan, a professor ...

UCLA engineers have demonstrated successful integration of a novel semiconductor material into high-power computer chips to reduce heat on processors and improve their performance. The advance greatly increases energy efficiency in computers and enables heat removal beyond the best thermal-management devices currently available.

The research was led by Yongjie Hu, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. Nature Electronics recently published the finding in this article.

Computer processors have shrunk down to nanometer scales over the years, with billions of transistors sitting on a single computer chip. While the increased number of transistors helps make computers faster and more powerful, it also generates ...

Scientists and doctors at University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (UCL GOS ICH) and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) have given hope of a gene therapy cure to children with a rare degenerative brain disorder called Dopamine Transporter Deficiency Syndrome (DTDS).

The team have recreated and cured the disease using state-of-the-art laboratory and mouse models of the disease and will soon apply for a clinical trial of the therapy. Their breakthrough comes just a decade after the faulty gene causing the disease was first discovered by the lead scientist of this work.

The results, published in Science Translational Medicine, are so promising that the UK regulatory agency MHRA has advised ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: Article topics include the Great Unconformity of the

Rocky Mountain region; new Ediacara-type fossils; the southern Cascade arc

(California, USA); the European Alps and the Late Pleistocene glacial

maximum; Permian-Triassic ammonoid mass extinction; permafrost thaw; the

southern Rocky Mountains of Colorado (USA); "gargle dynamics"; invisible

gold; and alluvial fan deposits in Valles Marineris, Mars. These Geology articles are online at

https://geology.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent

.

A new kind of invisible gold in pyrite hosted in deformation-related

dislocations

Denis Fougerouse; Steven M. Reddy; Mark ...

Natural wood remains a ubiquitous building material because of its high strength-to-density ratio; trees are strong enough to grow hundreds of feet tall but remain light enough to float down a river after being logged.

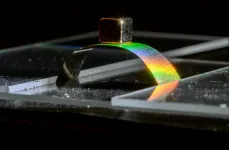

For the past three years, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania's School of Engineering and Applied Science have been developing a type of material they've dubbed "metallic wood." Their material gets its useful properties and name from a key structural feature of its natural counterpart: porosity. As a lattice of nanoscale nickel struts, metallic wood is full of regularly spaced cell-sized pores that radically decrease its density without sacrificing the material's ...

Knowing the weight of a commodity provides an objective way to value goods in the marketplace. But did a self-regulating market even exist in the Bronze Age? And what can weight systems tell us about this? A team of researchers from the University of Göttingen researched this by investigating the dissemination of weight systems throughout Western Eurasia. Their new simulation indicates that the interaction of merchants, even without substantial intervention from governments or institutions, is likely to explain the spread of Bronze Age technology to weigh goods. The results were ...